Islamophobia is widespread in the UK. A 2015 YouGov poll found that over half of British voters think there is a fundamental clash between the values of Islam and British society.

Despite Islamophobia entering the mainstream, most people who sympathise with it will not participate in protests organised by groups such as the English Defence League (EDL). With such a deep pool of potential participants, why is anti-Muslim protest not more common?

This puzzle can be solved if Islamophobic activism – like other forms of political organisation – is understood as a collective action problem. Because the benefits of political action may be enjoyed by participants and non-participants, whereas the costs are borne by participants alone, it may be in an individual’s self-interest to free-ride on the activism of others rather than directly participate and bear the costs of political activity.

One way in which a political organisation may overcome the collective action problem is through the provision of club goods to participants that cannot be enjoyed by non-participants.

The benefits of action in the EDL

In the case of the EDL, those who engage in organised Islamophobic activism do so because participation brings direct personal benefits that outweigh the personal costs. Throughout 2013/14, I conducted fieldwork with the EDL – I attended a number of EDL demonstrations, ‘meet and greet’ events, and informal pub gatherings, and was added as a member of a closed Facebook group. This original data reveals that the participation of grassroots members was driven by the club goods of access to violent conflict, increased self-worth and group solidarity. These goods are supplied exclusively to EDL members; that is, they could not be obtained other than through EDL participation.

Opportunities for violent conflict

In his study of the EDL, Joel Busher found that 30–40 per cent of EDL members were football hooligans, and notes that physical confrontations with opponents were an essential element of the EDL’s ‘emotional alchemy’.

In research I conducted with John Meadowcroft, we similarly found that a striking feature of the EDL was the important role of violence within the organisation and that participating within the group gave members an opportunity to engage in physical altercations. For example, at a demonstration in the centre of Birmingham in July 2013, numerous scuffles between EDL and Unite Against Fascism counter-protestors were witnessed and a number of EDL members came away bleeding from head wounds. EDL members were observed sniffing and eating a white powder before moving to the front of the demonstration to aggressively taunt police and counter-demonstrators.

Accordingly, we conclude that EDL street protests are likely to appeal to football hooligans because of the opportunities for violent conflict at these events.

The loyal footsoldier

EDL participation also enables members to construct a sense of self-worth that affirms their dignity independently of their low socio-economic status. We found that EDL activism is couched in moral terms – particularly, the duty to protect one’s family and one’s community – that provides its predominantly working-class members with a heightened sense of their own self-worth. For example, during the Birmingham demonstration, one member revealed that he thought his family could be protected by his EDL participation when he stated that ‘ Cameron won’t stand up for us, so we have to stand up; if we don’t stand up, it will be my children, and I’d rather it be me than my children’.

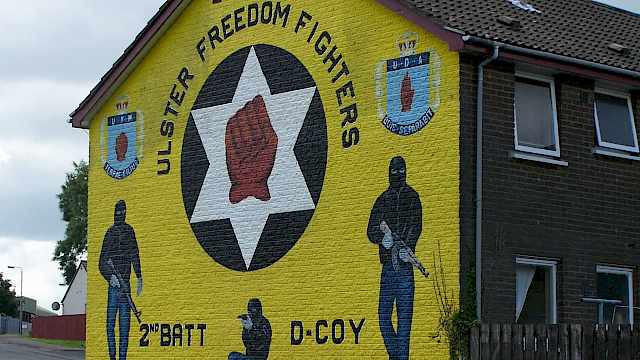

EDL participation is presented as analogous to being a soldier of war

EDL membership also increases self-worth by purportedly providing participants with an opportunity to protect their country. Indeed, EDL participation is presented as analogous to being a soldier of war. The very name ‘English Defence League’ connotes quasi-military action to safeguard the country against Islam. Many EDL members (both men and women) wear branded clothing that states their division, emblazoned with the words, ‘Loyal Footsoldier’.

Group solidarity

The third exclusive benefit that the EDL supplies to its members is group solidarity: the opportunity to be part of a close-knit group united by the belief that they are fighting for a common and just cause. For example, at one meet-and-greet session, an EDL member told the audience that when they go to a demonstration, ‘you go as brothers and sisters’. He talked about getting the coach to an upcoming demonstration and said that when members travel on the coach they ‘are like a family’, and told them ‘you have to respect that you will be travelling as part of a family’.

The costs of EDL activism

As well as the benefits described above, like all political activity, EDL membership also imposes costs, in particular, stigma. Indeed, it is such a stigmatised activity that several members revealed that they had family and friends who privately supported their activism, yet did not want to participate more actively because it might jeopardise their career. One member revealed that although he had managed to persuade his mother that the EDL ‘isn’t bad or racist’, she was unable to ‘support him officially’ because she would lose her job as a teacher if her support became public. The same member also said he did not fear losing his job because he thinks that his managers at the warehouse are supportive of his EDL involvement, yet ‘can’t say so out loud because they’d be sacked’.

This data strongly suggests that EDL sympathisers will not turn to activism if the cost (in this case, job loss) exceeds the benefits to be gained from activism. It is also worth noting that these examples suggest individuals with jobs that place them in the public eye – for example, teachers and managers – are more likely to face employment sanctions than those with less visible occupations.

The benefits of EDL membership will appeal more to those individuals who enjoy violence and aggressive confrontation, have low self-worth and value the group solidarity the EDL offers. Accordingly, it should not be surprising that most EDL members are young men, often with links to football hooliganism, who are employed in industries that are unlikely to sanction them for their involvement.

To understand the appeal of EDL activism, it is not enough to examine the group’s ideological appeal; the costs and benefits of activism must also be identified.

- The views expressed in this article are those of the author and not of CREST.

- Main image (EDL Protest in Newcastle) is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license via Wikimedia Commons. Original photograph by lionheartphotography. Source via Flickr.

Read more

Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action: Publics Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965)

Gordon Tullock, “The Paradox of Revolution”, Public Choice 11, no.1 (1971): 89–99

Joel Busher, The Making of Anti-Muslim Protest: Grassroots Activism in the English Defence League (London: Routledge, 2015), 38, 141

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.