The April 3 bombing on the St Petersburg metro was the highest-profile terror attack on Russian soil since a suicide bombing at Moscow’s Domodedovo airport in January 2011. According to Russia’s National Antiterrorism Committee, at least 14 people were killed and 49 injured by an improvised explosive device; further casualties were prevented when a second device was disarmed at another station. Days later, another bomb was found and defused in a residential building. ![]()

The prime suspect is reportedly Kyrgyzstan-born Russian citizen Akbarzhon Jalilov, who was identified on CCTV and died in the attack.

The use of explosives and the success of the attack despite heightened security measures – President Putin was in St Petersburg at the time, and national newspapers Izvestiya and Kommersant both reported that the security services had advanced warning that an attack was planned – makes it unlikely he acted alone. Indeed, Russian authorities have detained three people suspected of being involved in the bombing.

Still unclear, then, is whether the attackers had the help of an organised group – and there are many organisations that could be considered plausible instigators.

An obvious candidate is the so-called Islamic State (IS), which has drawn plenty of recruits from across the country. Some of them have remained in Russia, and the group is now set on inspiring attacks globally as its strongholds in Iraq and Syria come under pressure. It has also claimed multiple attacks in Russia to date, as well as targeting Russian interests abroad – most notably downing a Russian passenger jet over Egypt in October 2015.

But IS is far from the only terrorist group that attracts Russian-speaking recruits. North Caucasians and Central Asian radicals have joined a range of al-Qaeda-affiliated and independent radical Islamist groups fighting in Syria and Iraq, many of whom are hostile to Russia.

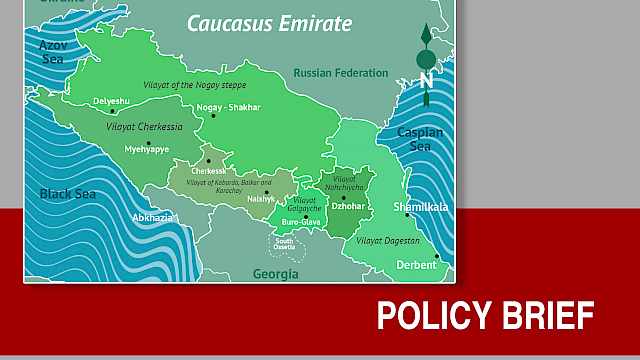

Furthermore, although it has been under heavy pressure from the Russian state in recent years, the North Caucasus continues to deal with low-level insurgent violence. The most senior surviving insurgent leader, Chechnya’s Aslan Byutukayev, is a former head of the reconstituted Riyadus Salikhin group that, as part of the Caucasus Emirate, was responsible for multiple suicide attacks, including that on Domodedovo airport.

Pressure on the domestic insurgency has driven a number of key rebel commanders out of the region. Many have relocated to Turkey; after the metro attack, news agency Rosbalt claimed investigators were pursuing their involvement as one of two main theories, citing increased activity among these leaders. The other main grouping under suspicion, it said, is far-right nationalism: groups in St Petersburg are known to have close links with their Ukrainian counterparts, and have used explosives in previous attacks.

To make things more complicated, not all of these groups are mutually exclusive. Most of the rebels still active in the North Caucasus are aligned with IS, while multiple groups have links running through Turkey. That there are so many potential culprits at work gives some indication of the scale of the threat Russia faces.

Sophisticated attackers

Another particularly telling aspect of the St Petersburg attack is its relative sophistication. Since the inception of IS, groups led by or affiliated to it have used a range of methods, including sophisticated car and truck bomb attacks. Turkey has lately been hit by several co-ordinated incidents that caused considerable casualties, including the Ataturk airport attack in June 2016 and the Istanbul nightclub attack on New Year’s Day 2017.

Elsewhere, IS has targeted airliners and used co-ordinated suicide attacks and marauding shooter attacks, as well as mass hostage-taking with suicidal intent, as happened in the 2015 Paris attacks. But the group has also claimed responsibility for unsophisticated attacks using mundane weapons such as knives, as well as lorries and cars. These are low-cost, easily accessible tools that can cause havoc easily, and IS is apparently relying on them more and more – presumably in a bid to outmanoeuvre counter-terrorism strategies.

IS has claimed responsibility for several attacks on Russian soil, which have mostly been at the unsophisticated end of the spectrum. An August 2016 incident near Moscow and a December 2016 attack in Grozny both saw policemen attacked with hand-held weapons. A 4 April attack on police in Astrakhan, claimed by IS two days later, appears to have followed a similar pattern. A number of the IS-linked attacks occurred in the restive North Caucasus republic of Dagestan, a focal point of regional violence where it’s hard to distinguish between targeted terrorist acts and day-to-day instability.

The St Petersburg attack, on the other hand, was more sophisticated: The perpetrator was clearly able to build at least one viable explosive device – even if the second failed to detonate – and possibly received training in making them. He was also able to do what he did despite the fact that the authorities apparently had intelligence of some sort about this specific attack, and despite widespread awareness that a terrorist incident of some sort was likely – as with London, a question of when rather than if.

All this goes to show that Russia faces some very serious domestic terrorism threats. The group or groups behind them are clearly able to inspire, enable and/or support attackers from afar; the question is whether they can provide the training and equipment required for mass-casualty attacks.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.