On December 11, 2017, I was considerably late for my shift at a clinic for individuals with chronic mental illness. As many other New Yorkers that day, my morning commute had turned into an anxious, long, underground wait as train traffic throughout the city froze in response to reports of a pipe bomb detonating in a subway station near Midtown Manhattan. Eventually, the threat was ‘contained’, and the daily New York grind resumed, but with a backdrop of rumours, unverified facts, and heightened tension. This tension remained when I walked into the therapy group I facilitated for patients with command hallucinations - people who hear voices telling them what to do.

I had always enjoyed the lively discussions in this ‘voices’ group, which showcased the patients’ resilience and good humour. The group was a safe space where participants could share comments such as: “The voices were back this morning and kept telling me to jump out the window. As if I would ever do such a thing. As if I was crazy or something!”. But the atmosphere in the group was bleak that December 11. A patient addressed the source of the tension: “It is just a matter of time before they claim the bomber was mentally ill. They always bring mental illness into it. I am not dangerous. I have never hurt anybody.”

The group then shared stories about facing discrimination and of being feared and misunderstood. That day, humour was replaced with a frank discussion about the toll of stigma towards mental illness on the quality of my group members’ lives. Patients shared how the stigma the group experienced tended to spike in the wake of school shootings, terrorist attacks or any other incident where media coverage of a violent event included a discussion of mental illness.

I am frequently reminded of that day’s group session as I join and encourage the many voices calling for integration of Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) into peacebuilding and into efforts to prevent and address extremism. I hang on to the memory as a cautionary tale, and as an invitation to think about how to speak fairly about the relationship between trauma, mental illness, and violent extremism without unjustly increasing stigma and discrimination against people who, as my patient said, “have never hurt anybody”. How do we toe this line responsibly?

1. We responsibly address the relationship between mental illness, adversity and violent extremism by avoiding generalisations.

