The revival of al-Qaeda as Hamza bin Laden rose in the leadership ranks indicated an intergenerational transmission of resilience to stress associated with involvement in terrorism. Being raised in terrorist camps and hideouts in Sudan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and detained for several years in Iran, Hamza was exposed to stress associated with terrorism throughout his developmental years.

Based on al-Qaeda leaders’ observations that they had communicated to Osama bin Laden, Hamza also developed a remarkable resilience while he had been homeschooled in exile by his mother who had a doctoral degree and professional experience in child psychology. Owing to his resilience, Hamza was determined to carry over his father’s destructive mission, as indicated in his declaration of revenge.

Stress of involvement in terrorism

Previous research has identified four types of stress associated with involvement in terrorism in al-Qaeda members: security stress, the stress of enforced idleness, diversity stress, and incarceration stress.

Terrorists conceptualised security stress as a result of exposure to spying aircraft, advanced surveillance technologies, and infiltration of spies. The stress of enforced idleness occurred in response to a long-term deprivation of activity owing to the nature of covert terrorist operations.

Diversity stress was experienced in multicultural settings by both local and foreign terrorists owing to psychosocial differences between them.

Incarceration stress caused by a fear of being tortured or otherwise abused during imprisonment was described as “a psychological crisis, … tension, and being occupied with the thought.”

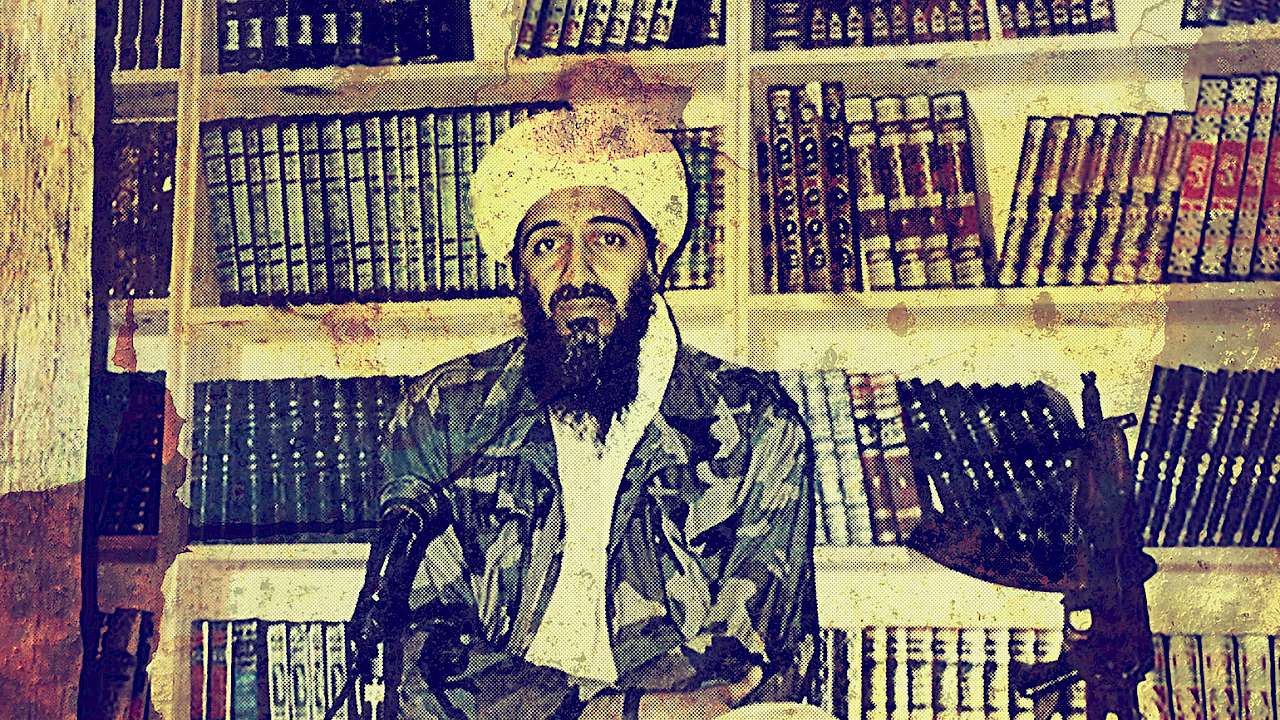

Based on an analysis of ‘Bin Laden’s Bookshelf’ – documents recovered from bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound following his capture, I have investigated al-Qaeda’s conceptualisation of resilience to these types of stress.

