Interviewing

Academic Publications

An Inventory of Problems–29 (IOP–29) study investigating feigned schizophrenia and random responding in a British community sample

Compared to other Western countries, malingering research is still relatively scarce in the United Kingdom, partly because only a few brief and easy-to-use symptom validity tests (SVTs) have been validated for use with British test-takers. This online study examined the validity of the Inventory of Problems–29 (IOP–29) in detecting feigned schizophrenia and random responding in 151 British volunteers. Each participant took three IOP–29 test administrations: (a) responding honestly; (b) pretending to suffer from schizophrenia; and (c) responding at random. Additionally, they also responded to a schizotypy measure (O-LIFE) under standard instruction. The IOP–29’s feigning scale (FDS) showed excellent validity in discriminating honest responding from feigned schizophrenia (AUC = .99), and its classification accuracy was not significantly affected by the presence of schizotypal traits. Additionally, a recently introduced IOP–29 scale aimed at detecting random responding (RRS) demonstrated very promising results.

(From the journal abstract)

Winters, C. L., Giromini, L., Crawford, T. J., Ales, F., Viglione, D. J., & Warmelink, L. (2020). An Inventory of Problems–29 (IOP–29) study investigating feigned schizophrenia and random responding in a British community sample. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 1–20.

To freeze or not to freeze: A culture-sensitive motion capture approach to detecting deceit

We present a new signal for detecting deception: full body motion. Previous work on detecting deception from body movement has relied either on human judges or on specific gestures (such as fidgeting or gaze aversion) that are coded by humans. While this research has helped to build the foundation of the field, results are often characterized by inconsistent and contradictory findings, with small-stakes lies under lab conditions detected at rates little better than guessing. We examine whether a full body motion capture suit, which records the position, velocity, and orientation of 23 points in the subject’s body, could yield a better signal of deception. Interviewees of South Asian (n = 60) or White British culture (n = 30) were required to either tell the truth or lie about two experienced tasks while being interviewed by somebody from their own (n = 60) or different culture (n = 30). We discovered that full body motion–the sum of joint displacements–was indicative of lying 74.4% of the time. Further analyses indicated that including individual limb data in our full body motion measurements can increase its discriminatory power to 82.2%. Furthermore, movement was guilt- and penitential-related, and occurred independently of anxiety, cognitive load, and cultural background. It appears that full body motion can be an objective nonverbal indicator of deceit, showing that lying does not cause people to freeze.

(From the journal abstract)

Zee, S. van der, Poppe, R., Taylor, P. J., & Anderson, R. (2019). To freeze or not to freeze: A culture-sensitive motion capture approach to detecting deceit. PLOS ONE, 14(4), e0215000.

Analysing openly recorded preinterview deliberations to detect deceit in collective interviews

Sham marriages occur frequently, and to detect them, partners are sometimes interviewed together. We examined an innovative method to detect deceit in such interviews. Fifty-three pairs of interviewees, either friends (truth tellers) or pretended to be friends (liars), were interviewed about their friendship. Just before the interview, they received the questions that would be asked in the interview and were invited to prepare the answers. We told them that these preinterview deliberations would be recorded. Based on the transcripts, we analysed cues to truthfulness (cues expected to be expressed more by truth tellers) and cues to deceit (cues expected to be expressed more by liars). Truth tellers and liars differed from each other, particularly regarding expressing cues to truthfulness. Preinterview deliberations that are recorded with awareness of the interviewees can be used for lie detection purposes. We discuss further venues in this new line of research.

(From the journal abstract)

Vrij, A., Jupe, L. M., Leal, S., Vernham, Z., & Nahari, G. (2020). Analysing openly recorded preinterview deliberations to detect deceit in collective interviews. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(1), 132–141.

Who said what and when? A timeline approach to eliciting information and intelligence about conversations, plots, and plans

The verbal content of interactions (what was said and who said what) can be important as evidence and intelligence information. Across 3 empirical studies, we examined memory for details of an overheard (Experiment 1) or witnessed (Experiments 2 and 3) conversation using a timeline technique adapted for the reporting of conversations between multiple speakers. Although participants in all conditions received the same general instructions, participants assigned to timeline reporting format reported more verbatim information and made fewer sequencing errors than those using a free recall format. In Experiments 2 and 3, using an extended version of the technique, participants using the timeline reporting format also reported more correct speaker attributions and provided more information about the individuals involved, without compromising overall accuracy rates. With a large effect size across experiments (total N = 134), these findings suggest that timeline reporting formats facilitate the reporting of episodic memories and benefit the reporting of conversations.

