‘The rise of the far right’ in Ireland has been widely discussed in mainstream media, however, the extent of this ‘rise’ remains largely unknown. Additionally, with much uncertainty remaining about the future and the ongoing impact of COVID-19, it is perhaps unsurprising that conspiracy theory belief also appears to be on the rise in Ireland.

Is there a nexus between the two? While much has been written about the psychology of conspiracy theories and how best to measure the construct, there remains a dearth of any applied research in the Irish context.

During the global pandemic, there has been a rise in conspiracy theory production and dissemination, with many theories having an international component while also demonstrating a more localised impact. For example, the theory of a (globally) planned pandemic to facilitate (national) government control. The nature of conspiracy theories is such that once they are in the public sphere, they can be influential in various aspects of decision making, although the extent of this remains poorly measured.

Looking for answers

Since March 2020, Ireland has used ‘rolling lockdowns’ in attempts to lessen the impact of COVID-19. This has resulted in varying levels of frustration with pandemic related government policies, such as travel limitations, mask requirements, and vaccine rollout. In turn, this has compounded existing dissatisfaction with government policies (relating to homelessness, housing, and unemployment) and created a space for angry and disillusioned people looking for answers.

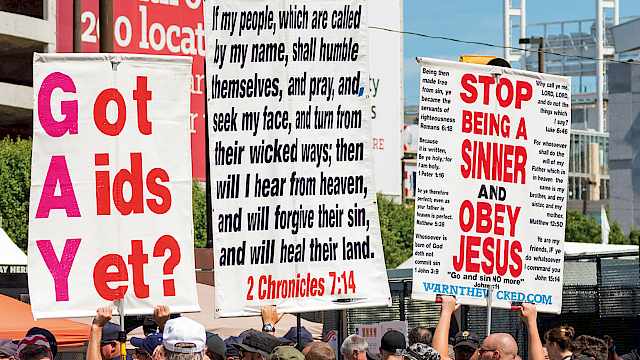

Some people are finding these answers in far-right ideologies, COVID-19 conspiracy theories, and ‘scamdemic’ rhetoric. What we do not yet know, and need to understand more fully, is the extent of belief in far-right ideologies in Ireland. This will allow us to examine the nature of the relationships between these beliefs and COVID-19 conspiracy creation and dissemination and understand the potential impact on behaviour.

To date, despite Ireland having some conditions which may seem conducive to the growth of the far right (such as economic change, fluctuating employment levels, a housing crisis, and continued emigration and immigration), it has remained the less popular option.

The results of the 2020 General Election demonstrated how little palate the Irish voting public have for a right-wing nationalist party. Neither the National Party nor the Irish Freedom Party (both considered far-right in terms of ideology) has representation at a local or national level and, between them, received less than 1% of the vote in the 2020 election. This could be because Sinn Féin has increased in popularity and provides the alternative people seek in the Irish context.

The Far Right and COVID-19 Conspiracy

However, as Sinn Féin has become more mainstream, this may provide the necessary ‘space’ for the far right to begin to flourish. To this end, there are vocal proponents of right-wing ideology within the Irish context, and interestingly these individuals are now often linked with the dissemination of COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Currently, we find intertwined discourses created around anti-lockdown restrictions, anti-mask and anti-vaccination campaigns, as well as anti-immigration views more broadly.

As Sinn Féin has become more mainstream, this may provide the necessary ‘space’ for the far right to begin to flourish.

Increased online monitoring by Moonshot (following the events at Capitol Hill in January 2021) has led to some shifts in online media use by far-right proponents in Ireland. For example, according to Gallagher and O’Connor (2021), Telegram has become one of the main communication tools for Irish far-right groups, influencers, and supporters. Their analysis illustrates that the far-right is intersecting with Irish anti-lockdown and COVID-19 conspiracy theory Telegram channels, actively encouraging followers to spread disinformation.

Realistically, in Ireland as elsewhere, more data are needed to provide a clear picture of how the far right interacts with COVID-19 conspiracy theories (and indeed the far left). There are inherent challenges in gauging the popularity of an ideology within a population. However, much of what we assume to know about ‘the rise of the far right’ in Ireland is based on media speculation and a limited number of empirical studies.

As the COVID-19 pandemic does not seem to be ending any time soon, there is an urgent need for in-depth studies of these communities, their messaging, and the evolving channels they communicate through. Comparison of in- and between- country change will also help understand and disrupt two global challenges, with significant national impacts.

Read more

- Grodzicka, E. D. (2021). Taking vaccine regret and hesitancy seriously. The role of truth, conspiracy theories, gender relations and trust in the HPV immunisation programmes in Ireland. Journal for Cultural Research, 25:1, 69-87. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14797585.2021.1886422

- The Irish Times, The far right rises: Its growth as a political force in Ireland (19 September 2020), https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/the-far-right-rises-its-growth-as-a-political-force-in-ireland-1.4358321

- Douglas, K. M., Uscinski, J. E., Sutton, R. M., Cichocka, A., Nefes, T., Ang, C. S. Deravi, F. (2019). Understanding conspiracy theories. Advances in Political Psychology, 40(1), 3-35. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2019-16213-001

- Brotherton, R., French, C., & Pickering, A. (2013). Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: the generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Frontiers in Psychology. 4. 279 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279/full

- Goreis, A. & Voracek, M. (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Psychological Research on Conspiracy Beliefs: Field Characteristics, Measurement Instruments, and Associations With Personality Traits. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00205/full

- Douglas, K. M. (2021). COVID-19 conspiracy theories. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 270–275. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1368430220982068

- Shahsavari, S., Holur, P., Wang, T., Tangherlini, T. R. & Roychowdhury, V. (2020). Conspiracy in the time of corona: automatic detection of emerging COVID-19 conspiracy theories in social media and the news. Journal of Computational Social Science, 3, 279–317. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42001-020-00086-5

- Pummerer, L., Bohm, R., Lilleholt, L., Winter, K., Zettler, I., Sassenberg, K. (2021). Conspiracy Theories and Their Societal Effects During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1-11 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/19485506211000217

- Charalambous, G., & Lamprianou, I. (2016). Societal Responses to the Post-2008 Economic Crisis among South European and Irish Radical Left Parties: Continuity or Change and Why? Government and Opposition, 51 (2): 269. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/government-and-opposition/article/societal-responses-to-the-post2008-economic-crisis-among-south-european-and-irish-radical-left-parties-continuity-or-change-and-why/9C9BF9A83E536CDBB9687ACD84E16754

- O’Malley, E. (2008). Why is there no Radical Right Party in Ireland? Working Papers in International Studies Series. (Paper No. 2008-1). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/29652064_Why_is_there_no_Radical_Right_Party_in_Ireland

- Websites of vocal far-right proponents in Ireland Gemma O’ Doherty (https://gemmaodoherty.com/) and Rowan Croft (aka Grand Torino) (https://wbn998.wixsite.com/grandtorino)

- Gallagher, A. & O’Connor, C. (2021). Layer of Lies: A First Look at Irish Far-Right Activity on Telegram. Report for Institute of Strategic Dialogue. https://www.isdglobal.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Layers-of-Lies.pdf

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: National Party members at the March for Innocence, 2020 | Flickr.com Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)