By 2013 over 11,000 children were reported killed in the Syrian crisis. Equally disturbing has been the other side of such victimisation. Children are just as likely to be targeted for mobilisation into militant activity.

The phenomenon of ‘child soldiers’ is far from new, but it’s an issue rarely considered in the context of terrorist conflict. However, in Syria and Iraq all armed groups, even groups supported by western governments, employ children in some capacity.

The scale of child mobilisation into such groups is difficult to gauge. Nobody really knows how many children have been trained by the Islamic State. A conservative estimate would be that somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000 children graduated from Islamic State (IS) training between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2016. That’s more than two children a day.

The experience of IS child soldiers

Children come to the Islamic State through at least five distinct pathways:

- Accompanying parents, guardians, or older siblings who travel to the Islamic State

- Via local parents who willingly allow their children to become involved

- Via local parents from whom the children are forcibly removed

- Via local orphanages in areas where IS has assumed de-facto social control

- Children who run away either alone, or with close friends, from local areas or even from abroad.

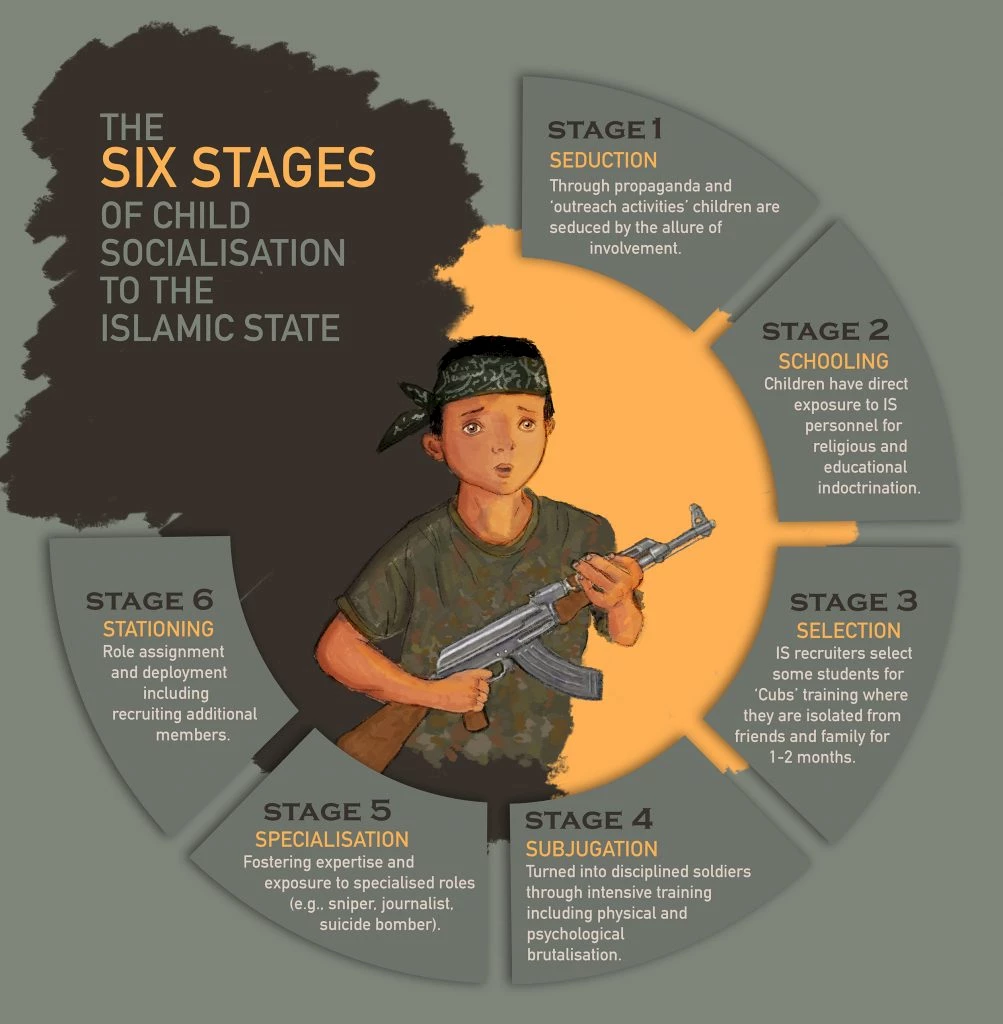

The result is what appears to be an institutionalised approach to socialising children into IS. The process turns them from passive bystanders into fully-fledged militants in six stages.

Initially, children are seduced by the allure of involvement. They consume propaganda or witness IS’s ‘outreach activities’, where the movement’s goal is to project a positive, service-providing and popular face.

Through schooling (under IS control) children have direct exposure to IS personnel for religious and educational indoctrination. This also marks an opportunity for selection, where IS recruiters choose some students for ‘Cubs’ training – 30 to 60-day training camps where they are isolated from friends and family.

A key quality of the child’s experiences here is subjugation. They are brutalised, disciplined, and turned into soldiers. Graduates will encounter specialisation in a particular role (e.g. sniper, journalist, suicide bomber) before stationing for duty.

We analysed thousands of propaganda items issued by the Islamic State and second-hand accounts of adult and child former members. Given the limited nature of that data, any attempts to understand this process must be seen as exploratory. What we have learnt, though, is that IS turns children into militants through a process of informal social learning.

This confirms previous research on this process by the anthropologist Karsten Hundeide. Hundeide found, as in our IS data, that children are made to feel welcome, then adopt style and identity markers (e.g. language, uniform) of their new ‘in-group’.

