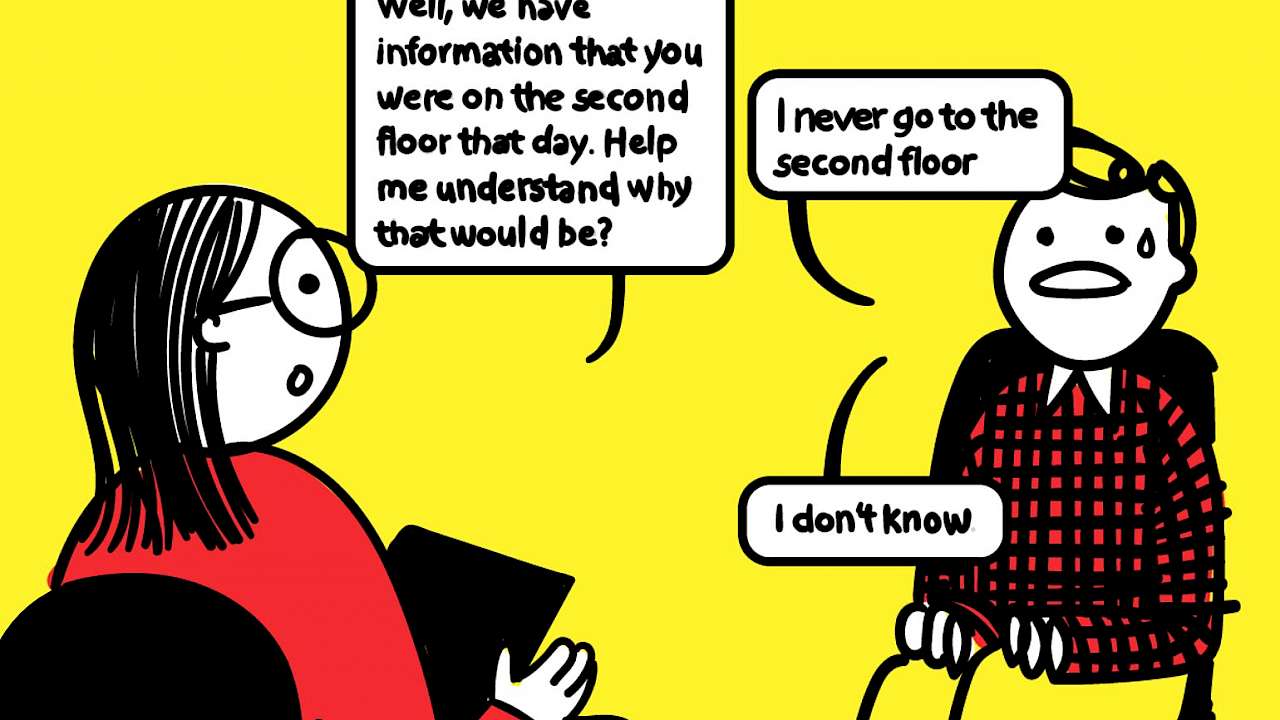

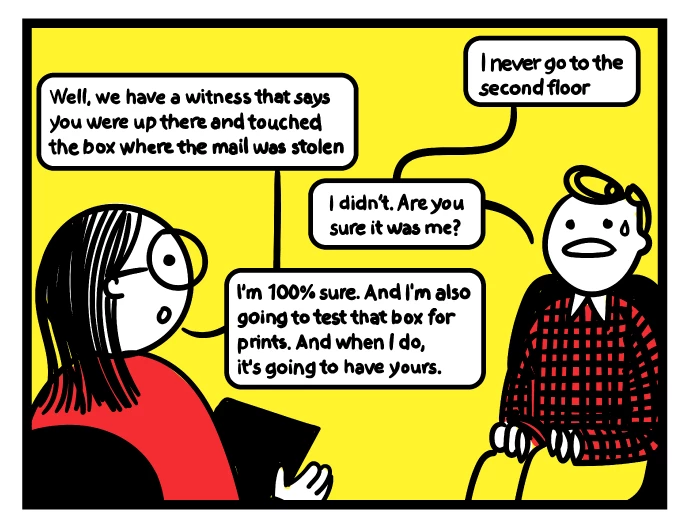

Through our observations of suspect interviews conducted by U.S. law enforcement, we noticed that many interviewers who have gone through previous iterations of science-based interview training follow productive practices, such as rapport-building, active listening, and using appropriate questions. Yet, what they still miss is an effective way of dealing with persistent denials, as these cannot always be resolved by good questioning practices. Our observations suggest that in these situations, interviewers can become frustrated, leading them to exchange productive practices for problematic behaviours, such as in the cartoon strip above.

One way an interviewer can encourage suspects to provide explanations is to present evidence. However, without understanding how and why evidence should be disclosed, it may be disclosed inappropriately. This may result in unnecessary confusion and frustration for both interviewer and suspect, hindering cooperation and damaging the relationship, or even resulting in the suspect falsely confessing to a crime they did not commit.

So how can we help interviewers to use evidence effectively? We suggest two fundamental competences are needed:

- The ability to assess the limitations and reliability of evidence.

- An understanding of how evidence disclosure can assist the broader investigation.

Assessing evidence

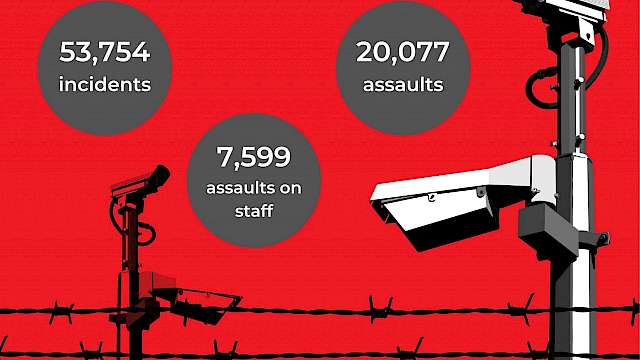

