I’ve sat through some mind-numbing, pointless meetings in the course of my working life. I’ve certainly chaired a few! On a couple of occasions, I’ve half-seriously considered breaking the tedium by feigning a medical emergency (though my colleagues would probably assume I was bored and messing around, then ignore me anyway).

So, I was taken aback during a routine meeting with close colleagues in early 2018 when I found myself fighting back tears. I wasn’t speaking and the point under discussion did not relate to me. I could feel my throat constricting and the effort to prevent the tears from flowing had me clenching my jaw, tensing my leg muscles under the table, and wiping my specs as a distraction.

Within a few minutes, the sensation passed. A silent what-the-hell-just-happened relief washed over me and I mentally rejoined the meeting. For the rest of the day, my unspoken mantra was: You’re fine, you’re fine. Shake it off.

There it is: denial. I told myself nothing happened despite the evidence to the contrary.

Trauma

Over many years I’d grown increasingly aware of the psychological and emotional impacts of traumatic experiences that people go through or witness. I’d seen different friends and colleagues affected by their involvement in major disasters: the Bradford City stadium fire; the Zeebrugge ferry disaster; searching for body parts at Lockerbie.

I’d seen human trauma – and secondary trauma – for myself in Zambia in 1990–92 when HIV/AIDS devastated people and communities around me. A decade later, as a chaplain in the RAF, I spent the first five months of the 2003 Iraq War in the military hospital at RAF Akrotiri in Cyprus. Long days spent with wounded, maimed, injured and dying soldiers, airmen, sailors and the occasional civilian airlifted from battlefields in Iraq and Afghanistan. Watching exhausted surgeons, doctors and nurses doing the real work. ‘Kinforming’ (next-of-kin casualty notification) is possibly the hardest thing I’ve ever done.

My unspoken mantra was: You’re fine, you’re fine. Shake it off.

In one year in the Falkland Islands, I conducted 24 public or private memorial services. The latter were mainly for veterans of the 1982 Conflict who had returned to the islands to come to terms with their own psychological traumas, to lay ghosts to rest. We offered words of remembrance, silence, and tears, from the Military Cemetery at San Carlos to Mount Longdon, Fitzroy, and many others.

Some scars – and burns – were visible but mainly they were not. In 2004 and 2005 veterans of that conflict were presenting themselves to doctors and psychologists and military charities for the first time. Working on those timelines, there are still plenty of people who were part of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and others involved in non-military traumas, to accept they’ve been affected and to seek help.

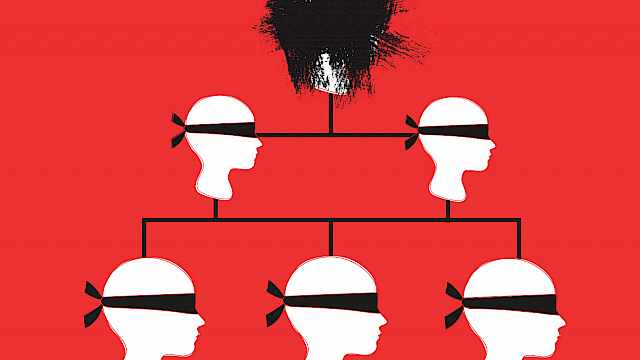

Denial

Over time, a pattern emerged in my attitude towards psychological harm: it was real but it was also something that happened to other people. If I was witnessing or supporting someone else’s trauma then it obviously wasn’t my trauma. It didn’t affect me. It couldn’t affect me if someone else lost a limb or a face or a life. Could it? Even if I can still recall the smell every day?

I avoided thinking about my own experiences. After all, they were tame compared to all those people who had really suffered. Definitely not worth making a fuss about.

More denial.

For years I told myself that everything I’d seen and done made me more resilient. Further denial. Maybe in some ways, it did. However, when my fighting-back-the-tears-in-a-meeting moment happened again the next day, it was time to admit that maybe I was not as resilient as I thought. That maybe I should speak to someone.

So, probably some 15 years too late, I mentioned to my wife and my line manager that I wasn’t okay. The sky did not fall on my head. What happened next is a story for another day, but I finally sought help to come to terms with how I’d been affected.

Pause

Like the permanent muscle weakness after a sports injury, I know that I will be mentally susceptible in some extreme situations or subjects. I don’t try to avoid them but sometimes I warn colleagues or a lecture audience if I find a topic highly sensitive. Life goes on.

If you are ever aware that what you are saying and presenting to the world is absolutely not what you are feeling or experiencing on the inside, pause for a minute. Especially if you have experiences in your past that others might describe as traumatic. You wouldn’t describe them that way, obviously, because you don’t get affected like other people do. But just in case, you might consider talking to someone about it. Ideally, before 15–20 years have passed.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)