Traditional Crisis Negotiation Models

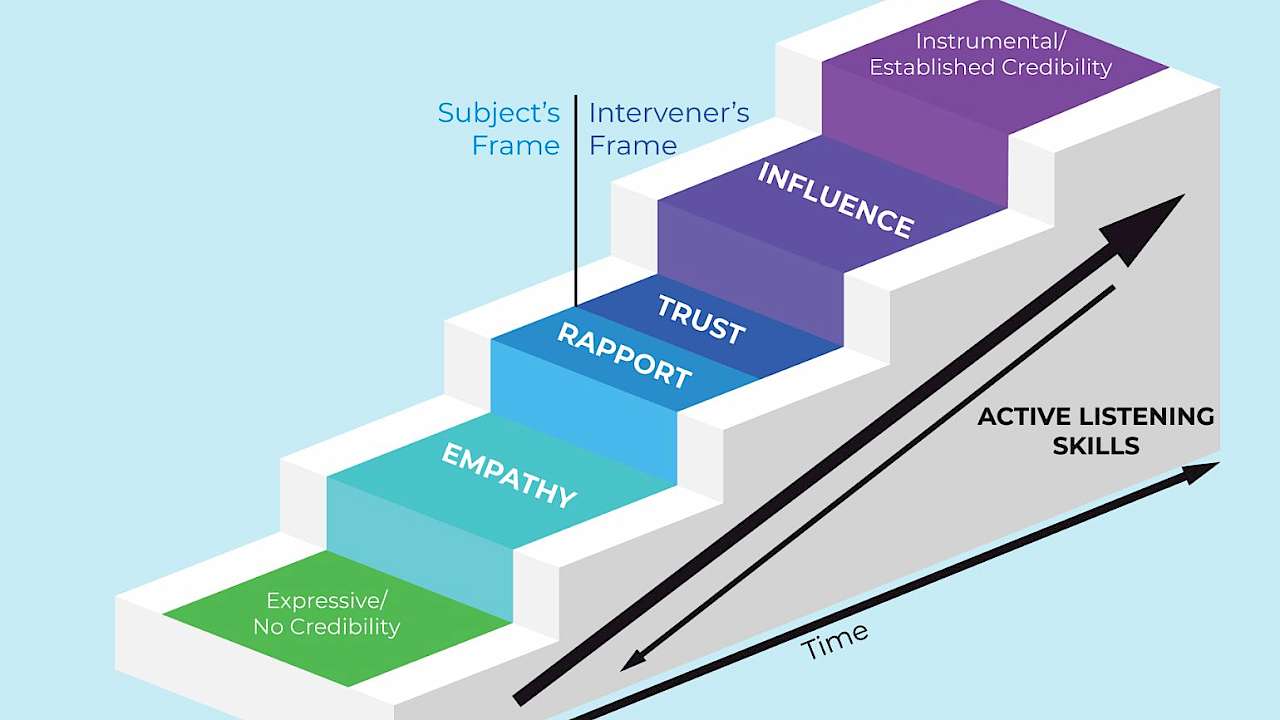

Suicide negotiation is a high-stakes, complex and unpredictable task that specialised police officers (i.e., negotiators) perform on a day-to-day basis. The goal of the negotiator is to save the life of the person in crisis. The question is, however, how to reach that goal without someone getting hurt? To bring order to these unstable interactions, law enforcement agencies and academics have collaborated, researched and constructed simplified negotiation models for hostage (Vecchi et al., 2005), terrorist (Ireland & Vecchi, 2009) and suicide (Vecchi et al., 2019) negotiations. The latter model being called: the revised Behavioural Influence Stairway Model (see figure 1); specifically tailored for dealing with mentally unstable individuals considering or attempting suicide.

In essence, the stairway model provides the negotiator with a path towards behavioural change of the person in crisis, and consists of four sequential stages:

- Empathy – trying to understand the situation, feeling and motives of the subject.

- Rapport – creating a smooth, positive and harmonious connection with the subject.

- Trust – being perceived as honest, sincere and capable of delivering on promises.

- Influence – inducing a change in the subject’s state of mind.

The underlying mechanism of this stairway metaphor is based on the axiom of linearity. Meaning, one stage (e.g., empathy) must first be completed before the other stage (e.g., rapport) can occur. Following this line of reasoning, behavioural change is only possible if all stages (empathy, rapport, trust and influence) are sequentially achieved. Vecchi et al. (2019, p. 236) explicitly state: “Behavioral change will occur only if the previous four stages have been successfully completed”.