(From the journal abstract)

Hope, L., Gabbert, F., Kinninger, M., Kontogianni, F., Bracey, A., & Hanger, A. (2019). Who said what and when? A timeline approach to eliciting information and intelligence about conversations, plots, and plans. Law and Human Behavior, 43(3), 263–277.

Memory and the operational witness: Police officer recall of firearms encounters as a function of active response role

Investigations after critical events often depend on accurate and detailed recall accounts from operational witnesses (e.g., law enforcement officers, military personnel, and emergency responders). However, the challenging, and often stressful, nature of such events, together with the cognitive demands imposed on operational witnesses as a function of their active role, may impair subsequent recall. We compared the recall performance of operational active witnesses with that of nonoperational observer witnesses for a challenging simulated scenario involving an armed perpetrator. Seventy-six police officers participated in pairs. In each pair, 1 officer (active witness) was armed and instructed to respond to the scenario as they would in an operational setting, while the other (observer witness) was instructed to simply observe the scenario. All officers then completed free reports and responded to closed questions. Active witnesses showed a pattern of heart rate activity consistent with an increased stress response during the event, and subsequently reported significantly fewer correct details about the critical phase of the scenario. The level of stress experienced during the scenario mediated the effect of officer role on memory performance. Across the sample, almost one-fifth of officers reported that the perpetrator had pointed a weapon at them although the weapon had remained in the waistband of the perpetrator’s trousers throughout the critical phase of the encounter. These findings highlight the need for investigator awareness of both the impact of operational involvement and stress-related effects on memory for ostensibly salient details, and reflect the importance of careful and ethical information elicitation techniques.

(From the journal abstract)

Hope, L., Blocksidge, D., Gabbert, F., Sauer, J. D., Lewinski, W., Mirashi, A., & Atuk, E. (2016). Memory and the operational witness: Police officer recall of firearms encounters as a function of active response role. Law and Human Behavior, 40(1), 23–35.

The Psychology of Criminal Investigation: From Theory to Practice

The contribution of psychological research to the prevention of miscarriages of justice and the development of effective investigative techniques is now established to a point where law enforcement agencies in numerous countries either employ psychologists as part of their staff, or work in cooperation with academic institutions. The application of psychology to investigation is particularly effective when academics and practitioners work together. This book brings together leading experts to discuss the application of psychology to criminal investigation.

This book offers an overview of models of investigation from a psychological and practical view point, covering topics such as investigative decision making, the presentation of evidence, witness testimony, the detection of deception, interviewing suspects and evidence-based police training. It is essential reading for students, researchers and practitioners engaged with police practice, investigation and forensic psychology.

(From the journal abstract)

Griffiths, A., & Milne, R. (Eds.). (2018). The Psychology of Criminal Investigation: From Theory to Practice (1st ed.). Routledge.

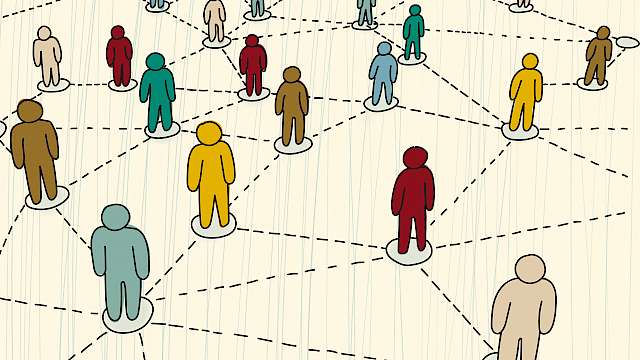

Development of the Reporting Information about Networks and Groups (RING) task: a method for eliciting information from memory about associates, groups, and networks

Eliciting detailed and comprehensive information about the structure, organisation and relationships between individuals involved in organised crime gangs, terrorist cells and networks is a challenge in investigations and debriefings. Drawing on memory theory, the purpose of this paper is to develop and test the Reporting Information about Networks and Groups (RING) task, using an innovative piece of information elicitation software.

