The Problem

Public sector innovation is needed to tackle the big challenges we face as a society – how to keep people safe, protect the vulnerable, and create a fair and just world in an ever-changing socio-techno-political-geographic context. It relies on the ‘triple helix’ of industry, academia and government working together to create solutions. All too often, innovation fails because of poor inter-relationships between different stakeholders – in this case, we are focusing on civil servants and academics. This article argues that better mutual understanding and adapting accordingly would improve the translation of research and evidence into innovative public policy – ultimately, making a positive difference for us all.

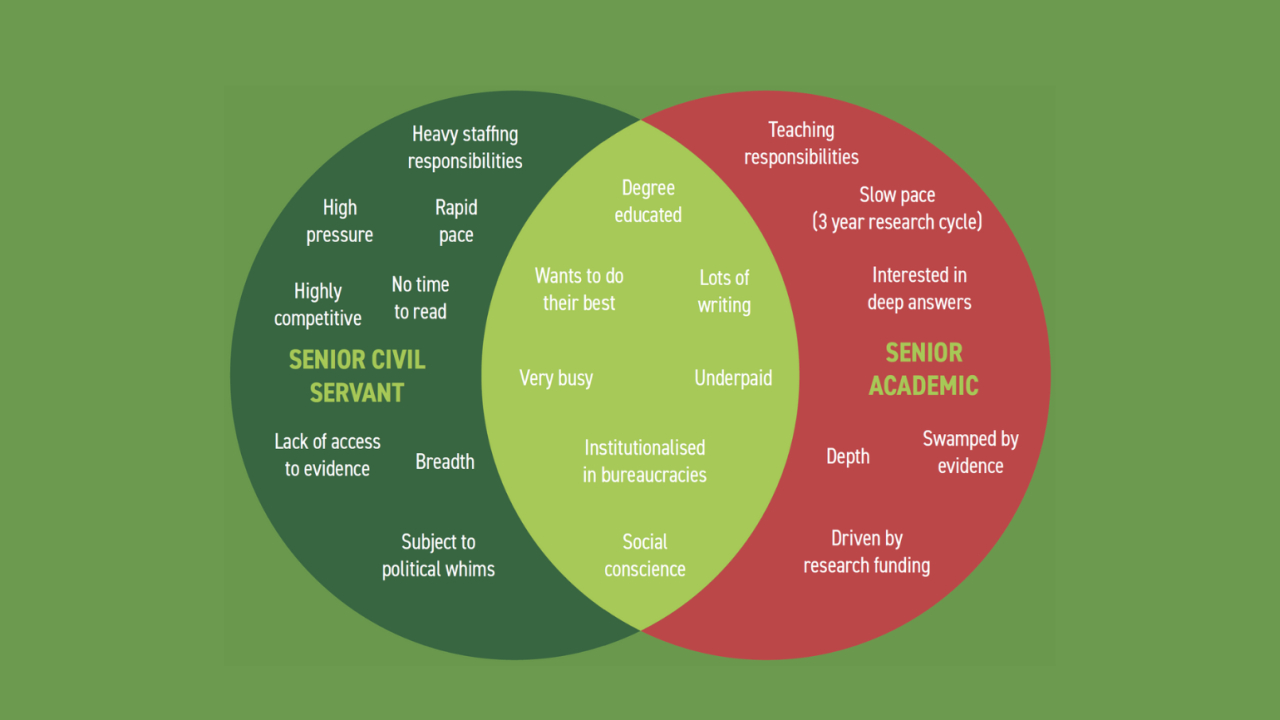

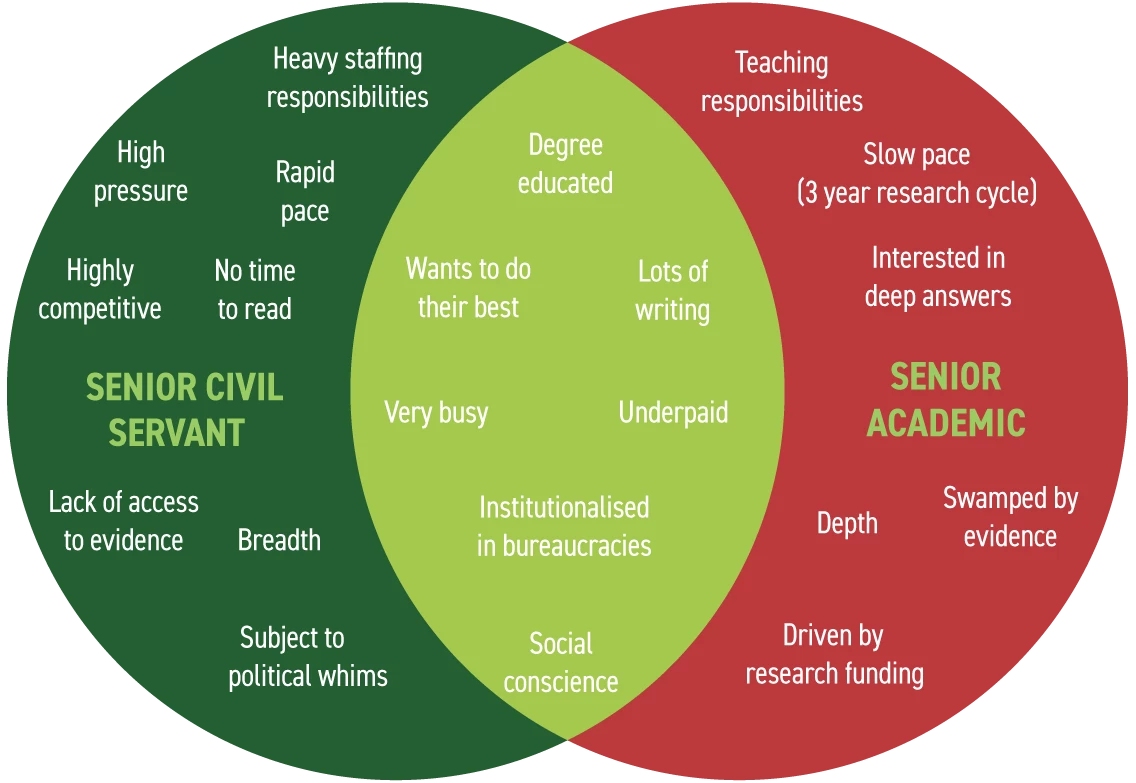

Civil servants and academics have considerable overlap in the types of people who choose those careers – usually degree-educated, and with a passion for doing good in the world (social conscience) which has deterred them from seeking greater riches in industry. But the career pathways in each sector funnel people into ways of thinking and acting, certainly by the time people have reached senior roles – which can lead to a communication and cultural divide – rather crudely characterised in the Venn diagram.

Without wishing to be stereotypical (for of course every institution contains a rich diversity of people and for every rule there is an exception), civil servants are often working at great pace under huge pressure, with goals constantly moving and many stakeholders with often conflicting views. They don’t have the time for slow contemplation, deep reading around their policy area, or to get ‘out and about’ to meet and build personal networks and connections with academics. They don’t read peer-reviewed academic journals, which are often hidden behind paywalls. Often generalists, they have ‘breadth’ rather than ‘depth’. Academics do of course lead busy lives under pressure, but I would argue to a very different extent to most civil servants working in Central Government policy departments. Academics have usually chosen a field they are fascinated by and spend their time (often many years) developing and keeping current a great depth of knowledge. Obviously, accessing this knowledge benefits public policy making. And yet, despite years of Governments’ promising ‘evidence based’ policymaking, this often fails.

Why does research and evidence fail to influence policy as it should?

In many ways civil servants and academics simply speak different languages. They operate in organisational cultures which operate with a very different pace, set of cultural norms, funding routes, priorities, and approaches. So different, in fact, as to be incompatible in some ways: a civil servant might have an afternoon, or a day, or just hours, to draft a policy paper for a minister but an academic asked for an opinion might want weeks or months to provide a properly considered and fully referenced response. A civil servant briefing to a minister needs to be succinct, clear, and helpful in offering tangible advice on what to do: an academic paper is typically densely written, highly nuanced and often using very specific (often contested) terminologies. A civil servant developing policy needs to consider not only the evidence base (often lacking for emerging policy areas, by the very nature of trying to do ‘new’ things) but also what interest groups want, what the public might accept, how the media might engage with the issue, and what might be uppermost in the Minister’s mind. A perfectly sensible policy decision can easily be derailed by a Twitter storm that morning. In contrast academic research is much less susceptible to the ebbs and flows of public discourse and has the luxury of being more purist in its approach to what is and is not good information – but also the disbenefits of having far too much research to get to grips with.

