The Brexit campaign, the election of Donald Trump, the rise of extreme political parties across Europe, and the emergence of fake news on social media have all been tightly intertwined with conspiracy theories. Joe Uscinski shares five things social scientists have learned about conspiracy theories.

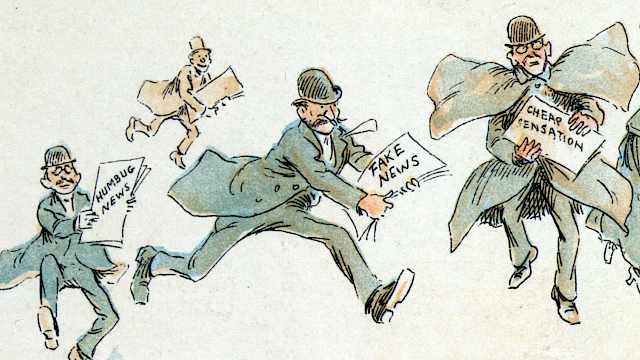

With all the news surrounding conspiracy theories, perhaps it is time to take stock of what we really know about them. Of course, the definition of conspiracy theory is itself open to debate. I understand conspiracy theories as an unofficial account of events that explains outcomes through a small group, working in secret, against the common good. Here are five things social scientists have learned about such accounts in the last decade.