Using an experimental methodology analogous to an intelligence gathering context, participants (n=124) were asked to generate a visual representation of the “network” of individuals attending a recent family event using the RING task.

All participants successfully generated visual representations of the relationships between people attending a remembered social event. The groups or networks represented in the RING task output diagrams also reflected effective use of the software functionality with respect to “describing” the nature of the relationships between individuals.

The authors succeeded in establishing the usability of the RING task software for reporting detailed information about groups of individuals and the relationships between those individuals in a visual format. A number of important limitations and issues for future research to consider are examined.

The RING task is an innovative development to support the elicitation of targeted information about networks of people and the relationships between them. Given the importance of understanding human networks in order to disrupt criminal activity, the RING task may contribute to intelligence gathering and the investigation of organised crime gangs and terrorist cells and networks.

(From the journal abstract)

Hope, L, Kontogianni, F, Geyer, K & Thomas, WD 2019, 'Development of the Reporting Information about Networks and Groups (RING) task: a method for eliciting information from memory about associates, groups, and networks', The Journal of Forensic Practice. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-04-2019-0011

Source Handler telephone interactions with covert human intelligence sources: An exploration of question types and intelligence yield

Law enforcement agencies gather intelligence in order to prevent criminal activity and pursue criminals. In the context of human intelligence collection, intelligence elicitation relies heavily upon the deployment of appropriate evidence‐based interviewing techniques (a topic rarely covered in the extant research literature).

The present research gained unprecedented access to audio recorded telephone interactions (N = 105) between Source Handlers and Covert Human Intelligence Sources (CHIS) from England and Wales. The research explored the mean use of various question types per interaction and across all questions asked in the sample, as well as comparing the intelligence yield for appropriate and inappropriate questions.

Source Handlers were found to utilise vastly more appropriate questions than inappropriate questions, though they rarely used open‐ended questions. Across the total interactions, appropriate questions (by far) were associated with the gathering of much of the total intelligence yield. Implications for practise are discussed.

(From the journal abstract)

Jordan Nunan, Ian Stanier, Rebecca Milne, Andrea Shawyer and Dave Walsh, 2020. Source Handler telephone interactions with covert human intelligence sources: An exploration of question types and intelligence yield. Applied Cognitive Psychology.

https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3726

When and How are Lies Told? And the Role of Culture and Intentions in Intelligence-Gathering Interviews

Purpose

Lie‐tellers tend to tell embedded lies within interviews. In the context of intelligence‐gathering interviews, human sources may disclose information about multiple events, some of which may be false. In two studies, we examined when lie‐tellers from low‐ and high‐context cultures start reporting false events in interviews and to what extent they provide a similar amount of detail for the false and truthful events. Study 1 focused on lie‐tellers' intentions, and Study 2 focused on their actual responses.

Methods

Participants were asked to think of one false event and three truthful events. Study 1 (N = 100) was an online study in which participants responded to a questionnaire about where they would position the false event when interviewed and they rated the amount of detail they would provide for the events. Study 2 (N = 126) was an experimental study that involved interviewing participants about the events.

Results

Although there was no clear preference for lie position, participants seemed to report the false event at the end rather than at the beginning of the interview. Also, participants provided a similar amount of detail across events. Results on intentions (Study 1) partially overlapped with results on actual responses (Study 2). No differences emerged between low‐ and high‐context cultures.

Conclusions

This research is a first step towards understanding verbal cues that assist investigative practitioners in saving their cognitive and time resources when detecting deception regardless of interviewees' cultural background. More research on similar cues is encouraged.

(From the journal abstract)

Haneen Deeb, Aldert Vrij, Sharon Leal, Brianna L. Verigin & Steven M. Kleinman, 2020. When and how are lies told? And the role of culture and intentions in intelligence‐gathering interviews. Legal and Criminological Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12171

“Tell me more about this…”: An examination of the efficacy of follow-up open questions following an initial account

In information gathering interviews, follow‐up questions are asked to clarify and extend initial witness accounts. Across two experiments, we examined the efficacy of open‐ended questions following an account about a multi‐perpetrator event.

In Experiment 1, 50 mock‐witnesses used the timeline technique or a free recall format to provide an initial account. Although follow‐up questions elicited new information (18–22% of the total output) across conditions, the response accuracy (60%) was significantly lower than that of the initial account (83%). In Experiment 2 (N = 60), half of the participants received pre‐questioning instructions to monitor accuracy when responding to follow‐up questions. New information was reported (21–22% of the total output) across conditions, but despite using pre‐questioning instructions, response accuracy (75%) was again lower than the spontaneously reported information (87.5%).

