The United Kingdom (UK) is made up of three distinct legal jurisdictions (i.e., England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland) with differences in the types of data collected and counting practices with respect to the charging, prosecution and sentencing outcomes (prosecution landscape) of extremist actors. Having said this, the data that is publicly available is merely summary statistics and there is also no separate data available for Scotland. This has subsequently limited the capacity of researchers to analyse overall trends and compare jurisdictional data. Thus, the current study sought to provide a better understanding of the prosecution landscape for extremist actors in the UK by describing, analysing, and comparing the sentencing outcomes of individuals convicted of terrorism, terrorism-related and violent extremism offencesover a 21-year time period (April 2001 March 2022). To this end, we reviewed the relevant literature, undertook interviews with stakeholders, examined a sample of judges’ sentencing remarks, and created and analysed a sentencing database to answer a number of key research questions:

Offence Types

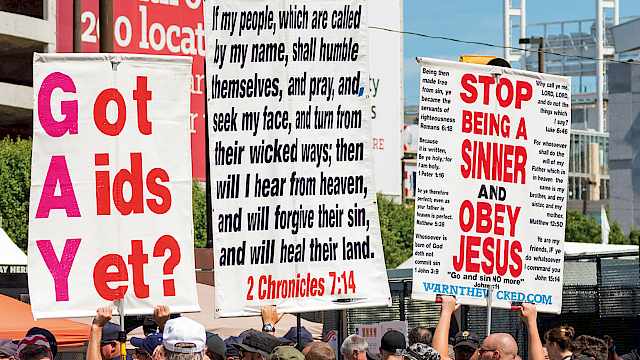

Terrorism offences are those offences under terrorism legislation but excluding those offences considered violent extremism. Terrorism-related offences are those offences under other legislation or the common law but which are considered terrorist-related. Violent extremism offences are those offences which "foment, justify or glorify terrorist violence in furtherance of particular beliefs; seek to provoke others to terrorist acts; foment other serious criminal activity or seek to provoke others to serious criminal acts; or foster hatred which might lead to inter-community violence in the UK" (Crown Prosecution Service, 2015).

1. What criminal offences are extremist actors being convicted of?

In our statistical model predicting offence type, Northern Ireland-related extremist actors are far more likely to be convicted of terrorism-related offences than terrorism or violent extremism offences. This is one of the clearest differences evident from the data. Despite being convicted of terrorism and violent extremism in approximately equal proportions, right-wing offenders are the most likely of all motivation groups to be convicted of violent extremism offences, and Islamist offenders are more likely to be convicted of terrorism offences. In England and Wales, the two most frequent principal offences that extremist actors were convicted of were terrorism offences, specifically preparation of acts of terrorism (23%) and collecting information likely to be of use to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism (14%). In Northern Ireland, the two most frequent principal offences were terrorism-related offences, namely attempting to cause an explosion, or making or keeping explosives with intent to endanger life or property (21%), and the offences of murder, manslaughter and attempted murder (14%). Due to a very small number of cases in Scotland, five principal offences all had the same frequency (14%). Three of these offences constituted terrorism offences.

2. What sentences are extremist actors receiving upon conviction?

In all jurisdictions, judges and magistrates consider a number of factors when deciding the appropriate sentence for an offender. These factors include the seriousness of the offence, the maximum and minimum penalties contained in the legislation, the range of available disposals (e.g., fines, community sentences or imprisonment), the offender’s circumstances, the impact upon the victim, the protection of the public and the existence of mitigating (e.g., age, lack of criminal record, or guilty plea) and aggravating (e.g., lack of remorse, recidivism, and the harm to the victim) factors. Judges and magistrates can also draw upon case law, guideline judgements issued by the Court of Appeal, and where applicable, relevant sentencing guidelines.

According to our regression model, an individual most likely to receive the longest sentence would be a male with co-defendants, who does not plead guilty, is accused of multiple counts, and is charged with a terrorism-related offence.