Before disclosing evidence, interviewers need to assess the information already collected and understand limitations associated with physical, technological, and statement evidence. They also need to distinguish available evidence (such as CCTV footage that has been obtained and reviewed) from potential evidence (such as collected DNA that has not yet been processed) and develop initial and competing inferences based only on the available evidence.

An investigative purpose

Evidence disclosure has traditionally been studied with the purpose of enhancing verbal cues to deception and making global veracity assessments. However, although determining a suspect’s credibility can be important for an investigation, it may not always assist in substantiating the facts of the case. Hence, we made it our goal to pinpoint how evidence disclosure contributes to developing a case that could be considered for prosecution.

Evidence is at the heart of any criminal investigation. Put simply, the crime scene investigator identifies, collects, and draws inferences from evidence; the forensic analyst examines evidence; the prosecutor derives narratives from evidence; the defence lawyer critiques the limitations and reliability of evidence; and juries and judges make decisions based on evidence. So how can disclosing evidence in an interview complement these other roles and work to enhance the overall integrity of the investigation?

Proximity-Based Evidence Disclosure

The proximity-based evidence disclosure technique was developed as a way to substantiate the reliability of the available evidence by gradually exploring the suspect’s proximity to the main scene. Interviewers should encourage plausible explanations by:

- Exploring potential links between a subject and each item of evidence;

- Systematically transitioning from disclosing one item of evidence to another.