Follow‐up open‐ended questions prompt additional reporting; however, practitioners should be cautious to corroborate the accuracy of new reported details.

(From the journal abstract)

Feni Kontogianni, Lorraine Hope, Paul Taylor, Aldert Vrij & Fiona Gabbert, 2020. “Tell me more about this…”: An examination of the efficacy of follow‐up open questions following an initial account. Applied Cognitive Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3675

Fading lies: applying the verifiability approach after a period of delay

We tested the utility of applying the Verifiability Approach (VA) to witness statements after a period of delay. The delay factor is important to consider because interviewees are often not interviewed directly after witnessing an event.

A total of 64 liars partook in a mock crime and then lied about it during an interview, seven days later. Truth tellers (n = 78) partook in activities of their own choosing and told the truth about it during their interview, seven days later.

All participants were split into three groups, which provided three different verbal instructions relating to the interviewer’s aim to assess the statements for the inclusion of verifiable information: no information protocol (IP) (n = 43), the standard-IP (n = 46) and an enhanced-IP (n = 53). In addition to the standard VA approach of analysing verifiable details, we further examined verifiable witness information and verifiable digital information and made a distinction between verifiable details and verifiable sources.

We found that truth tellers reported more verifiable digital details and sources than liars.

(From the journal abstract)

Louise Jupe, Aldert Vrij, Sharon Leal & Galit Nahari, 2019. Fading lies: applying the verifiability approach after a period of delay. Psychology, Crime & Law. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2019.1669594

“Language of Lies”: Urgent Issues and Prospects in Verbal Lie Detection Research

Since its introduction into the field of deception detection, the verbal channel has become a rapidly growing area of research. The basic assumption is that liars differ from truth tellers in their verbal behaviour, making it possible to classify them by inspecting their verbal accounts. However, as noted in conferences and in private communication between researchers, the field of verbal lie detection faces several challenges that merit focused attention. The first author therefore proposed a workshop with the mission of promoting solutions for urgent issues in the field. Nine researchers and three practitioners with experience in credibility assessments gathered for 3 days of discussion at Bar‐Ilan University (Israel) in the first international verbal lie detection workshop. The primary session of the workshop took place the morning of the first day. In this session, each of the participants had up to 10 min to deliver a brief message, using just one slide. Researchers were asked to answer the question: ‘In your view, what is the most urgent, unsolved question/issue in verbal lie detection?’ Similarly, practitioners were asked: ‘As a practitioner, what question/issue do you wish verbal lie detection research would address?’ The issues raised served as the basis for the discussions that were held throughout the workshop. The current paper first presents the urgent, unsolved issues raised by the workshop group members in the main session, followed by a message to researchers in the field, designed to deliver the insights, decisions, and conclusions resulting from the discussions.

(From the journal abstract)

Galit Nahari, Tzachi Ashkenazi, Ronald P. Fisher, Pär-Anders Granhag, Irit Hershkowitz, Jaume Masip, Ewout H. Meijer, et al. 2019. ‘“Language of Lies”: Urgent Issues and Prospects in Verbal Lie Detection Research’. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 24 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12148.

Vulnerable Witnesses: The Investigation Stage’. In Vulnerable People and the Criminal Justice System: A Guide to Law and Practice

This chapter covers one of a number issues in the book Vulnerable People and the Criminal Justice System: A Guide to Law and Practice. The following description is from the publisher's website.

Over the last 25 years there has been a growing recognition that the way in which cases involving the vulnerable are investigated, charged and tried needs to change. Successive judgments of the Court of Appeal have re-enforced the message that advocates and judges have a duty to ensure vulnerable witnesses and defendants are treated fairly and allowed to participate effectively in the process.

How do practitioners recognise who is or may be vulnerable? How should that person be interviewed? What account should police and the CPS take of a defendant's vulnerabilities? How should advocates adjust their questioning of vulnerable witnesses and defendants whilst still complying with their duties to their client? How should judges manage a trial to ensure the effective participation of vulnerable witnesses and defendants? Vulnerable People and the Criminal Justice System, written by leading experts in the field, gathers together for the first time answers to these questions and many more. It provides a practical, informative and thought-provoking guide to recognising, assessing and responding to vulnerability in witnesses and defendants at each stage of the criminal process.