Resilience to stress of involvement in terrorism

Hamza encountered all four types of stress but it did not deter him from terrorist activity. On the contrary, he expressed frustration in a letter to his father that, because of his detention, he could not take part in al-Qaeda operations.

The factors that shaped Hamza’s resilience to stress were a deep emotional attachment to his father whom he perceived as a role model, inspiration and care from his mother, affection to his wife and children, mentorship from al-Qaeda elders, social support from al-Qaeda members, strong religious beliefs, and finding meaning in his stressful experiences as predestined to prepare him for jihad and martyrdom.

Similarly, other al-Qaeda members attributed their resilience to stress to making meaning of stressful experiences through strong religious beliefs, willingness to endure hardships, self-sacrifice, guidance from leaders who fostered a learn-and-adapt attitude, and social support from fellow members.

Resilience to stress was at the core of al-Qaeda’s training that aimed to prepare its members spiritually, militarily, and psychologically. Further, al-Qaeda’s stress management strategy was based on preventing exhaustion and burnout from work overload that would lead to what they termed the “unrest mind”, which in turn would weaken faith and deter motivation for jihad.

Moreover, al-Qaeda trained its members in security-enhancing behaviours to foster their resilience to stress. Al-Qaeda’s training was based on maintaining a balance between external and internal loci of control. External locus of control was encouraged through religious coping with stressors that were unavoidable.

At the same time, Osama bin Laden was a strong proponent of internal locus of control. He attributed security failures to human errors and believed that some members are simply not fit to perform operations despite the training provided and their religious devotion. Apparently, al-Qaeda leadership believed that developing resilience through training and experience is not enough and that resilience depends on certain personality traits.

Neuroticism and resilience to security stress

Emotional stability is a personality trait that correlates with resilience. In a large twin study on resilience and personality traits, Amstadter, Moscati, Maes, Myers, and Kendler (2016) found that neuroticism was the strongest predictor of resilience, considering both genetic and environmental factors, thus, suggesting that persons with higher emotional stability are more resilient to stress.

Similarly, Oshio, Taku, Hirano, and Saeed (2018) in a meta-analysis of 30 studies on resilience and personality in the general population supported that low neuroticism correlates with resilience to stress. Although there is a lack of consensus amongst terrorism researchers regarding any personality traits or a psychological profile specific to terrorists, the most important personality characteristics that al-Qaeda valued in recruits were associated with low neuroticism and described as emotional stability, calmness, patience, and self-control.

Given the value of these traits, it is unsurprising that Hamza had been often praised by al-Qaeda leaders for his calmness, patience, and discipline, contrary to his half-brother Saad who was blamed for his impulsivity and reckless behaviour, to which his death was attributed. More generally, those al-Qaeda members who expressed emotional instability would be removed from military operations and management positions and assigned other work.

Introversion and resilience to the stress of enforced idleness

Contrary to the correlation between resilience and extraversion in the general population, al-Qaeda conceptualised resilience to the stress of enforced idleness in terms of introversion because introverted members were more capable of maintaining quietness and secretiveness.

When confined to isolation and idleness for operational security, terrorists who were introverted would spend their time learning and introspecting, whereas those who were extraverted would underestimate the risks and commit security errors because of their need for external stimulation and communication.

Agreeableness and resilience to diversity stress

Agreeableness has the weakest correlation with resilience in the general population, in comparison to other personality traits in the five factors model. However, al-Qaeda fostered agreeableness to increase its members’ resilience to diversity stress. Foreign terrorists, who were expected to appreciate the hospitality of local supporters, were advised to use silence to express their disagreements with local hosts.