The Solution(s)

In my career, I have taken a very people-orientated approach to public sector innovation, arguing that it is about people and culture much more than systems and processes. This lens is not often applied but offers a truly transformational approach. Behavioural science insights and human-centred research is key to this understanding – as applied effectively during the response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on my work across and within the civil service, academia and private sector, I’d suggest the following advice helps us focus on the people within the systems:

| Civil Servants | Academics |

|---|---|

|

|

Both sides need to spend more time talking to one another, not only about specific research topics but about their cultures, incentives, and pressures, and listening to the other. It’s not simply a question of one side fitting themselves around the other: both sectors need to meet in the middle, and that means challenging some of the ways things are done now. That might mean new kinds of academic roles – ones which have time set aside to build capacity for short turnaround projects for rapid response and building a flexible national capability. It might mean new kinds of civil service roles, specifically targeting external engagement and getting value out of networking, not as a side hustle. And both need to invest seriously in a long-term strategy for training and skills development, for a diverse pipeline of talent who are recognised experts at collaboration (which is a skillset in its own right).

Next Steps

Innovation is all about people. The difference between success or failure depends on what different people wake up and decide to do with their day. And especially now, when innovation requires collaboration between many different stakeholders working together as a (often virtual) team, innovation needs the right conditions to flourish. As a lifelong practitioner of public sector innovation – first as a civil servant, now as a private sector consultant – I’m convinced many of the challenges can be solved by getting people to work better together.

This article is the author’s opinion and does not represent Capgemini Invent.

Read more

Bason, C., 2018. Leading public sector innovation: Co-creating for a better society. Policy press.

Bavel, J.J.V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P.S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M.J., Crum, A.J., Douglas, K.M., Druckman, J.N. and Drury, J., 2020. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature human behaviour, 4(5), pp.460-471.

Cinar, E., Trott, P. and Simms, C., 2019. A systematic review of barriers to public sector innovation process. Public Management Review, 21(2), pp.264-290.

Galvao, A., Mascarenhas, C., Marques, C., Ferreira, J. and Ratten, V., 2019. Triple helix and its evolution: a systematic literature review. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management.

Mason, L., Shortland, A. (2022) National Security Innovation: Creating new capabilities for the future, CETaS Expert Analysis https://cetas.turing.ac.uk/publications/national-security-innovation-creating-new-capabilities-future

Neil Reeder (2020) Organizational culture and career development in the British civil service, Public Money & Management, 40:8, 559 568, DOI: 10.1080/09540962.2020.1754576

POSTnote. (n.d.). UK Parliament. https://post.parliament.uk/type/postnote/

S, A., Killworth, P. (2022) Reinventing National Security: Innovation, Diversity and Inclusion, CETaS Expert Analysis https://cetas.turing.ac.uk/publications/reinventing-national-security-innovation-diversity-and-inclusion

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)