Backed by authoritative research and first-hand experience and drawing on recent case law, this book enables practitioners to deal with cases involving vulnerable people with calmness, authority, and confidence.

(From the book abstract)

Rebecca Milne, and Kevin Smith. 2017. ‘Vulnerable Witnesses: The Investigation Stage’. In Vulnerable People and the Criminal Justice System: A Guide to Law and Practice, edited by Penny Cooper and Heather Norton. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/vulnerable-people-and-the-criminal-justice-system-9780198801115.

Using the Model Statement to Elicit Verbal Differences Between Truth Tellers and Liars: The Benefit of Examining Core and Peripheral Details

Research has shown that a model statement elicits more information during an interview and that truth tellers and liars report a similar amount of extra information. We hypothesised that veracity differences would arise if the total amount of information would be split up into core details and peripheral details. A total of 119 truth tellers and liars reported a stand-out event that they had experienced in the last two years. Truth tellers had actually experienced the event and liars made up a story. Half of the participants were given a model statement during the interview. After exposure to a model statement, truth tellers and liars reported a similar amount of extra core information, but liars reported significantly more peripheral information. The variable details becomes an indicator of deceit in a model statement interview protocol as long as a distinction is made between core and peripheral details.

(From the journal abstract)

Sharon Leal, Aldert Vrij, Haneen Deeb, and Louise Jupe. 2018. ‘Using the Model Statement to Elicit Verbal Differences Between Truth Tellers and Liars: The Benefit of Examining Core and Peripheral Details’. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 7 (4): 610–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2018.07.001.

Extending the Verifiability Approach Framework: The Effect of Initial Questioning

The verifiability approach (VA) is a lie‐detection tool that examines reported checkable details. Across two studies, we attempt to exploit liar's preferred strategy of repeating information by examining the effect of questioning adult interviewees before the VA. In Study 1, truth tellers (n = 34) and liars (n = 33) were randomly assigned to either an initial open or closed questioning condition. After initial questioning, participants were interviewed using the VA. In Study 2, truth tellers (n = 48) and liars (n = 48) were interviewed twice, with half of each veracity group randomly assigned to either the Information Protocol (an instruction describing the importance of reporting verifiable details) or control condition. Only truth tellers revised their initial statement to include verifiable detail. This pattern was most pronounced when initial questioning was open (Study 1) and when the information protocol was employed (Study 2). Thus, liar's preferred strategy of maintaining consistency between statements appears exploitable using the VA.

(From the journal abstract)

Adam Charles Harvey, Aldert Vrij, George Sarikas, Sharon Leal, Louise Jupe, and Galit Nahari. 2018. ‘Extending the Verifiability Approach Framework: The Effect of Initial Questioning’. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 32 (6): 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3465.

Within-Subjects Verbal Lie Detection Measures: A Comparison between Total Detail and Proportion of Complications

We examined whether the verbal cue, proportion of complications, was a more diagnostic cue to deceit than the amount of information provided (e.g., total number of details).

Method

In the experiment, 53 participants were interviewed. Truth tellers (n = 27) discussed a trip they had made during the last twelve months; liars (n = 26) fabricated a story about such a trip. The interview consisted of an initial recall followed by a model statement (a detailed account of an experience unrelated to the topic of investigation) followed by a post‐model statement recall. The key dependent variables were the amount of information provided and the proportion of all statements that were complications.

Results

The proportion of complications was significantly higher amongst truth tellers than amongst liars, but only in the post‐model statement recall. The amount of information provided did not discriminate truth tellers from liars in either the initial or post‐model statement recall.

Conclusion

The proportion of complications is a more diagnostic cue to deceit than the amount of information provided as it takes the differential verbal strategies of truth tellers and liars into account.

(From the journal abstract)

Aldert Vrij, Sharon Leal, Louise Jupe, and Adam Harvey. 2018. ‘Within-Subjects Verbal Lie Detection Measures: A Comparison between Total Detail and Proportion of Complications’. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 23 (2): 265–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12126.

