The risk assessment and management of at-risk individuals is widely used in terrorism prevention. While this relies on the judgment of practitioners, little is known about their perspective on risk assessment, and what they think is vital to the role.

We conducted a pilot study to explore this important gap in the knowledge. For this, we asked 41 professional threat and risk assessors a range of questions across three topics:

- How, where, and by whom should terrorism risk assessments be conducted?

- What training and experience should assessors have?

- Which abilities and characteristics make a ‘good’ assessor?

The assessors surveyed came from a variety of countries and backgrounds, including law enforcement, mental health/forensic psychology, and intelligence/security. Their experience spanned from less than one year to over ten years; 44% had over ten years of experience. Sixteen assessors had direct experience using terrorism risk assessment tools, while 21 had seen or heard of them.

While the small sample size and mix of experience limit the inferences that can be made, the results nevertheless suggest some interesting and useful implications. Here is a summary of what we found, and what it means for practice.

Conducting terrorism risk assessments: what, how, where, and who?

Which tools?

First, we asked the 37 assessors who had experience or knowledge of terrorism risk assessment tools about the tools they recognised, and their strengths. The most widely recognised tools were the commercially available TRAP-18 and VERA, followed by HMPPS’ ERG22+. Assessors valued the ease of use and availability of the tools, as well as the usefulness of the risk and protective factors they contained.

Where?

Risk assessments can take place in person with the subject or service user, remotely (using case files and other information), or using a combination. Most assessors in the sample recommended that these assessments should be conducted in person, however, of the 16 who had direct experience in conducting terrorism risk assessments, most did so remotely. This mismatch between recommendations and practice indicates that ‘best practice’ may not always be possible, depending on the context.

Who?

Assessors come from a range of disciplines; panels are often multidisciplinary. Our sample recommended that risk assessments can be conducted by specialist threat or risk assessors, mental health professionals, law enforcement officers, or intelligence analysts. Most did not support the use of algorithms to replace human decision-making.

Assessors suggested that between one and ten assessors should evaluate each case. Although there was disagreement as to the exact number, most assessors favoured a panel of two or three.

Assessor training and experience

Formal education

The assessors in our sample recommended that terrorism risk assessors should have at least tertiary (university level) education. However, professional training and experience were considered more important.

Professional training and experience

A range of different training and professional backgrounds were suggested, with no clear consensus. Recommendations included training in specific tools or Structured Professional Judgment (SPJ) protocols, in general principles of threat and risk assessment, and in psychology or mental health. Most assessors also agreed that previous professional experience is desirable, highlighting previous psychology/clinical, law enforcement, and risk assessment experience.

Some assessors also highlighted that specific knowledge of the terrorism field was desirable, as well as practical skills and experience such as supervision, interview techniques, and working with people.

It is likely that this range of training and experience reflects the diverse needs across the different disciplines and contexts involved in terrorism risk assessment (e.g. in the pre- or post-crime space). These findings also highlight the value of a multidisciplinary approach with mixed panels, which can bring a range of experience and knowledge to the process. Overarching training in specific tools and general risk assessment principles can help to bring these disciplines together.