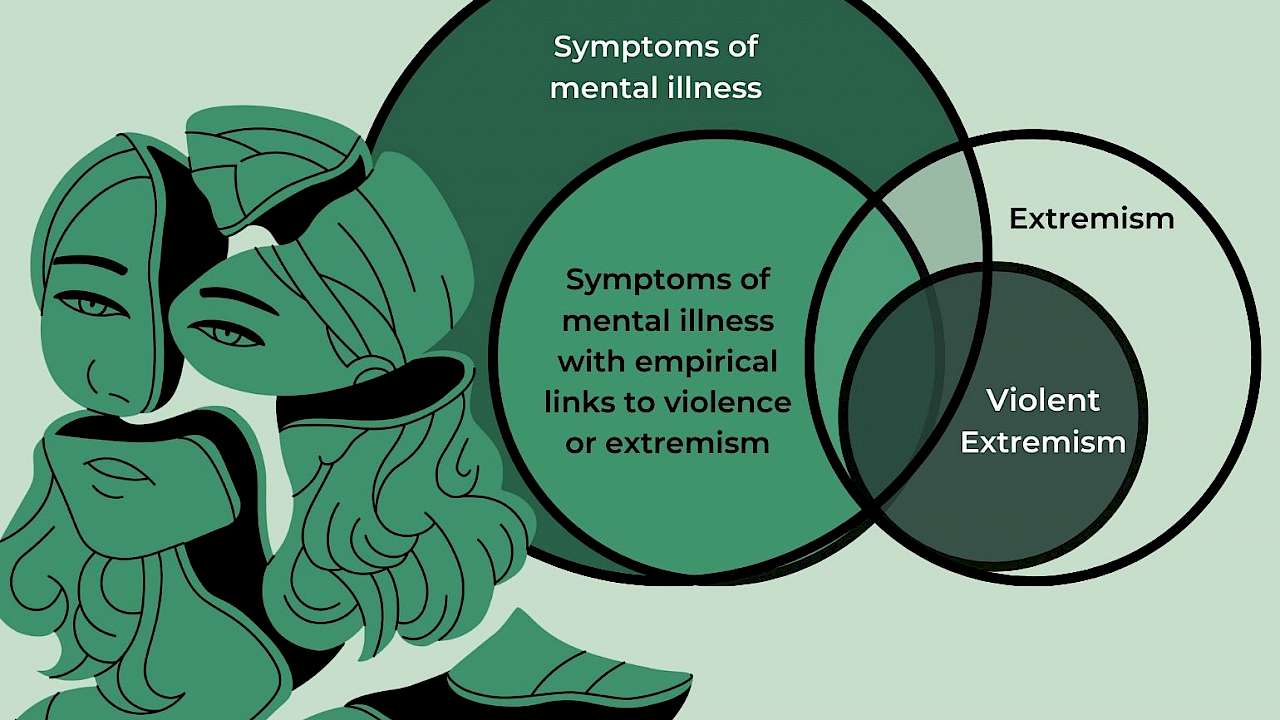

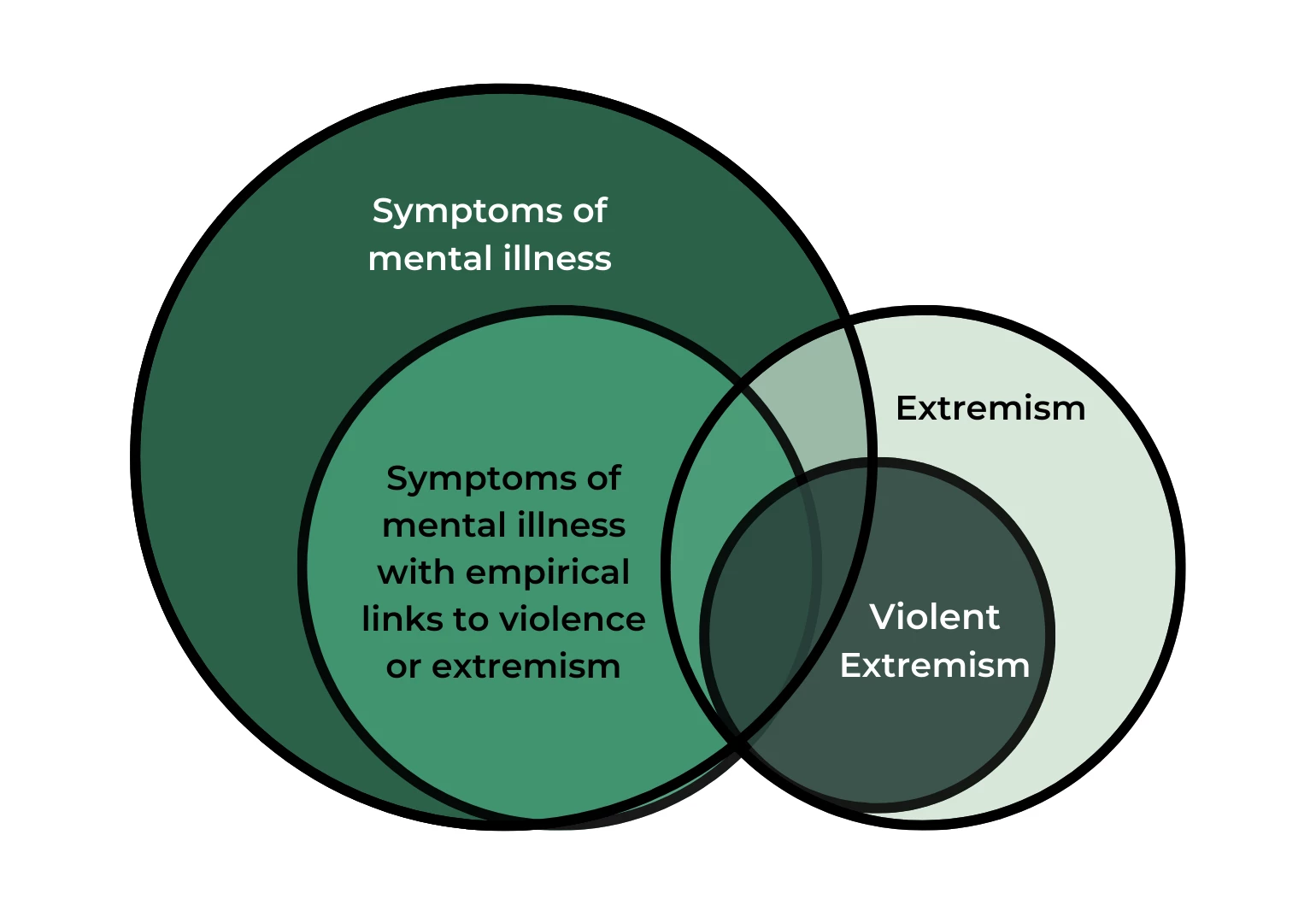

It will always bear repeating that there is no empirical evidence in support of a direct causal link between mental illness and violent extremism. This message is particularly important to convey with clarity when addressing new collaborators or stakeholders. Failure to properly clarify this message can potentially result in harmful generalisations wherein any sign of mental illness or distress is interpreted and approached as a risk factor for violent extremism. I personally find Venn diagrams helpful in clarifying the following points to newer audiences:

- The circle of mental health symptoms contains a smaller circle of symptoms with empirical or theoretical ties to violence or to extremism. Not all symptoms or mental health pathology have a relation to violence or extremism.

- The circle containing people with extremist views contains a smaller circle of violent extremism. Not all people with extremist views are motivated to act violently in support of these views.

- There is only partial overlap between the extremism and mental illness circles. It is possible to have symptoms of mental illness - including symptoms with empirical links to extremism or violence- and not be an extremist. It is also possible to be an extremist without having any symptoms of mental illness.

- The overlap between the extremism and mental illness circles includes symptoms with no empirical or theoretical ties to extremism. It is possible to be an extremist or a violent extremist with symptoms of mental illness that are unrelated and unconnected to either violence or extremism.

- Trauma and adversity neither contain nor are contained by any of the above circles. Extremism and mental illness can both occur without trauma and adversity, can be a consequence of trauma and adversity, or can lead to trauma and adversity.