Those foreign members who could get along well with local hosts adopted new linguistic and behavioural patterns, whereas those who could not adjust were called ‘loiterers’ because of their visibly distinct behaviour and were considered a security threat. They were more likely to return to their home countries.

Resilience to incarceration stress

Incarceration stress appeared to be the most challenging for terrorists. In previous research, terrorists contended that torture in prisons led to mental illness and suicide due to suffering; thus, they preferred to be killed rather than captured. Osama bin Laden criticised such an attitude as he believed that capture could be avoided with proper behaviour modifications.

Al-Qaeda tried to improve resilience to incarceration stress through conducting captive training, maintaining communication with imprisoned members, paying a ransom to release them, and financially supporting their family members. While in prison, al-Qaeda members were encouraged to use their time for self-reflection and to strengthen themselves with faith.

Prison programmes that aimed to ‘deradicalise’ and ‘disengage’ terrorists appeared futile, at least in Egypt, Libya, and Saudi Arabia, as al-Qaeda members either tried to deceive the authorities through abiding by conditions of programmes to be released or openly opposed such programmes. Once released, most members returned to terrorist activity.

Implications

Al-Qaeda builds its resilience to stress through the skilful management of human resources to accurately match personalities with operational responsibilities and the harnessing of social structures and support, such as family and comrade relationships and senior-youth mentorship, through which intergenerational transmission of terrorist goals and experiences persists.

These findings are important to consider when planning counterterrorism operations such as intelligence collection, infiltration into terrorist groups, as well as desistance and disengagement interventions for incarcerated terrorists.

Counterterrorism interventions need to continue dismantling al-Qaeda’s ideology that underlies its resilience.

Al-Qaeda’s extreme faith-based political ideology serves as a framework that underpins the major components of its resilience. However, as previous research on how terrorism ends showed, religious terrorist organisations survive longer but they never win. This inability to win stems from al-Qaeda’s lack of insight into the fact that its ideology is dystopian and its goals are unachievable in a modern world.

Being resilient does not necessarily help terrorists to achieve their political goals, but it retains their functional capacity to unceasingly threaten public safety. Disrupting intergenerational transmission of resilience in terrorists would require developing disengagement interventions, specifically, for children of terrorists.

Future research is needed to investigate the possibility and ways of integration of children of terrorists into society. Both Hamza and Saad bin Laden named their sons after their father, Osama, hoping that they will carry on in his path; disrupting this transmission to yet another generation remains a challenge.

Read more

- Ananda Amstadter, Arden Moscati, Hermine H. Maes, John M. Myers, and Kenneth S. Kendler. 2016. ‘Personality, Cognitive/Psychological Traits and Psychiatric Resilience: A Multivariate Twin Study’. Personality and Individual Differences 91 (March): 74–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.041

- Martha Crenshaw and Gary LaFree. 2016. Countering Terrorism: No Simple Solutions. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press

- Paul Gill and Emily Corner. 2017. ‘There and Back Again: The Study of Mental Disorder and Terrorist Involvement’. The American Psychologist 72 (3): 231–41. Available at: https://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/releases/amp-amp0000090.pdf

- Emma Grace. 2018a. ‘A Dangerous Science: Psychology in Al Qaeda’s Words’. Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict 11 (1): 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/17467586.2018.1428762

- ———. 2018b. ‘Lex Talionis in the Twenty-First Century: Revenge Ideation and Terrorism’. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression 10 (3): 249–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2018.1428660

- Atsushi Oshio, Kanako Taku, Mari Hirano, and Gul Saeed. 2018. ‘Resilience and Big Five Personality Traits: A Meta-Analysis’. Personality and Individual Differences 127 (June): 54–60. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323218918_Resilience_and_Big_Five_Personality_Traits_A_meta-analysis

- Ali Soufan. 2017. ‘Hamza Bin Ladin: From Steadfast Son to Al-Qa`ida’s Leader in Waiting’. CTC Sentinel 10 (8). https://ctc.usma.edu/hamza-bin-ladin-from-steadfast-son-to-al-qaidas-leader-in-waiting/

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.