Decision-making

Academic Publications

An Inventory of Problems–29 (IOP–29) study investigating feigned schizophrenia and random responding in a British community sample

Compared to other Western countries, malingering research is still relatively scarce in the United Kingdom, partly because only a few brief and easy-to-use symptom validity tests (SVTs) have been validated for use with British test-takers. This online study examined the validity of the Inventory of Problems–29 (IOP–29) in detecting feigned schizophrenia and random responding in 151 British volunteers. Each participant took three IOP–29 test administrations: (a) responding honestly; (b) pretending to suffer from schizophrenia; and (c) responding at random. Additionally, they also responded to a schizotypy measure (O-LIFE) under standard instruction. The IOP–29’s feigning scale (FDS) showed excellent validity in discriminating honest responding from feigned schizophrenia (AUC = .99), and its classification accuracy was not significantly affected by the presence of schizotypal traits. Additionally, a recently introduced IOP–29 scale aimed at detecting random responding (RRS) demonstrated very promising results.

(From the journal abstract)

Winters, C. L., Giromini, L., Crawford, T. J., Ales, F., Viglione, D. J., & Warmelink, L. (2020). An Inventory of Problems–29 (IOP–29) study investigating feigned schizophrenia and random responding in a British community sample. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 1–20.

To freeze or not to freeze: A culture-sensitive motion capture approach to detecting deceit

We present a new signal for detecting deception: full body motion. Previous work on detecting deception from body movement has relied either on human judges or on specific gestures (such as fidgeting or gaze aversion) that are coded by humans. While this research has helped to build the foundation of the field, results are often characterized by inconsistent and contradictory findings, with small-stakes lies under lab conditions detected at rates little better than guessing. We examine whether a full body motion capture suit, which records the position, velocity, and orientation of 23 points in the subject’s body, could yield a better signal of deception. Interviewees of South Asian (n = 60) or White British culture (n = 30) were required to either tell the truth or lie about two experienced tasks while being interviewed by somebody from their own (n = 60) or different culture (n = 30). We discovered that full body motion–the sum of joint displacements–was indicative of lying 74.4% of the time. Further analyses indicated that including individual limb data in our full body motion measurements can increase its discriminatory power to 82.2%. Furthermore, movement was guilt- and penitential-related, and occurred independently of anxiety, cognitive load, and cultural background. It appears that full body motion can be an objective nonverbal indicator of deceit, showing that lying does not cause people to freeze.

(From the journal abstract)

Zee, S. van der, Poppe, R., Taylor, P. J., & Anderson, R. (2019). To freeze or not to freeze: A culture-sensitive motion capture approach to detecting deceit. PLOS ONE, 14(4), e0215000.

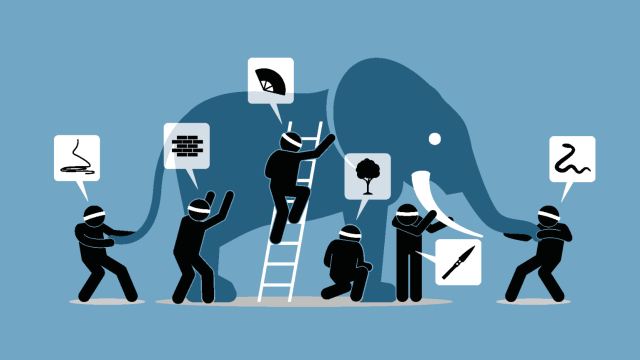

The Psychology of Criminal Investigation: From Theory to Practice

The contribution of psychological research to the prevention of miscarriages of justice and the development of effective investigative techniques is now established to a point where law enforcement agencies in numerous countries either employ psychologists as part of their staff, or work in cooperation with academic institutions. The application of psychology to investigation is particularly effective when academics and practitioners work together. This book brings together leading experts to discuss the application of psychology to criminal investigation.

This book offers an overview of models of investigation from a psychological and practical view point, covering topics such as investigative decision making, the presentation of evidence, witness testimony, the detection of deception, interviewing suspects and evidence-based police training. It is essential reading for students, researchers and practitioners engaged with police practice, investigation and forensic psychology.

(From the journal abstract)

Griffiths, A., & Milne, R. (Eds.). (2018). The Psychology of Criminal Investigation: From Theory to Practice (1st ed.). Routledge.

Terrorist Decision Making in the Context of Risk, Attack Planning, and Attack Commission

Terrorists from a wide array of ideological influences and organizational structures consider security and risk on a continuous and rational basis. The rationality of terrorism has been long noted of course but studies tended to focus on organizational reasoning behind the strategic turn toward violence. A more recent shift within the literature has examined rational behaviors that underpin the actual tactical commission of a terrorist offense. This article is interested in answering the following questions: What does the cost–benefit decision look like on a single operation? What does the planning process look like? How do terrorists choose between discrete targets? What emotions are felt during the planning and operational phases? What environmental cues are utilized in the decision-making process? Fortunately, much insight is available from the wider criminological literature where studies often provide offender-oriented accounts of the crime commission process. We hypothesize similar factors take place in terrorist decision making and search for evidence within a body of terrorist autobiographies.

(From the journal abstract)

Paul Gill, Zoe Marchment, Emily Corner, and Noémie Bouhana. 2018. ‘Terrorist Decision Making in the Context of Risk, Attack Planning, and Attack Commission’. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism: https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1445501.

Lessons from the Extreme: What Business Negotiators Can Learn from Hostage Negotiations

Editors’ Note: The high-stakes world of the hostage negotiator draws instinctive respect from other negotiators. But if you operate in another domain, you could be excused for thinking that hostage negotiation has nothing to do with you.

That impression, it turns out, is quite often wrong. Here, two researchers draw parallels to several kinds of business and other disputes in which it often seems that one of the parties acts similarly to a hostage taker. Understanding what hostage negotiators have learned to do in response can be a real asset to a negotiator faced with one of these situations.

(From the book abstract)

Taylor, Paul J., and William A. Donohue. 2017. ‘Lessons from the Extreme: What Business Negotiators Can Learn from Hostage Negotiations’. In Negotiator’s Desk Reference, edited by Chris Honeyman and Andrea Kupfer Schneider. DRI Press. www.ndrweb.com.