The Cognitive Interview and Its Use for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder

This chapter first discusses the structure of the cognitive interview (CI) and its tenets for eliciting detailed and accurate information from cooperative witnesses. The original CI was comprised of four mnemonics: report everything (RE), mental reinstatement of context (MRC), change temporal order (CTO), and change perspective (CP). The chapter then explores the protocol's effectiveness for application with individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), considering modifications for use with a population group that has difficulties communicating personal experiences. The memory profile of people with ASD suggests that problems arise when people with ASD are called on to use complex strategies to encode or retrieve information. A modified version of the MRC and the use of the sketch plan MRC help people with ASD to provide information that is comparable in accuracy to that of members of the typical population.

(From the journal abstract)

Joanne Richards and Rebecca Milne. 2018. ‘The Cognitive Interview and Its Use for People with Autism Spectrum Disorder’. In The Wiley Handbook of Memory, Autism Spectrum Disorder, and the Law, 245–69. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119158431.ch13.

Using Specific Model Statements to Elicit Information and Cues to Deceit in Information-Gathering Interviews

Model Statements are designed to modify an interviewee's expectation of the amount of details required during an interview. This study examined tailored Model Statements, emphasising either spatial (Spatial-MS), or temporal (Temporal-MS) details, compared to a control condition (no-MS). Participants (63 liars, 63 truth-tellers) were randomly allocated to one of three interviewing conditions. Truth-tellers honestly reported a spy mission, whereas liars performed a covert mission and lied about their activities. The Spatial-MS elicited more spatial details than the control, particularly for truth-tellers. The Temporal-MS elicited more temporal details than the control, for truth-tellers and liars combined. Results indicate that the composition of different Model Statements increases the amount of details provided and, regarding spatial details, affects truth-teller's and liar's statements differently. Thus, Model Statements can be constructed to elicit information and magnify cues to deceit.

(From the journal abstract)

Cody Porter, Aldert Vrij, Sharon Leal, Zarah Vernham, Giacomo Salvanelli, and Niall McIntyre. 2018. ‘Using Specific Model Statements to Elicit Information and Cues to Deceit in Information-Gathering Interviews’. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 7 (1): 132–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.10.003.

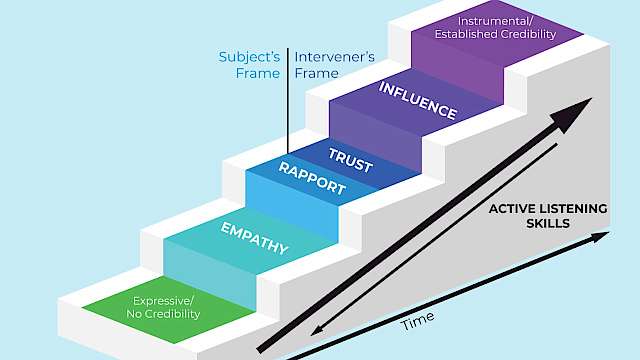

Reframing Intelligence Interviews: The Applicability of Psychological Research to HUMINT Elicitation

Effective discovery and subsequent threat mitigation is predicated on accurate, timely and detailed actionable information. Information, an important element within intelligence and investigation ensures appropriate judicial disposal in Law Enforcement Agency’s (LEA) efforts to bring offenders to justice.

The value of information to delivering community safety is reflected in associated policy, practice, and process. Effective interviewing, in both its formal and informal interactive states, offers a significant opportunity to elicit critical strategic and tactical information that both informs and drives LEA activity.

It is unexpected then, that within the context of information collection, not only are human interactions between LEA and members of the public under-exploited but also, when the intention is to collect information, how unsatisfactorily it is approached and executed.

It is apparent that the required elicitation skills, including rapport building and the identification of source motivation, are not sufficiently taught, and the governing policy is overly cautious with a negligible evidence base.

Whilst this chapter focuses on the psychological aspects of techniques available for gathering information, and in particular intelligence collection, the underlying psychological principles of conducting an effective interview are relevant to a wider audience.

(From the book abstract)

Stanier, I. P., and Jordan Nunan (2018). Reframing Intelligence Interviews: The Applicability of Psychological Research to HUMINT Elicitation. In A. Griffiths, & R. Milne (Eds.), The Psychology of Criminal Investigation: From Theory to Practice (pp. 226-248). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637211

Cross-Cultural Verbal Deception

Background

‘Interviewing to detect deception’ research is sparse across different Ethnic Groups. In the present experiment, we interviewed truth tellers and liars from British, Chinese, and Arab origins. British interviewees belong to a low‐context culture (using a communication style that relies heavily on explicit and direct language), whereas Chinese and Arab interviewees belong to high‐context cultures (communicate in ways that are implicit and rely heavily on context).