We therefore developed the Evidence Framing Table (below) to assist interviewers in appropriately framing statements when disclosing evidence. This requires ‘slicing’ the evidence source (from vague to specific) and the evidence proximity (from distant to close), where each slice can be disclosed to explore discrepancies between the suspect’s statements and the available evidence. This table also assists investigators in developing a disclosure order based on each item’s proximity to the main scene.

| SLICE | Frame the Evidence Source | Frame the Evidence Proximity | SLICE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evidence #1: Witness inside mailroom | |||

Vague | We have information that you were... | ... on the second floor. | Distant |

Moderate | Someone matching your description was seen… | ... in the mailroom on the second floor | Moderate |

Specific | There was a person who saw someone matching your description... | ... touching the mailbox in the mailroom on the second floor. | Close |

| Transition into Evidence #2: CCTV footage by the staircase | |||

Vague | We have information that you were holding something... | ... while on the second floor. | Distant |

Moderate | N/A | N/A | Moderate |

Specific | You were seen on CCTV holding an envelope just like the one stolen... | … when leaving the second floor. | Close |

Let us demonstrate how using this technique could improve the interaction in the introductory cartoon strip. By not immediately disclosing all information and instead using the Evidence Framing Table, interviewers can start with placing the suspect at a distant proximity to the evidence. Not only does this allow interviewers to better explore discrepancies and substantiate evidence reliability, but it also encourages them to remain curious and non-judgemental throughout the interview, while offering opportunities to pause evidence disclosure to explore new admissions and mitigate resistance (see the cartoon strip below).

Validation Test

An experiment was used to test the effectiveness of this technique where United States investigators interviewed a mock suspect before and after receiving training. Our findings show that they followed the training, making them:

- Less likely to use problematic techniques, such as leading questions, false evidence ploys, and bluffing.

- More inclined to explore plausible explanations to the available evidence.

- Less likely to gain admissions by using unproductive questions, that diminish their value.

- More likely to gather reliable investigative information.

Final Thoughts

When interviewers are unable to encourage explanations to remaining discrepancies, they can become frustrated, leading them to resort to problematic interview behaviours. Training investigators in ethical and effective evidence disclosure techniques can help reduce these behaviours, but it is important that we make clear how the techniques can work to enhance the integrity of the overall investigation.

Training interviewers to disclose evidence in a way that substantiates its reliability can make them more willing to seek further clarification to the available evidence. It may therefore also provide prosecutors with a more accurate narrative of what might have occurred, and may assist defence lawyers by clarifying how an interviewer is attempting to substantiate whether an item of evidence is reliable or not.

Marika Madfors is a junior researcher at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Netherlands, focusing on appropriate evidence use in investigative interviews.

Dr. Simon Oleszkiewicz is an assistant professor at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

Detective (ret.) Matthew Jones is the founder and lead instructor at Evocavi LLC, a science-based interviewing training company. If you want to know more about the training program, please email: [email protected]

Read more

Dando, C. J., & Bull, R. (2011). Maximising opportunities to detect verbal deception: Training police officers to interview tactically. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 8(2), 189-202. https://tinyurl.com/y6vwuwv2

Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., & Vrij, A. (2005). Detecting deception via strategic disclosure of evidence. Law and Human Behavior, 29(4), 469-484. https://tinyurl.com/mrkykfnj

Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A., Willén, R. M., & Hartwig, M. (2013). Eliciting cues to deception by tactical disclosure of evidence: The first test of the Evidence Framing Matrix. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 18(2), 341-355. https://tinyurl.com/423fpyuk

Meissner, C. A., Kleinman, S. M., Mindthoff, A., Phillips, E. P., & Rothweiler, J. N. (in press) Investigative Interviewing: A Review of the Literature and a Model of Science-Based Practice. Oxford handbook of psychology and law. https://tinyurl.com/yc2ze46m

Oleszkiewicz, S., & Watson, S. J. (2021). A meta‐analytic review of the timing for disclosing evidence when interviewing suspects. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35(2), 342-359. https://tinyurl.com/4fdrt4me

Oleszkiewicz, S., & Granhag, P. A. (2019). Establishing cooperation and eliciting information: Semi-cooperative sources’ affective resistance and cognitive strategies. In The Routledge International Handbook of Legal and Investigative Psychology (pp. 255-267). Routledge. https://tinyurl.com/49snx5hy

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2022 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)