Abilities and characteristics

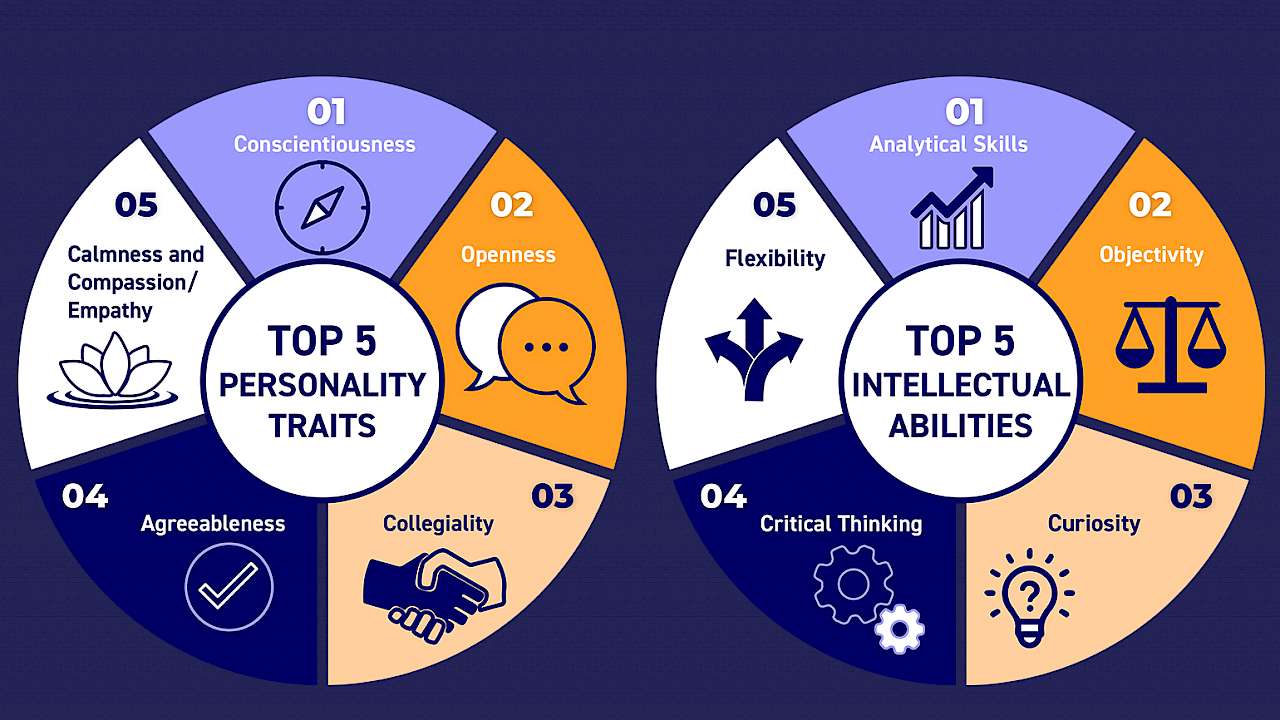

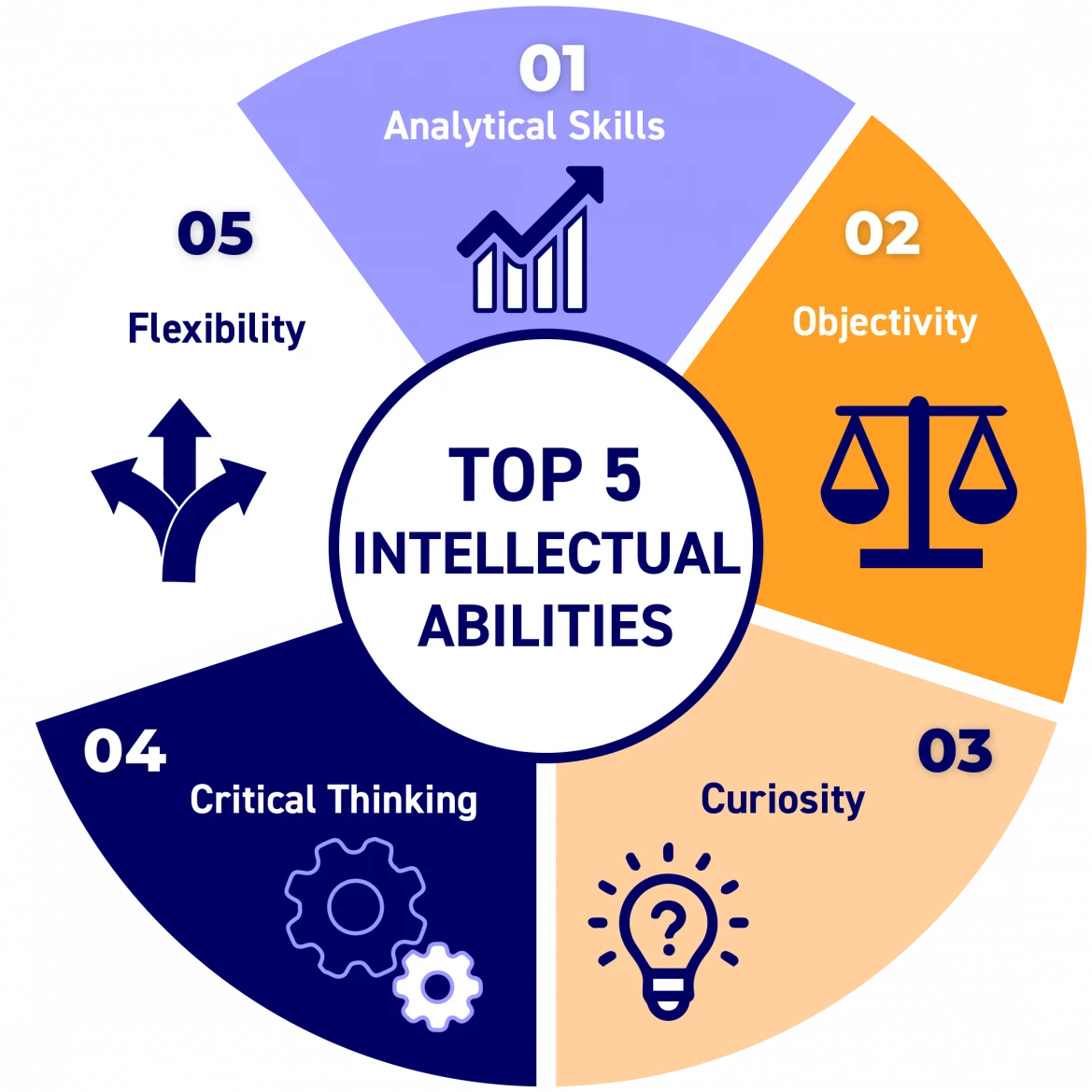

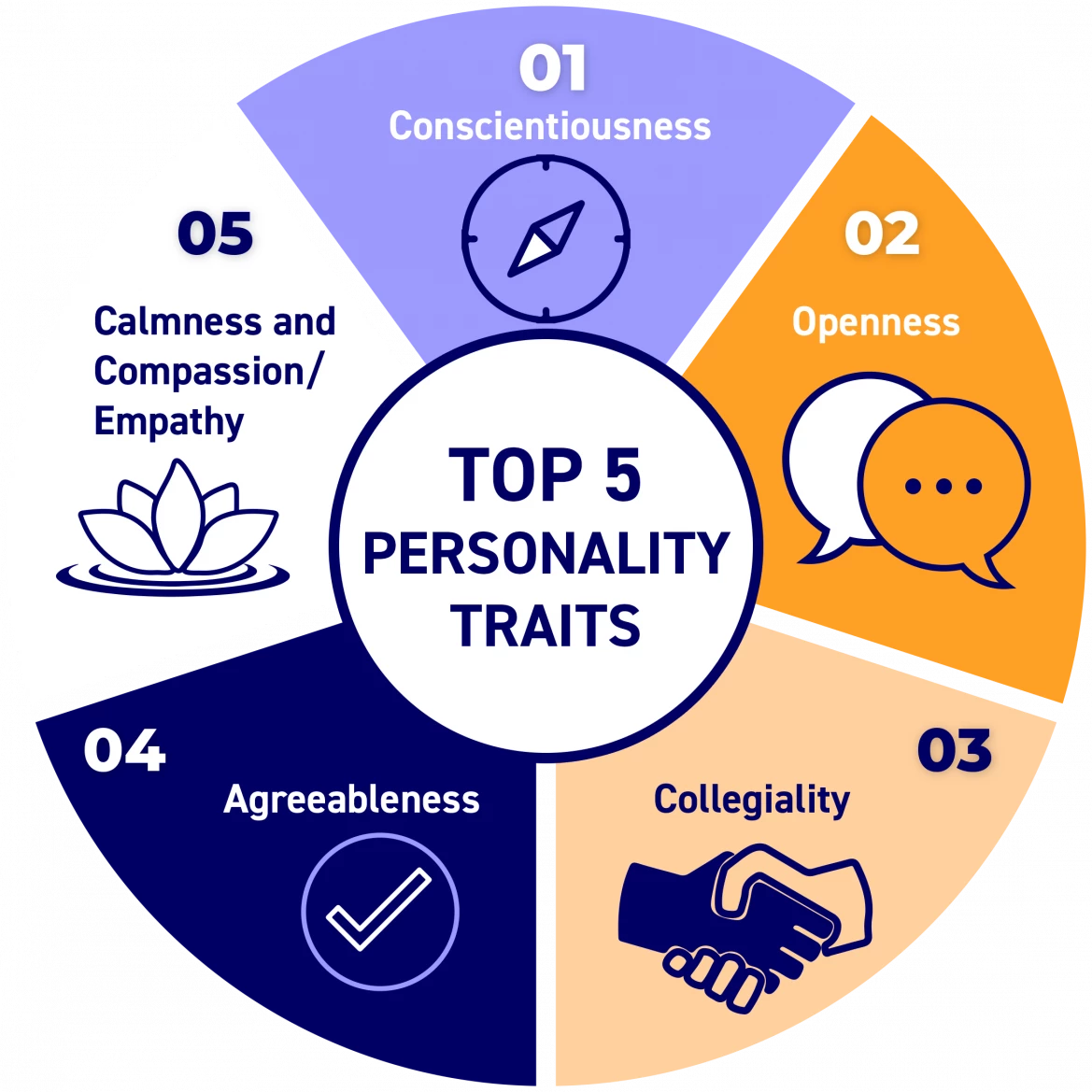

Finally, we asked assessors which intellectual abilities and personality characteristics they would expect of a ‘good’ risk assessor.

It could be said that possessing and developing these abilities and characteristics may be helpful to the risk assessment process. For example, findings from previous research suggest that more conscientious assessors may be more accurate and reliable in their judgments (Hanson et al., 2007). It is also possible that more personable assessors (i.e. collegial, agreeable, and compassionate) may build a better rapport with colleagues and service users. However, research is needed to evaluate the impact of these characteristics in practice.

Putting it into practice