Method

Interviewees were interviewed in pairs and 153 pairs took part. Truthful pairs discussed an actual visit to a nearby restaurant, whereas deceptive pairs pretended to have visited a nearby restaurant. Seventeen verbal cues were examined.

Results

Cultural cues (differences between cultures) were more prominent than cues to deceit (differences between truth tellers and liars). In particular, the British interviewees differed from their Chinese and Arab counterparts and the differences reflected low‐ and high‐context culture communication styles.

Conclusion

Cultural cues could quickly lead to cross‐cultural verbal communication errors: the incorrect interpretation of a cultural difference as a cue to deceit.

(From the journal abstract)

Leal, Sharon, Aldert Vrij, Zarah Vernham, Gary Dalton, Louise Jupe, Adam Harvey, and Galit Nahari. 2018. ‘Cross-Cultural Verbal Deception’. Legal and Criminological Psychology, June. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12131.

Lessons from the Extreme: What Business Negotiators Can Learn from Hostage Negotiations

Editors’ Note: The high-stakes world of the hostage negotiator draws instinctive respect from other negotiators. But if you operate in another domain, you could be excused for thinking that hostage negotiation has nothing to do with you.

That impression, it turns out, is quite often wrong. Here, two researchers draw parallels to several kinds of business and other disputes in which it often seems that one of the parties acts similarly to a hostage taker. Understanding what hostage negotiators have learned to do in response can be a real asset to a negotiator faced with one of these situations.

(From the book abstract)

Taylor, Paul J., and William A. Donohue. 2017. ‘Lessons from the Extreme: What Business Negotiators Can Learn from Hostage Negotiations’. In Negotiator’s Desk Reference, edited by Chris Honeyman and Andrea Kupfer Schneider. DRI Press. www.ndrweb.com.

The Benefits of a Self-Generated Cue Mnemonic for Timeline Interviewing

Reliable information is critical for investigations in forensic and security settings; however, obtaining reliable information for complex events can be challenging. In this study, we extend the timeline technique, which uses an innovative and interactive procedure where events are reported on a physical timeline. To facilitate remembering we tested two additional mnemonics, self-generated cues (SGC), which witnesses produce themselves, against other-generated cues (OGC) which are suggested by the interviewer.

One hundred and thirty-two participants witnessed a multi-perpetrator theft under full or divided attention and provided an account using the timeline comparing the efficacy of SGC, OGC, and no cues (control). Mock-witnesses who used self-generated cues provided more correct details than mock-witnesses in the other-generated or no cues conditions, with no cost to accuracy, under full but not under divided attention. Promising results on SGC suggest that they might be a useful addition to current interviewing techniques.

(From the journal abstract)

Kontogianni, Feni, Lorraine Hope, Paul J. Taylor, Aldert Vrij, and Fiona Gabbert. 2018. ‘The Benefits of a Self-Generated Cue Mnemonic for Timeline Interviewing’. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, April. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2018.03.006.

Culture Moderates Changes in Linguistic Self-Presentation and Detail Provision When Deceiving Others

Change in our language when deceiving is attributable to differences in the affective and cognitive experience of lying compared to truth telling, yet these experiences are also subject to substantial individual differences. On the basis of previous evidence of cultural differences in self-construal and remembering, we predicted and found evidence for cultural differences in the extent to which truths and lies contained self (versus other) references and perceptual (versus social) details.

Participants (N = 320) of Black African, South Asian, White European and White British ethnicity completed a catch-the-liar task in which they provided genuine and fabricated statements about either their past experiences or an opinion and counter-opinion. Across the four groups we observed a trend for using more/fewer first-person pronouns and fewer/more third-person pronouns when lying, and a trend for including more/fewer perceptual details and fewer/more social details when lying.

Contrary to predicted cultural differences in emotion expression, all participants showed more positive affect and less negative affect when lying. Our findings show that liars deceive in ways that are congruent with their cultural values and norms, and that this may result in opposing changes in behaviour.

