The emergency services must operate as an efficient, interoperable team during crises. Effective joint working enables team members to combine their knowledge, skills and expertise in pursuit of collective goals; namely, saving lives. However, the nature of emergencies challenges teamwork.

Teams have to operate under conditions of extreme uncertainty while managing multiple competing task demands. Imagine that an explosion has occurred in a busy city centre. The Police face the urgent task of identifying and neutralising any threats, while the Fire Service tackles fire outbreaks and assesses the risk of structural collapses in buildings. Simultaneously, the Ambulance Service must work to administer medical treatment and transport patients to hospitals. However, these tasks do not unfold in a linear fashion, as the success of one team’s mission often depends on the performance of another. For instance, paramedics cannot administer treatment unless the Police have effectively neutralised further threats and the Fire Service has dealt with any fires.

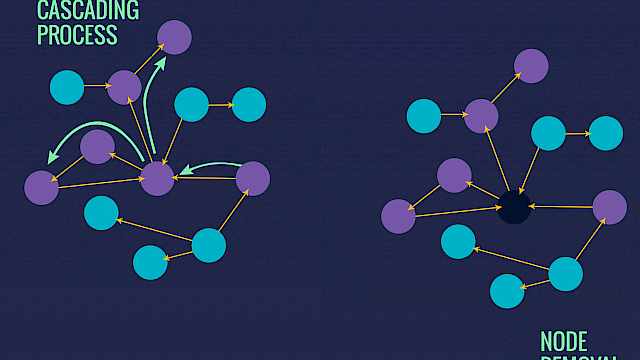

In this intricate web of interdependent tasks, a cohesive approach to interoperability is paramount to ensure the seamless coordination of activities in pursuit of the collective goal of saving lives.

The Psychology of Interoperability

Despite the importance of interoperability, its integration within the emergency services has proven challenging. JESIP (the joint emergency services interoperability programme) was launched in the UK in 2012 with the goal of improving interoperability, but the recent public inquiry into the Manchester Arena attack concluded that interoperability has not been embedded. We argue that this failure to fully integrate interoperability is due to a poor understanding of psychology. Teams are social units, which makes them inherently psychological. So if interoperability is to be seamlessly woven within the social fabric of the emergency services then a robust understanding of psychology is essential. Developing this understanding is the goal of our CREST-funded research.

Defining interoperability

A first step in our research was defining interoperability. Existing definitions were often vague and abstract, and so we sought to build a new definition of interoperability that identified its precise components. To do this, we conducted a systematic review of the literature and identified five components that are essential for interoperability to thrive.

We define interoperability as a shared system of technology and teamwork built upon trust, identification, goals, communication, and flexibility.

1. Communication

Interoperable teams must be able to prioritise efficient and meaningful communication, sharing relevant information while avoiding overload. This fosters a shared understanding and informed decision-making.

2. Flexibility

Successful interoperable teams must embrace flexibility and decentralisation. Team members should have a clear understanding of roles, which will enable adaptivity and effective action, even in the absence or overload of another team member. Flexible and decentralised teams allow responsibilities and decision-making authority to be distributed, aiding an efficient response.

3. Trust

Trust is a foundational element within an interoperable team. It encompasses different dimensions, including interpersonal trust (based on personal familiarity), role-based trust (having confidence in the competence and reliability of individuals to fulfil a specific role), and group-level trust (which extends to any member representing a particular organisation or profession). Establishing and maintaining trust within the team is vital for interoperability.

4. Identity

Emergency workers must maintain secure organisational identities within their interoperable team. Organisational identity refers to how individuals perceive themselves as members of their organisation and their sense of alignment with its mission and values. Efforts to promote interoperability, through changes in doctrine or training, should prioritise respecting team members’ identities to prevent identity threats and promote a positive, inclusive team environment.

5. Goals

Interoperable teams must have cohesive goals. While the overarching aim is saving lives, practical implementation may vary across roles and services. Translating and aligning goals enables harmonious teamwork and coordination, fostering a unified team.

Taken together, we define interoperability as a shared system of technology and teamwork built upon trust, identification, goals, communication, and flexibility. This definition can be used to empower researchers and end-users alike, pinpointing the vital components around which to design targeted interoperability research and training.

How do we train interoperability?

A second step in our research was to provide practical recommendations for how to train interoperability; identifying specific methods that can be used to, for example, build trust between team members. Through interviews with commanders from the Police, Fire and Ambulance Service, we found that regular face-to-face joint training is crucial for building knowledge, skills, breaking down barriers, fostering interpersonal and group-level trust, and promoting a shared sense of togetherness and collective teamwork. However, commanders acknowledged that resource and funding pressures make this type of training rare. Simulations were deemed a valuable compromise, offering time-efficient and resource-friendly opportunities for collaboration and exercising. Yet, even planned training sessions are frequently disrupted as Police and Paramedics are pulled away last minute to cope with operational demands.

So what’s next?

To enhance interoperability, it is essential to develop training programs that are explicitly tailored to foster social psychological connectiveness. The result of which will be stronger, more interconnected, efficient and robust emergency services. Yet, the realisation of this vision relies upon adequate investment in the Emergency Services; without such investment, this transformative goal will remain elusive.

Dr Nikki Power is a senior lecturer in organisational behaviour at the University of Liverpool. Dr Richard Philpot is a lecturer of Psychology at Lancaster University. Professor Mark Levine is a professor of Social Psychology at Lancaster University.

For more outputs (including an animation, guide, and poster) from this CREST-funded project visit crestresearch.ac.uk/interop

Read more

Power, N., Alcock, J., Levine, M., & Philpot, R. (2023) The Psychology of Interoperability: Study One Summary. CREST Guide. https://crestresearch.ac.uk/resources/the-psychology-of-interoperability-study-one/

Saunders, J. (2022) Manchester Arena Inquiry. Volume 2: Emergency Response. https://manchesterarenainquiry.org.uk/report-volume-two/

Copyright Information

© GWatkins | stock.adobe.com