Our study findings indicate that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to terrorism risk assessment; the process and requirements for assessors will likely be guided by the context in which it takes place and the agencies involved. However, based on the opinions of practitioners, some general suggestions and considerations can be made for future practice and evaluation:

- Risk assessment tools and SPJ protocols, and their training, should be designed with practitioners in mind, particularly considering their ease of use and availability.

- Consideration should be given to the advantages, disadvantages, and practicability of in person or remote assessment. Consideration should also be given to the number of practitioners assessing each case – at least two may be optimal.

- Professional training is more important than formal education. This could include training in the use of specific tools or protocols, as well as general principles of threat and risk assessment. Other training will depend on the context and discipline of the assessor, where multidisciplinary teams can bring a range of experience and skills to the assessment process.

- Some intellectual abilities and personality characteristics may be helpful to the risk assessment process. More objective and conscientious assessors may be more accurate and reliable, while more personable approaches may improve rapport-building with colleagues and service users.

Read more

- Hanson, R. K., et al. (2007). Assessing the risk of sexual offenders on community supervision: The Dynamic Supervision Project. Ottawa, Ontario: Public Safety Canada. Available at: tinyurl.com/s8m5h4j5

- Salman, N. L., & Gill, P. (2020). A survey of risk and threat assessors: Processes, skills, and characteristics in terrorism risk assessment. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 7(1-2), 122–129.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)