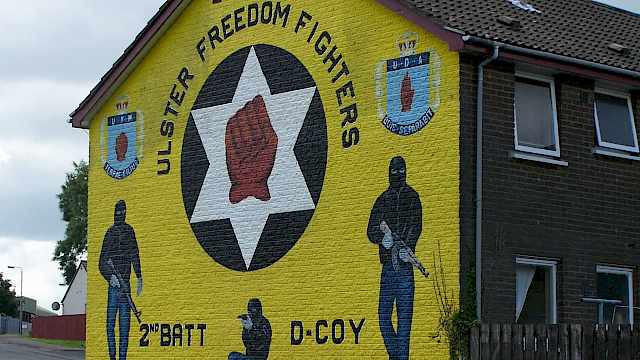

When analysing the transmission of violent dissident Irish republican (VDR) ideas, beliefs and values, the central question is how do they transmit an air of legitimacy for the continuation of their armed campaign? Their former comrades in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) have now completely politicised. The peace process has seen almost two decades of relative peace and prosperity in the region. The vast majority of the Northern Irish population, irrespective of political beliefs, condemn any return to violence. Yet, there remain those who wish to maintain paramilitary activity in order to, ostensibly, achieve a united Ireland.

The challenge to develop and transmit legitimacy is internally acknowledged as the most significant obstacle they must overcome. For years the VDR community has been an assortment of groups, each carrying its own unique acronym and claims of legitimacy. Their potential support base consistently turned its back on them, even if it was unwilling to support Sinn Fein and the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement. Without this support, it was close to impossible for VDR groups to maintain any significant foothold, or progress in any way. Consequently, one of the dominant narratives in VDR statements over recent years has been the call for anti-Good Friday Agreement Republican unity. In 2012, this introspection of dissidence led to the formation of the VDR merger under the self-aggrandising moniker of ‘The IRA.’ Since then, ‘The IRA’ (hereafter ‘IRA/New IRA’) has attempted to demonstrate that it is the only force able to challenge the republican supremacy of Sinn Fein and the perceived oppression by the British ‘occupying force.’

Central to the VDR quest for legitimacy has been the emphasis of the plight of their prisoner community. Invoking the memory of Bobby Sands and others, they depict the VDR prisoners as the victims of an oppressive judicial system and prison regime. This has manifested in the proliferation of prisoner statements reinforcing the notion of apparent victimisation. This has seen the more persistent targeting of prison officers in order to further emphasise the centrality of the prisoners’ struggle to their legitimising campaign. The 2012 murder of David Black and 2016 murder of Adrian Ismay are stark illustrations of this.

For supporters of the peace process, it is imperative that no opportunity is given to the VDR groups to legitimise their narrative of victimisation, in the prisons or across the criminal justice system. The publication of a damning report in 2015 of the conditions and operations within Maghaberry prison was seized upon by prisoners and their external representatives as evidence of their targeted victimisation by a corrupt and inhumane prison regime. It is only if VDR groups succeed in depicting republicans and nationalists as victims that they will achieve any significant level of support.

In their minds it was only the prisoner population who could bestow the necessary legitimacy. With this power comes a glimmer of opportunity.

The highlighting of the prisoners’ cause provides one of the fundamental ways in which the IRA/New IRA differentiate themselves in the competition for support in the face of the fully politicised Sinn Fein. The persistent narrative is that, in their embrace of ‘constitutional nationalism’, Sinn Fein has abandoned the IRA oath, constitution and the prisoner population. No longer is Sinn Fein the representative of the republican working class or those who sacrificed their lives for the republican cause. This is illustrated in the 2016 launch of the new political wing of the IRA/New IRA, Saoradh. Throughout the development of the party, leaders emphasised the support received from prisoners. In their minds, it was only the prisoner population who could bestow the necessary legitimacy. With this power comes a glimmer of opportunity.

During the 1969–97 ‘Troubles’, internal discussions within the republican prisoner population played a significant role in the politicisation of members of PIRA. The potential for similar influence has recently appeared in the prisoner publication, Scairt Amach. Since 2015, articles have appeared questioning the maintenance of paramilitary vigilantism. They question whether the tactic may actually be driving support away, rather than strengthening it. It is only with this internal debate led by trusted members, that an organisation can move away from long-fostered strategies.

Ultimately, efforts to counter the legitimacy of these groups and their violence will only be successful when it comes from those influential within dissident republicanism. It is for this reason that the prisoners’ challenge to the continuation of vigilantism and punishment attacks must be welcomed and supported. It has yet to bear fruit and may provide false hope. Yet it demonstrates the potential for a discussion about the gradual move from violence.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.