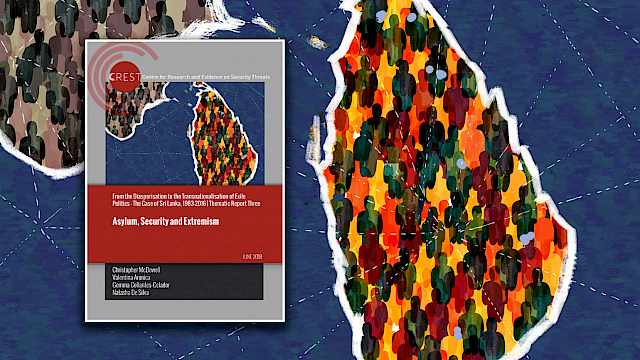

The defeat of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in brutal final battles in May 2009 reverberated around the world. An estimated one million Sri Lankan Tamils left the island over the three decades following the outbreak of civil conflict in 1983 settling in Europe, North America, Southeast Asia, and Australia.

The immediate reaction to the manner of the defeat, the violence against civilians and attacks on hospitals, among these communities was one of anger. Major cities such as London, Ottawa, and Sydney saw large demonstrations, hunger strikes, and the lobbying of governments to intervene in Sri Lanka to stop what placards described as “genocide” against the Tamil people.

Almost eight years on from the final battles in north-eastern Sri Lanka, the anger has not subsided. However, and contrary to what many predicted at the time, the response of diasporic Tamils has not been resurgent support for the LTTE and armed struggle for a separate Tamil state. Rather, the response has been a commitment to international and national legal processes to chart the future of the island.

In our research, we seek to understand why the political orientation of overseas Tamil communities embraced non-violence and placed its faith in transitional justice. The answers can be found in Sri Lanka as well as in the countries of settlement.

We seek to understand why the political orientation of overseas Tamil communities embraced non-violence and placed its faith in transitional justice

The defeat of the LTTE was total. The military, political and civil structures established since the mid-1980s collapsed. Tamils in the diaspora had been prepared (or felt that they had no choice) to show support for the LTTE during the Civil War. With its defeat, the LTTE was shorn of its status as the only group able to protect Tamil civilians. It lost the very basis of its appeal to Tamils abroad who were worried about friends and family at home, or of those who still believed that a separate state was achievable and violence might be necessary to accomplish it.

The LTTE ‘Boys’ previously active in Europe and North America, managing the information war and propagating the mystique of The Tigers, found that their previously pliant audience had evaporated.

For the first time, there was an open discussion about the corruption of the organisation, having collected millions of dollars in ‘voluntary donations’ and through criminal activities, and questions were asked about the division of the spoils by former leaders with knowledge of the bank accounts.

Even before the defeat, support for the LTTE and the separatist cause were waning among overseas Tamils.

Over the 30 years of asylum, migration, and settlement, Tamil communities had become more diverse and more representative of the population in Sri Lanka in terms of class, caste, and geographic origin. Social and cultural institutions were gradually re-established, marriages forged together strong families, and success in education and business created wealth and a vision for the future.

As overseas Tamils put behind the asylum and refugee labels and embraced citizenship, there was an increasing sense of confidence in what it meant to be a Tamil abroad.

The nationalism of the LTTE, rooted in a centuries-old dispute about the first settlers on the island, and an ideology reliant on a narrow and antagonistic construction of ethnicity and identity, chimed less and less with the values of internationalism and cosmopolitanism now familiar to second-generation Tamils. Their new social identity gave them the confidence to challenge the politics of the past.

Tamils' new social identity gave them the confidence to challenge the politics of the past

As with all established communities, Tamils in the West who trace their heritage to Sri Lanka have elites from the business, professional, and political world. These campaign for justice, to hold those in power to account for past human rights abuses and war crimes, and advocate for a constitutional solution to the island’s problems.

Western governments and international institutions engage with elites when pressured to do so. The government in Colombo, and indeed the political representatives of Tamils in Sri Lanka, remain cautious of the diaspora, wanting their investment but fearing them unreliable as allies.

Faith in a constitutional, justice-based and internationally mediated way forward for Sri Lanka remains strong among overseas Tamils. However, the risk remains that if the reform, truth and justice mechanisms do not deliver and reconciliation fails, then frustration among the diaspora will grow and positions will likely harden.

The Sri Lankan case raises interesting broader questions about the factors that shape attitudes towards a political cause at home held by those who have created a new life elsewhere. This might include the preparedness to defend or oppose the use of violence.

The organisational and resource capacity of a group to maintain an international network of supporters with direct links to overseas communities, and the ability to control the political narrative through the management of propaganda is critical. Important also are issues around identity and levels of integration in host countries, which affect the ways in which diaspora communities receive a rationale for violence, and view options for political settlements back home.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.