Naturally, after outlining the significant and important limitations of the relationship between mental illness, adversity and extremism, one might be left wondering why an effort to integrate MHPSS into violent extremism prevention is relevant or worth pursuing to begin with. This brings us to a second important way in which we address this relationship responsibly:

2. We address the relationship between mental illness, adversity and violent extremism responsibly by adding nuance and a deeper understanding of where exactly the connection lies.

Just as Venn diagrams can help clarify the need to tread carefully and not generalise when presenting a connection between radicalisation and mental illness, plots of normal distributions can help us understand one fundamental similarity between extremism and mental illness. That is – mental health pathology and radicalised thinking are both defined by relative comparison to what is normative within a society at a given time. They are both less frequent and more extreme thoughts or behaviours. They are both far ends and margins of a normal distribution curve.

Which behaviour is deemed pathological and which belief is deemed extreme can vary from region to region and from decade to decade. The common thread is simply that all human behaviours, attitudes and preferences fall within a normally distributed continuum and our society always sets the standard that dictates what level of deviation from a given norm is acceptable, what level of deviation warrants a reward, and what level of deviation warrants punishment. For example, from a mental health perspective, we might praise and reward upper-end deviations in intelligence but reject and marginalise lower-end deviations in emotion regulation that result in awkward outbursts or in failure to abide by societal rules.

At the same time, from a thoughts and ideas perspective, we might praise some deviations from the norm by labelling them as ‘artistic’, ‘provocative’ or ‘forward thinking’, and we might punish and exclude other deviations as ‘dangerous’, ‘obsolete’, or ‘extreme’.