The child then slowly learns to redefine the past, in order to readily accept a set of new values. This helps the child ‘understand’ who the enemy is. Sacrifice and hardship (in this case through military training) are coupled with daily tests of loyalty and discipline.

A final test of loyalty (e.g. raping, or executing a prisoner) affords the child the new status as a fully committed insider.

This is gradual, systematic, and more linear in nature than most accounts of adult involvement.

The challenge of rehabilitation

The territorial decline of the Islamic State means there is an urgent need to develop solutions to the problems faced by these children.

Based on our understanding of child soldiers in other conflicts, we can make some basic assumptions. Most importantly, we need to understand child socialisation into the Islamic State as a type of victimisation.

Our six-stage model captures how IS has mastered and institutionalised child abuse. However, although accounts of children’s experiences with the Islamic State naturally leads us to characterise them as passive victims, the reality is more complex and equally unsettling.

From a psychological perspective, we will need to address the effects of indoctrination and of trauma.

In previous research on former child militants in Sri Lanka’s Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), children were found to have been explicitly taught how to ‘hate the enemy’. In the case of IS, young people have been subjected to a level of de-individuation and ‘identity reshaping’ so profound that it exceeds in focus and intensity what most adult recruits to IS experience.

Some IS children may be more overtly ‘ideological’ than others, in the sense of being able to articulate or parrot ideological content. Ideology remains very poorly understood in children and adults alike.

Studies of adult terrorists typically view ideology in one of two ways: as a precursor to involvement in violent extremism (e.g. a stepping stone) or as a by-product of involvement (i.e. whereby a person becomes more ideological after being recruited).

After listening to accounts of child recruitment, it might seem logical to assume that children are more ‘vulnerable’ to ideological commitment. But though a child may parrot ideological content, that doesn’t necessarily mean that they understand it. And in any event, that may not necessarily be the most important point; the more significant qualities of childhood trajectories into violent extremism are probably their social and psychological aspects.

IS children have lost people close to them, seen dead and wounded bodies, killed or violently assaulted others, and faced death themselves

Trauma will also be a key issue. IS children will have lost people close to them, seen dead and wounded bodies, killed or violently assaulted others, and faced death themselves. Such experiences have a profound and long-lasting psychological impact.

Studies of former LTTE child militants show they exhibited an array of psychiatric conditions including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and severe psychosis; in sum, the children were psychological wrecks. Sadly, the same will be true of many of those leaving IS.

Conflict-related symptoms persist in the longer term where insufficient attention is paid to issues experienced after the conflict. We need to pay attention to these and not just war-related trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. Issues such as personal loss during the conflict, family abuse, or neglect and the stigma of association with the conflict all lead to the internalisation of negative psychological symptoms over time.

Each case will, however, need to be assessed individually. Children who return from the Islamic State will have had different experiences and will present different challenges. Some will be traumatised, others will not. For children involved in militancy, their accounts will vary considerably.

Former IS Cubs will need practical as well as psychological support. Access to quality education, vocational and life skills training (to help prepare for civilian life and jobs) are essential, as is access to and use of interim care centres to assist with the reintegration process.

To mitigate recidivism, we will need a way of determining whether, how, and when children are prepared to re-enter civil society. The failure to properly address this results in many demobilised child soldiers becoming even more disturbed.

A further problem surrounds ‘stateless’ children, born of foreign fighters and most likely of rape. As highlighted by Human Rights Watch, these children do not have identification papers or birth certificates and as such are not able to prove their nationality. As well as discrimination and lack of access to resources, history also shows us that these children are more vulnerable to prostitution, trafficking, and recidivism.

What can we learn from other attempts to deal with former child soldiers?

Although we can draw on previous experiences of dealing with child soldiers, few ‘best practices’ have been identified from evaluations of such programs that can readily be harnessed for dealing with child returnees from IS. However, insights from research in Sri Lanka, Colombia, and Pakistan can inform our approach to children who have been involved in terrorism.

One child-centred program in Pakistan’s Swat Valley successfully reintegrated 156 youth back into their communities between 2010 and 2014

One child-centred program in Pakistan’s Swat Valley successfully reintegrated 156 youth back into their communities between 2010 and 2014. This project provides its students with all the facilities needed for their education, food, clothing, entertainment, and accommodation. A similar programme in Colombia, where more than half of FARC’s militants were recruited as children, also reports positive outcomes.

However, other research highlights contrary views, including from some children who felt forced to deny their past and to accept an identity that they didn’t recognise to be theirs.

Most programs involve the conflict ending and children being reunited with their families, an outcome which is strongly recommended in general, but which will not be viable in cases where the families were complicit with the children’s socialisation into IS in the first place.

However we go forward, the success of rehabilitation programmes will depend on continued monitoring and advocacy, practical assistance for demobilisation and rehabilitation, effective use of political and military leverage by international actors, and an uncompromising commitment by local, national, and international authorities to hold perpetrators accountable.

The scale of the challenge facing children affected or displaced by IS is staggering. The danger of recidivism is high if programmes fall short in rehabilitating children. Three-month programmes that merely focus on disarmament are too short to guarantee any type of sustainable rehabilitation; much longer programmes will be needed if children who have been in Islamic State are to be successfully rehabilitated.

Sadly, it’s clear we have a long way to go in understanding how to create an effective rehabilitation program for the thousands of children mobilised by Islamic State.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)