(From the journal abstract)

Taylor, Paul J., Samuel Larner, Stacey M. Conchie, and Tarek Menacere. 2017. ‘Culture Moderates Changes in Linguistic Self-Presentation and Detail Provision When Deceiving Others’. Royal Society Open Science 4 (6). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.170128.

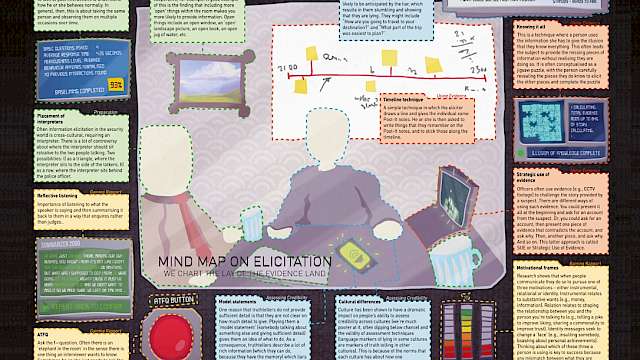

Research on the Timeline Technique

The research in this paper by CREST member Professor Lorraine Hope was used as the basis for our short guide to using The Timeline Technique in interviewing. The technique can be useful in helping interviewees recall and report events from a particular timeframe. In this paper it is demonstrated that using the technique aids more accurate recall of details of an event than using a free-recall approach (e.g. by asking someone to repeat everything they can remember about an event). You can download the guide here. You can download this paper via the link below the abstract.

Who? What? When? Using a timeline technique to facilitate recall of a complex event

Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition

Volume 2, Issue 1, March 2013, Pages 20–24

Authors: Lorraine Hope, Rebecca Mullis, Fiona Gabbert

Abstract

Accurately recalling a complex multi-actor incident presents witnesses with a cognitively demanding retrieval task. Given the important role played by temporal context in the retrieval process, the current research tests an innovative timeline technique to elicit information about multiple perpetrators and their actions. Adopting a standard mock witness paradigm, participants were required to provide an account of a witnessed event. In Experiment 1, the timeline technique facilitated the reporting of more correct details than a free recall, immediately and at a two-week retention interval, at no cost to accuracy. Accounts provided using the timeline technique included more correct information about perpetrator specific actions and fewer sequencing errors. Experiment 2 examined which mnemonic components of the timeline technique might account for these effects. The benefits of exploiting memory organization and reducing cognitive constraints on information flow are likely to underpin the apparent timeline advantage.

Highlights:

- Accurately recalling a complex multi-actor incident presents witnesses with a cognitively demanding retrieval task.

- Adopting a mock witness paradigm, we tested an innovative timeline technique to elicit information about a complex crime.

- The timeline technique facilitated reporting of more correct details than a free recall, at no cost to accuracy, both immediately and after a delay.

- Timeline reports included more correct information about perpetrator specific actions and fewer incident sequencing errors.

- Exploiting memory organization and reducing constraints on information flow may underpin the apparent timeline advantage.

You can download this paper at the following link:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221136811300003X

Research on the verifiability approach in interviewing

The research in this paper contributed to the CREST guide on checkable details in interviewing. It demonstrates a method interviewers can use to aid in determining whether someone is telling the truth or not. You can download the guide here. For more information on the research behind the guide you can download this paper via the link below.

The Verifiability Approach: Countermeasures Facilitate its Ability to Discriminate Between Truths and Lies

Applied Cognitive Psychology

Volume 28 Issue 1 (January/February 2014), Pages 122-128

Author(s): Galit Nahari, Aldert Vrij, Ronald P. Fisher

DOI: 10.1002/acp.2974

Abstract

According to the verifiability approach, liars tend to provide details that cannot be checked by the investigator and awareness of this increases the investigator's ability to detect lies. In the present experiment, we replicated previous findings in a more realistic paradigm and examined the vulnerability of the verifiability approach to countermeasures. For this purpose, we collected written statements from 44 mock criminals (liars) and 43 innocents (truth tellers), whereas half of them were told before writing the statements that the verifiability of their statements will be checked. Results showed that ‘informing’ encouraged truth tellers but not liars to provide more verifiable details and increased the ability to detect lies. These findings suggest that verifiability approach is less vulnerable to countermeasures than other lie detection tools. On the contrary, in the current experiment, notifying interviewees about the mechanism of the approach benefited lie detection.

You can download this paper at the following link.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acp.2974/abstract