Real-Life Experiences of Practitioners

Although practitioners generally view the stairway models (Vecchi et al., 2005; Ireland & Vecchi, 2009; Vecchi et al., 2019) as a good foothold during negotiations, there have been cases where negotiators deviate from the theory. The third and fourth contributors to this article experienced opportunities for accelerated influence in their decades of crisis negotiation practices, including hostage, terrorist and suicide negotiations. They confirmed the mutual occurrence of this phenomenon through a survey with 84 negotiators from 14 different countries, of which 78% agreed to have experienced the same in (some of) their operations. Accelerated influence can be described as short-circuiting the negotiation, omitting one or more of the stairway stages (e.g., empathy, rapport, or trust), reaching influence quickly and establishing different types of behavioural change early in the negotiation.

Empirical Experimentation

To explore this phenomenon of accelerated influence, researchers at the University of Twente (Netherlands) began investigating its effect in the suicide negotiation setting (Oostinga et al., in prep). In an online pre-programmed suicide negotiation, two negotiation styles were compared: the traditional approach versus accelerated approach. Through various methods (video, script and an imagination exercise) participants were immersed in a fictitious situation where they were standing at the edge of a bridge contemplating suicide. Subsequently, they were contacted by a negotiator via text-messages. In random order, the negotiator performed either an accelerated approach (directly asking for a behavioural change followed by the stairway stages) or the traditional approach (following the stairway stages and then asking for a behavioural change); without the participants knowing which treatment they received.

To illustrate, in the accelerated approach, the crisis negotiator immediately asked for a change in behaviour of the participant: “I can see you from a distance and I get really frightened when I see you at the other side of the fence, because I think you might fall by accident before you are ready. Why don’t you come to the other side of the fence, so we can continue this conversation in a safer manner?”. Whereas, in the traditional approach, the crisis negotiator first attempted to build a relationship based on empathy, rapport and trust with the participant before asking for a change in behaviour. For example, the negotiator tried to establish trust by saying: “I am here for you and will do all that I can to support you. It may feel like you were alone in this before we started talking, to reassure you I do have experience supporting people in similar situations in finding a way forward”.

Overall, the experiment confirmed the efficacy of the traditional approach, showing a 55% compliance rate towards the crisis negotiator’s safety suggestion (i.e., behavioural change). However, in 32% of the cases, the negotiator was able to reach behavioural change from the onset of the interaction. Even more so, both groups ended with medium to high levels of empathy, rapport, and trust. Thus, even a failed accelerated attempt did not seem to harm the relationship between the crisis negotiator and participant.

Discussion and Future Exploration

While the early evidence, indicating the potential for accelerated influence, is certainly promising, it is essential to validate these findings through additional studies that incorporate face-to-face interactions. Besides, it is worth noting that the sample consisted mainly of participants with a Western background (45% Dutch, 35% German). Therefore, future studies could explore potential differences in achieving accelerated influence between Western and non-Western individuals. Last, the current study focused on suicide negotiations. Future research could investigate whether the effect of accelerated influence is similar in hostage and terrorism negotiations. Nonetheless, the practical and academical discovery of accelerated influence in suicide crisis negotiation can initiate a thought-provoking discussion about re-evaluating the conventional stairway metaphor. One could consider a more nuanced version of the stairway model, or even start envisioning different types of new metaphors. For example, a climbing wall metaphor consisting of:

- Multiple deployment routes which offer various approaches to reach a safe resolution.

- Different paths of varying complexity suitable for negotiators of different experience levels; from “linear and structured” to “non-linear and flexible” routes.

- Shortcuts that allow negotiators to skip stages when feasible.

With this article, we hope to encourage scholars and practitioners to join this conversation and rethink the linear proposition, visualise and test different metaphors for improved negotiation training and conduct further empirical research into the phenomenon of accelerated influence.

Read more

Ireland, C. A. & Vecchi, G. M. (2009). The Behavioral Influence Stairway Model (BISM): framework for managing terrorist crisis situations? Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 1(3), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434470903017722

Oostinga, M. S. D., Van der Klok, N., Watson, S. J. & Russell, L. C. (in preparation). Timing of behaviour change in crisis negotiation: A temporal test of the Revised Behavioural Influence Stairway Model.

Vecchi, G. M., Van Hasselt, V. B. & Romano, S. J. (2005). Crisis (hostage) negotiation: current strategies and issues in high-risk conflict resolution. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(5), 533–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2004.10.001

Vecchi, G. M., Wong, G. K., Wong, P. W. & Markey, M. A. (2019). Negotiating in the skies of Hong Kong: The efficacy of the Behavioral Influence Stairway Model (BISM) in suicidal crisis situations. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 48, 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2019.08.002

Wells, S., Taylor, P. & Giebels, E. (2013). ‘Crisis negotiation: From suicide to terrorism intervention’. Eds. Mara Olekalns & Wendi Adair. Handbook of Negotiation Research. Melbourne: Elgar. Edwards Publishing. Available at: https://goo.gl/j58KqN

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)