The common thread is simply that all human behaviours, attitudes and preferences fall within a normally distributed continuum and our society always sets the standard that dictates what level of deviation from a given norm is acceptable.

Considerable effort is spent pursuing a deeper understanding of the etiology of radical thinking. While this information is valuable, we must also remember that, probabilistically speaking, all behaviours and thoughts will always tend to be normally distributed within groups: there will be extremes within any group and society.

However, as a society, we can be motivated to modify our responses to said extremes once we understand the impact of our responses. Let us consider, for example, how a community’s readiness to provide mental health support plays a key role in determining how costly pathology is after adversity:

If an individual who experienced a traumatic event became depressed or showed signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and the community was intolerant of the ensuing ‘extreme’ behaviour, then the individual would be marginalised and rejected. They might lose their job, social connections, and support network. Even after the pathology is resolved and their behaviour returned to what would be considered normal and acceptable, the individual would then continue to face consequences that outlast the pathology. In this example, adversity resulted in pathology and in turn, pathology became a new source of adversity. Further, the individual’s rejection by the community due to mental health stigma could result in a series of obstacles and challenges that are well-documented push and pull factors linked to violent extremism.

A discussion of the connection between adversity, mental illness and violent extremism is, at its core, a discussion of marginalisation and the erosion of the societal protective factors that could help prevent violent extremism.

While, as was previously discussed, there is no direct causal connection between mental illness and extremism, they both potentially place individuals at the extreme ends of a curve of normative and acceptable behaviour and thought. This can potentially have costly consequences in terms of loss of social support and role. A discussion of the connection between adversity, mental illness and violent extremism is, at its core, a discussion of marginalisation and the erosion of the societal protective factors that could help prevent violent extremism.

3. We address the relationship between mental illness and violent extremism responsibly by doing no harm.

It is at the common space of marginalisation shared by extremism and mental illness that the integration of MHPSS into the prevention of violent extremism becomes most relevant. This is not because MHPSS will prevent pathology, but rather, it is relevant insofar as it allows communities to respond differently to deviation, decreasing rather than increasing adversity and risk factors.

Returning to our example of the individual facing depression or PTSD after living through a traumatic experience, if instead of responding with mental health stigma and rejection, the community understood what was happening to the person and was able to make space to tolerate their out-of-norm behaviour and support them, that individual would then likely be able to restore their former role and status within the community once the pathology resolved.

As MHPSS integration into violence prevention continues to grow in popularity, so too will initiatives to provide mental health services to individuals deemed to be at risk of violence or radicalisation. From a do-no-harm perspective, we should encourage caution in rushing to intervene on signalled-out individuals in an attempt to curve certain undesirable behaviours. Instead, MHPSS integration should look first at communities and communities’ tolerance of pathology.

Through the integration of MHPSS into violent extremism prevention, we should aim to increase a community’s ability to understand and recognise potential reactions to adversity and potential signs of mental health distress in a trauma-informed way that fosters connection and tolerance between community members.

Vivian Khedari DePierro, PhD is the Chief Psychologist & Director of Research at Beyond Conflict. As a Clinical Psychologist, she focuses on the development and evaluation of accessible and culturally-tailored approaches to trauma recovery among communities affected by violence and conflict across the globe.

Read more

Al-Attar, Z. (2019). Extremism, Radicalisation & Mental Health: Handbook for Practitioners. Migration and Home Affairs. https://tinyurl.com/b2ud5pj9

Migration and Home Affairs. RAN Mental Health Working Group (RAN HEALTH). https://tinyurl.com/5n854jha

Nir, S. M., & Rashbaum, W. K. (2021). Bomber Strikes Near Times Square, Disrupting City but Killing None. The New York Times. https://tinyurl.com/38ncbx5n

UNDP (2022) Integrating Mental Health and Psychosocial Support into Peacebuilding. United Nations Development Programme. https://tinyurl.com/mtwnk5xc

Copyright Information

Good Studio | shutterstock.com