Debates about violent extremism (especially jihadist and far-right varieties) often focus on the role of religious belief or political ideology, or both, in motivating the perpetrators. Yet acts of mass public violence are not solely carried out by explicitly religious or political actors. ‘Dark fandoms’ (groups that are fascinated by people and events central to an act of violence or atrocity) have also added to public concerns about copycat violence.

One paradigmatic example of a ‘dark fandom’ is the online communities dedicated to Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, the perpetrators of the 1999 Columbine High School shooting. Earlier studies of ‘Columbiners’ tended to portray them as deviants, whose admiration for Harris and Klebold was equated with approval of their violent acts.

According to more recent research, however, many fans may have empathised with the bullying (real or purported) experienced by Harris and Klebold, but stopped short of condoning their actions. In other words, dark fandoms are not straightforward incubators of violence — they attract different types and degrees of interest.

Dark fandoms can help us understand how copycat violence can be influenced by three overlapping factors — identification with role models, the intersections of ideological content and practical tactics, and the dynamics of online and offline interactions.

Role models

On the one hand, fascination with particular individuals is by itself not a sufficient indicator of the potential for copycat violence. This is true of the Columbiner fans who express empathy for Harris and Klebold whilst not condoning their actions. This ambivalence is also present amongst ‘Aumers’ — fans of Aum Shinrikyo, the Japanese new religious movement responsible for several violent crimes including the deadly 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway.

On the other hand, adulation of Harris and Klebold was clearly present amongst Lindsay Souvannarath and James Gamble, the would-be perpetrators of the foiled 2015 Valentine’s Day plot in Nova Scotia, Canada. But, crucially, Souvannarath and Gamble also condoned the actions of Harris and Klebold and wanted to emulate them.

“True” copycats can thus be understood as perpetrators who seek to reproduce the original recipe as closely as possible.

Ideology and tactics

To use a cookbook analogy: recipes can be followed closely, or they can be improvised and changed. ‘True’ copycats can thus be understood as perpetrators who seek to reproduce the original recipe as closely as possible.

In the case of the foiled Valentine’s Day plot, two aspects of the original recipe help to identify Souvannarath and Gamble as ‘true’ copycats — their personal adulation for the shooters and the conscious desire to emulate their methods. Souvannarath and Gamble also shared the shooters’ disdain for white middle-class, suburban lifestyles and values. Agreement with the perpetrator’s beliefs, which can sometimes be expressed implicitly, is therefore another necessary ingredient that defines copycat violence.

Different combinations of these factors can produce different variants of copycat violence. Harris and Klebold, for example, were partly inspired by the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995. According to their diaries, they wanted to exceed its death toll.

Meanwhile, Timothy McVeigh (the Oklahoma City bomber) was partly motivated by vengeance for the Waco Siege of 1993, during which the actions of US enforcement agencies triggered a series of confrontations that culminated in the deaths of 76 members of a millenarian movement. This explicit vengeance against the US state was absent for the Columbine shooters. McVeigh can therefore be seen as an avenger, a description that does not quite apply to Harris and Klebold. If anything, they drew inspiration from McVeigh’s tactics rather than his ideology.

Setting

The foiled Valentine’s Day plot illustrates how online and offline settings influenced Souvannarath’s trajectory. After graduating from college in 2014, she started forming friendships only online, where she met and forged a relationship with Gamble through Columbiner networks. The pair began plotting on social media and eventually met in person to carry out their attack before it was stopped by the police.

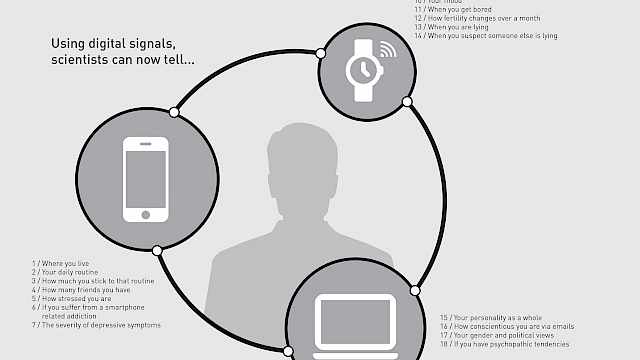

Souvannarath’s journey raises questions about the extent to which online environments provide cognitive openings for radicalisation. Also, do they create a separate-but-parallel virtual reality or an extension of an individual’s social reality? Do they encourage aggression by facilitating anonymity?

Meanwhile, it is unclear whether several of the copycats inspired by the Norwegian far-right terrorist Anders Breivik actually belonged to any online or offline communities. We must therefore question if online or offline forums are a necessary or sufficient factor in the making of copycat violence.

Effectively identifying different routes towards violent extremism, therefore, requires us to discern the nuances in how people relate to violent perpetrators, their actions, and their motivations in different settings. Online ‘dark fandoms’ are an important phenomenon to develop better understandings of the distinct and varied ways individuals and groups respond to violent atrocities.

Dr Shanon Shah is a tutor in Interfaith Relations at the University of London’s Divinity programme and a researcher at Inform, based at King’s College London. His research focuses on social justice trends in contemporary Islam and Christianity, and the intersections of esoteric religious movements and political action.

Read more

Bangstad, S. (2021). What has Norway learned from the Utøya attack 10 years ago? Not what I hoped. The Guardian. https://bit.ly/3pfqtMo

Berger, J. M. (2019). The Dangerous Spread of Extremist Manifestos. The Atlantic. https://bit.ly/36zvxol

Gill, P. (2012). Tracing the Motivations and Antecedent Behaviors of Lone-Actor Terrorism: A Routine Activity Analysis of Five Lone-Actor Terrorist Events. International Center for the Study of Terrorism. https://bit.ly/3JQOeCs

Lamoureux, M. (2019). The Woman Who Plotted a Valentine’s Mass Murder Shares How the Internet Radicalized Her. Vice. https://bit.ly/3peXnga

Monroe, R. (2019). The cult of Columbine: how an obsession with school shooters led to a murder plot. The Guardian. https://bit.ly/33QMwS9

Osaki, T. (2014). Aum cultists inspire a new generation of admirers. The Japan Times. https://bit.ly/3sifhR4

Vidal, G. (2008). The Meaning of Timothy McVeigh. Vanity Fair. https://bit.ly/3t4KpD2

Wright, B. L. (2019). Don’t fear the nobodies: A critical youth study of the Columbiner Instagram community. Mississippi State University. https://bit.ly/3JYCmOV

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)