Imagine being a freshly minted investigative interviewer about to enter an interview with a suspect. As you enter the interview, you wonder how best to frame the interaction. Should you limit the discussion to the facts only? Perhaps it might be better to explore the suspect’s feelings and worries about their future? What about trying to be friends and crack some jokes to make them feel better? The answer to these questions is not simple. Recent research on interpersonal sensemaking in investigative interviews can offer some insights.

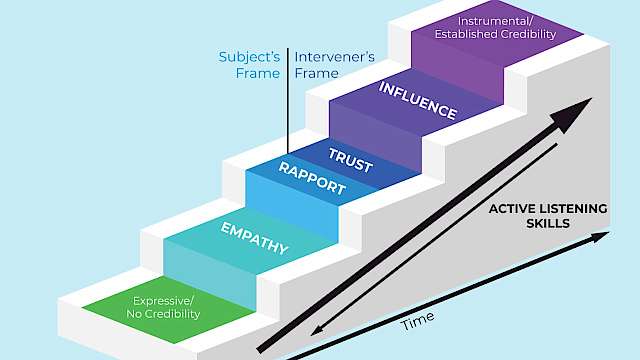

Used by investigative interviewing and crisis negotiation teams around the world, interpersonal sensemaking is a framework for understanding the way people communicate and the goals and motivations that underlie those ways (Taylor, 2014). At any one point in time, suspects tend to focus their goals and motivations around instrumental (facts and information), relational (establishing or breaking down the relationship with their interviewer), or identity (personal needs and wants) issues (Taylor, 2002).

In my PhD research together with my supervisors at Lancaster University, we have been investigating (i), how to successfully develop interpersonal sensemaking in investigative interviews through matching (i.e., coordination) of these motivations, and (ii), what consequences it has on interview outcomes and reciprocal matching. This is what we have found.

...suspects who interacted with an interviewer who consistently made sense of their goals and motivations were more willing to cooperate and felt more understood compared to those whose interviewer did not make sense of them (i.e., did not match their motivations)

Matching of motivation is key

Across several experiments, involving hundreds of participants, we have found that focusing on similar issues, (i.e., motivational matching) consistently led to more positive investigative interview outcomes (Sjöberg et al., 2023). In other words, suspects who interacted with an interviewer who consistently made sense of their goals and motivations were more willing to cooperate and felt more understood compared to those whose interviewer did not make sense of them (i.e., did not match their motivations). Besides, they were often more willing to trust them. Hence, successful interpersonal sensemaking might be a shortcut to building trust and positive working relationships.

Interestingly, suspects who interacted with an interviewer who made sense of their goals through motivational matching also displayed more reciprocal motivational matching. That is, they increasingly started to match the interviewer’s goals and motivations back. This constitutes a form of entrainment, where the interviewer’s adjustment on the motivational frames leads to similar, synchronised changes in the suspect’s motivations (Wells & Brandon, 2019).

As an investigative interviewer, making sense of a suspect’s goals and motivations is likely important. For example, asking for meticulous details about the suspect’s whereabouts while they voice concern about the wellbeing of their friends and family might not be the best strategy. Why? The question is focused on an instrumental goal while the suspect’s needs are rooted in their worries about their friends and family (identity motivations). Getting into the same frame as the suspect is the first step in starting to understand their wants and needs and how to best address them. Hence, being able to identify a suspect’s goals and motivations and then matching those, ought to be an important skill for any investigative interviewer worthy of their craft.

Is matching always positive?

It is easy to assume that motivational matching works under any circumstance. However, there are situations when matching can backfire. For example, in our experiments, we have found that when the investigative interviewer and suspect were arguing with each other (they were both in a competitive orientation), motivational matching generally led to worse interview outcomes. More interestingly, this was particularly true when they were attacking each other’s identity or the relationship they had with each other (i.e., identity and relational matching), rather than focusing exclusively on the problem (i.e., instrumental matching).

...when the investigative interviewer and suspect were arguing with each other (they were both in a competitive orientation), motivational matching generally led to worse interview outcomes.

This has potential implications for investigative interviewers. In essence, if you absolutely must argue with someone, it is probably wise to strive to keep the conversation on topic. At all costs, avoid reciprocating negative behaviours such as ridicule or personal insults, as these might force the interview down a negative spiral of conflict and stalemate.

In a complex social interaction such as an investigative interview, failure to accurately plan and prepare could be costly. Interpersonal sensemaking in general, and motivational frame matching in particular, may offer a simple framework for starting to help make sense of conversations with suspects. This, in turn, may constitute the first building blocks to establishing a relationship with them that can eventually promote cooperation and trust.

Read more

Sjöberg, M., Taylor, P. J., Conchie, S. M. (2023). The cylinder model. In G. Oxburgh et al. (Eds.), Interviewing and interrogation: A review of research and practice since World War II. Florence, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher.

Taylor, P. J. (2002). A cylindrical model of communication behavior in crisis negotiations. Human Communication Research, 28(1), 7-48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00797.x

Taylor, P. J. (2014). The role of language in conflict and conflict resolution. In T. M. Holtgraves (Ed.), The oxford handbook of language and social psychology (pp. 459-470). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wells, S., & Brandon, S. E. (2019). Interviewing in criminal and intelligence-gathering contexts: Applying science. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 18(1), 50-65. https://doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2018.1536090

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)