Using some of these factors, we found sentence length is influenced by offence type, plea, and total counts (all variables with legitimate impacts), but sentence length is also impacted by extraneous factors of gender and co-accused (i.e., whether an offender has co-defendants). According to our regression model, an individual most likely to receive the longest sentence would be a male with co-defendants, who does not plead guilty, is accused of multiple counts, and is charged with a terrorism-related offence. In terms of gender, we find that the sentence length for males is nearly two-thirds higher than for females, accounting for other variables. This is consistent with previous research in the US on female terrorist offenders (see Alexander & Turkington, 2018). We did not find evidence that age, jurisdiction, or ethnicity (white vs. non-white) impacted sentence, nor that particular motivation groups received longer sentences than other motivation groups. However, key findings do not account for severity of offences. See the full report for further investigation of severity.

3. Is there any evidence of changes in sentencing over time?

In terms of fluctuations due to changing contextual environments, we were interested in whether sentences increased or decreased in the aftermath of notable terrorism events such as the 7/7 bombings in 2005 and the murder of Jo Cox MP in 2016. However, analysis of sentencing over time revealed that sentence length has remained relatively steady over the years included in the dataset. While two peaks were identified in 2007-2008 and 2017-2018 with respect to the number of Islamist offenders being convicted there was no corresponding change in sentencing outcomes. Similarly, for right-wing offenders the number of individuals convicted peaks in 2018 but there was no corresponding change in sentencing outcomes. These results indicate that significant terrorism events may impact the number of similarly motivated cases sentenced in subsequent years, but do not appear to impact sentence length. This aligns with previous research in the US which found in the periods after the Oklahoma City bombing and 9/11 that the number of individuals indicted increased (see Damphousse & Shields, 2007).

These results indicate that significant terrorism events may impact the number of similarly motivated cases sentenced in subsequent years, but do not appear to impact sentence length.

Analysis of all cases in England and Wales reveals no overall difference in sentences after implementation of the 2018 guidelines for terrorism offences, but an overall comparison was limited. Analysis of three specific offences (with adequate samples sizes pre- and post-guidelines) demonstrated an impact of guidelines. The findings demonstrated significant increases, with sentences for preparation of acts of terrorism and dissemination of terrorist publications being ~50%-59% higher (respectively) in the post-guideline period, and collecting information likely to be of use to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism sentences 85% higher. This is in line with insights from our interviews and wider criminological literature, which suggests that the introduction of sentencing guidelines may have contributed to greater sentence severity (see Allen, 2016).

Limitations

While our findings provide important insight into the prosecution landscape of extremist actors in the UK, some important limitations must be noted. In examining the prosecution landscape, we do so only by examining those extremist actors who have been convicted and sentenced, and their information is publically available. We are aware that relying on publically available information as an approach has its own drawbacks (see Gill, 2020). Despite these limitations, we feel these were outweighed by the benefits of now being able to share our data with other researchers.

Read more

Alexander, A. and Turkington, R. (2018). Treatment of terrorists: How does gender affect justice? CTC Sentinel, 11(8), 24-29. https://ctc.westpoint.edu/treatment-terrorists-gender-affect-justice/

Allen, R. (2016). The Sentencing Council for England and Wales: Brake or Accelerator on the Use of Prison? Transform Justice. https://www.transformjustice.org.uk/publication/the-sentencing-council-for-england-and-wales-brake-or-accelerator-on-the-use-of-prison/

Allen, G., Burton, M., Pratt, A. (2022). Terrorism in Great Britain: the statistics. Commons Library Research Briefing. London: House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7613/

Amirault, J., Bouchard, M. (2017). Timing is everything: The role of contextual and terrorism-specific factors in the sentencing outcomes of terrorist offenders. European Journal of Criminology, 14(3), 269-289.

Blackbourn, J. (2021). Counterterrorism legislation and far-right terrorism in Australia and the United Kingdom. Common Law World Review, 50(1), 76-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473779521989332

Crown Prosecution Service (2015). Violent Extremism and Related Criminal Offences. https://web.archive.org/web/20071226031630/https://www.cps.gov.uk/publications/prosecution/violent_extremism.html

Damphousse, K.R., Shields, C. (2007). The morning after: Assessing the effect of major terrorism events on prosecution strategies and outcomes. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 23(2), 174-194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043986207301362

Gill, P. (2020). The data collection challenge: Experiences studying lone-actor terrorism. Washington, D.C.: RESOLVE Network. https://www.resolvenet.org/research/data-collection-challenge-experiences-studying-lone-actor-terrorism

Jupp, J. (2022). From Spiral to Stasis? United Kingdom counter-terrorism legislation and extreme right-wing terrorism. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2022.2122271

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)