1. Conspiracy theories are both timely and timeless

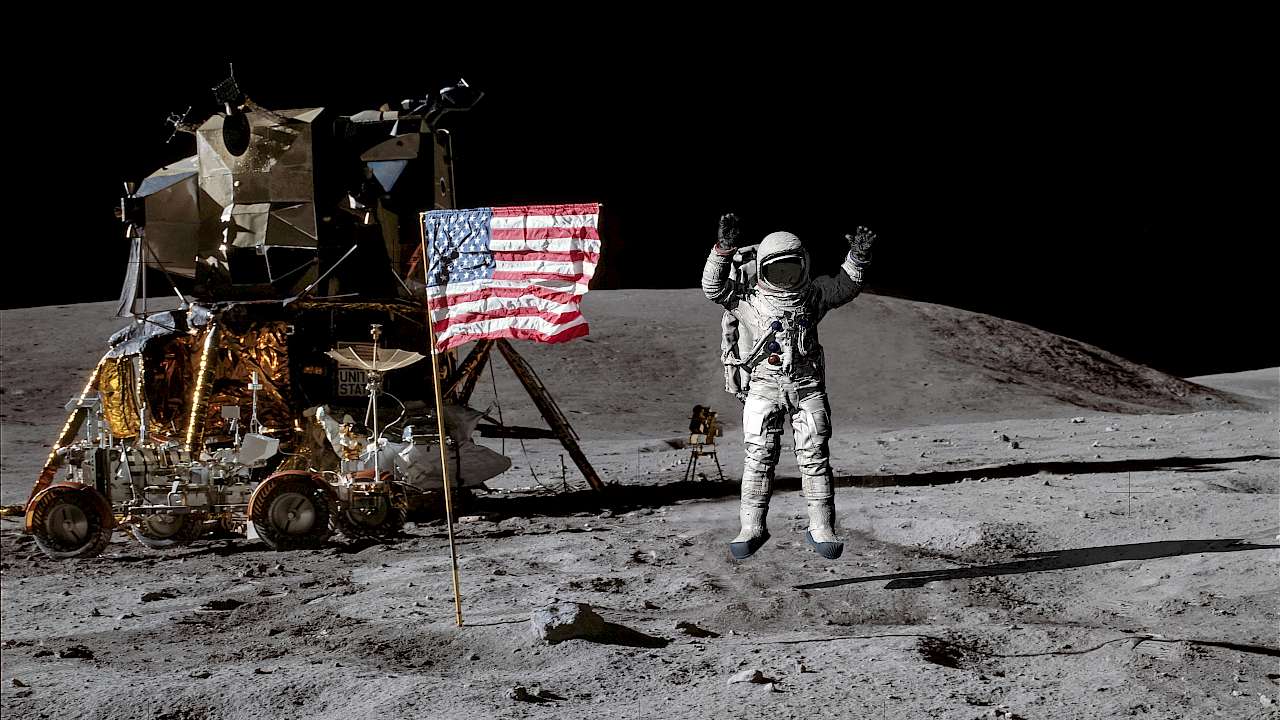

As far back as recorded history goes, conspiracy theories have been part of the human condition. No age particularly stands out as more conspiratorial than another. In recent decades, events have triggered conspiracy theories focusing on the assassination of JFK, the death of Princess Diana, and the terror attacks of 9/11.

Before that, there were red scares and fears of monopoly trusts, Freemasons, and Illuminati. Conspiracy theories are alive and well, but there is no reason to conclude conspiracy theorising has hit an apex.

2. Everybody believes in conspiracy theories

In the most neutral terms, conspiracy theorists are anyone who believes in conspiracy theories. We track how popular conspiracy theories are with opinion polling, but most polls only ask about one or a few conspiracy theories.

If pollsters could ask about an unlimited number of conspiracy theories, it is likely that everyone would express belief in at least one if not several. With this said, there is heterogeneity: some people believe in very few conspiracy theories, others have a conspiracy-riven mentality and believe in many.

3. Conspiracy theories must coincide with existing dispositions

There is an assumption that conspiracy theories spread now more than ever because of the internet. While it is true that information can travel farther and faster than ever before, it’s not necessarily true that conspiracy theories have benefited from this more than any other type of information medium.

There are many fringe theories skulking around the net, but studies of web traffic show that few people take an interest. The reason is simple: for people to believe in a given conspiracy theory, those people must not only have a predilection for conspiracy theorising, but the theories themselves must also harmonise with individuals’ other predispositions.

These include their political party or ideology, their racial and religious viewpoints, and their other worldviews.

To wit, Muslims, in very high numbers, question the official accounts of the 9/11 and 7/7 attacks because it is easier for them to place the blame for these events on a group other than their own. Devout Catholics will not believe in DiVinci Code theories suggesting that Jesus fathered offspring with a prostitute; these beliefs resonate better with non-Catholics.

Conspiracy theories help out-of-power groups cope with their lowly status ... Put simply, conspiracy theories are for losers.

9/11 Truth theories were only able to convince conspiracy-minded Democrats in the US; Republicans would not believe that President Bush blew up the Twin Towers.

There are millions of conspiracy theories out there, but most won’t amass much following. People are fickle with their beliefs and aren’t quick to fall prey to any given conspiracy theory.

4. Power asymmetries can ripen conspiracy theories

The more we learn about conspiracy theories, the more we find that they can act as a bellwether, telling us who is afraid of who, what, and when.

They are conjectures about who has power and what they do with it when no one is looking. Rarely do conspiracy theories accuse the weak (e.g., the homeless) of conspiring.

Therefore, accusations of conspiracy levied by out-of-power groups against in-power groups tend to resonate most in society. Groups who feel that they are ruled by another will experience anxiety due to their perceived powerlessness.

As a coping mechanism, conspiracy theories help out of power groups cope with their lowly status, close ranks, alert to potential oncoming dangers, and seek redemption. When a group’s power increases, the anxiety driving the conspiracy theorising subsides. Put simply, conspiracy theories are for losers.

5. Conspiracy theories can have serious consequences

People who are convinced that terrorism is a government perpetuated hoax will be less supportive of, and less compliant with, government initiatives for fighting terrorism. Even worse, conspiracy theories can lead people to justify violence.

Which individual conspiracy theorist will resort to violence is impossible to predict. But which types of people will tend towards violent acts is not entirely unpredictable.

Social scientists have learned much about those who think in conspiratorial terms; two important characteristics are that (1) they view conspiring as an acceptable means of achieving goals, and (2) they are more accepting of violence. People who believe powerful groups are out to get them will eventually fight fire with fire.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)