The role of trauma as a precursor to violent extremism has received greater attention in recent years. That was not always the case, as theoretical and methodological obstacles within terrorism studies diverted attention away from identifying individual risk factors. The methodological obstacles included a lack of studies designed to collect nuanced, in-depth information related to trauma, such as life-history interviews. From a theoretical perspective, there existed long standing emphases on group dynamics which de-emphasised the importance of pre-existing characteristics that may increase a person’s susceptibility toward embracing extremism.

Outside of terrorism studies, scholars have long examined different risk factors across a broad range of fields. Arguably, most applicable for violent extremism, scholars have focused on the relationship between risk factors and the onset of antisocial behaviour. While no single risk factor ‘causes’ offending, research has identified various factors most likely to contribute to antisocial behaviour.

Towards a trauma-informed model of extremist participation

Informed by this tradition of research and an intensive life-history dataset, including interviews with more than 100 former US far-right extremists, our team studied how different adverse experiences influenced eventual involvement in violent extremism.

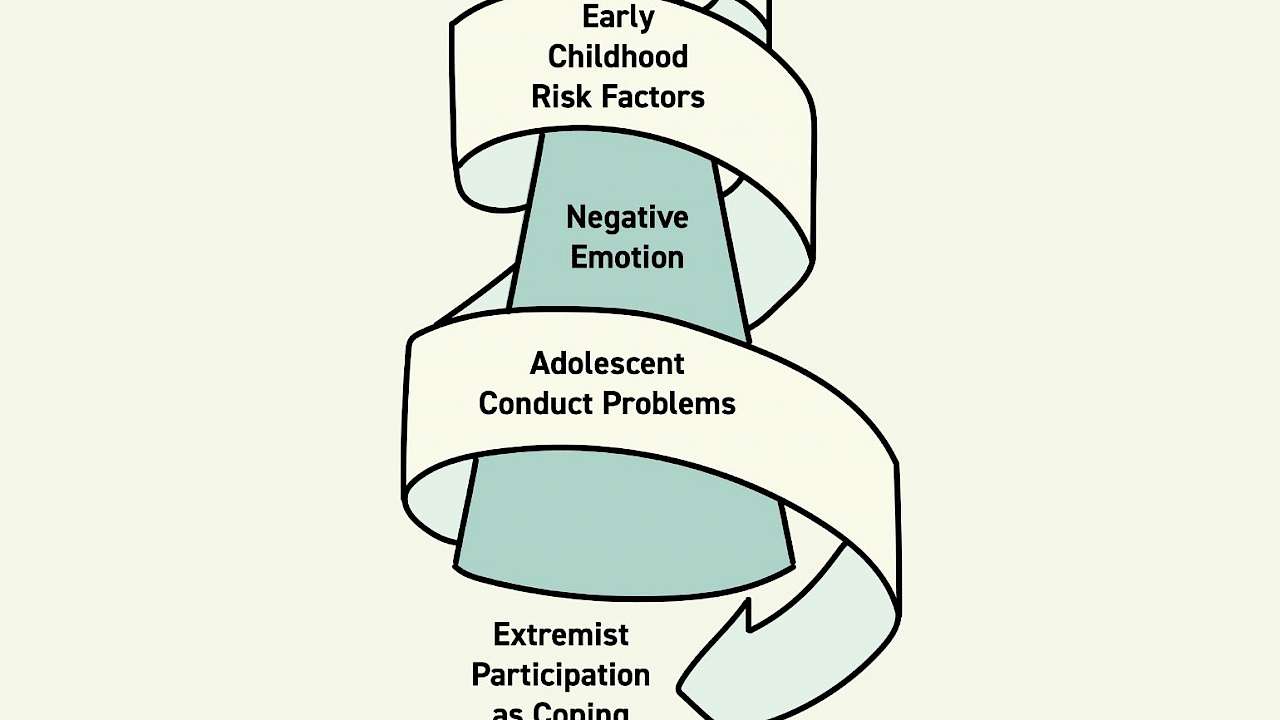

As part of our research, we developed a model for understanding how environmental adversities generate negative emotion states such as heightened levels of anger and depression, which, in turn, increase a person’s likelihood to engage in more generic types of maladjusted behaviour such as serious delinquency or self-harming behaviour. This combination of risk factors, negative emotions, and maladjusted behaviour creates a spiralling effect where the person experiences life course instability in terms of interrupted transitions, delayed maturation, and cumulative disadvantage.

My mom would leave me with her friend’s son. He did not rape me, but he was forcing me to give him oral sex… When my mom came home, I told her… I don’t think they ever talked about it. It was kind of like it did not happen. So, yeah, that was a turning point for me… I was definitely never a kid again after that like mentally because I wasn’t getting love from my family. I have always been really reserved since that.

– Alice, Interview 6, 10/30/2015

In turn, these individuals began experiencing ‘high risk’ lifestyles involving drug use, violence, incarceration, and homelessness. Over time, their vulnerabilities became more pronounced and routine activities increased their chances of exposure to violent extremism. Within this context of danger and instability, extremist groups became a support system capable of addressing basic physical and social needs.

The insecurities started from my dad not being a part of my life… you start to own that as a kid. You think it’s your fault and drugs became a coping mechanism. They were always my escape from reality because I didn’t want to look at myself, right? When the skinheads came up it became another escape.

– Kevin, Interview 51, 7/7/2014

We found that our participants were exposed to multiple forms of adversity. Specifically, 63% of the sample experienced four or more adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) during the first 18 years of their life.

Participants experienced a sense of rejection and status deprivation in response to these traumas. In turn, adversities heightened participants’ vulnerabilities to pulls associated with ideology and group dynamics. In short, the ideology and group context became vehicles to help them resolve their emotional distress and provide a status that was denied to them by their caregivers.

The ideology and group context became vehicles to help them resolve their emotional distress and provide a status that was denied to them by their caregivers.

Possible interventions

It is unnecessary to ‘reinvent the wheel’. Early interventions designed for at-risk youth and gang members could inform how we think about and apply countering violent extremism (CVE) and preventing violent extremism (PVE) initiatives. Interventions could be targeted at each stage of the model above to reduce the need for extremist participation as a coping mechanism.

To reduce early childhood risk factors such as ACEs, behavioural training programs could be generally offered as part of a ‘universal’ prevention strategy and/or targeted more specifically to at-risk groups. One such example is Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, which improves caregiver’s interaction and discipline skills, including decreased use of negative parenting behaviours (e.g., criticism, sarcasm, physical aggression), and increased use of positive parenting behaviours (e.g., attending to positive behaviours, labelled praise, reflections).

We found that negative family relationships typically preceded extremist onset. Promoting positive family attachments by counselling parents and youth may reduce these individuals’ drift toward extremist collectives and foster resilience to extremist recruitment efforts.

When abuse has occurred, we need to address the emotional consequences associated with abuse through therapy, counselling, and other types of social support. Prior research suggests that cognitive-behavioural approaches are successful for treating both preschool and school-aged children who have been sexually abused when the non-offending parent is included in the treatment process.

It is critical for relevant bystanders such as family members and school officials, to effectively respond to what may seem like relatively innocuous indicators of extremism. These indicators, such as a racist joke or a coded white supremacist slogan, may be symptoms of untreated trauma and the beginnings of adolescent conduct problems. They should be seen as opportunities to engage children rather than be ignored, minimised or just punished.

In summary, we advocate an approach to preventing violent extremism which draws on generic violence reduction interventions that have proven to be effective. This approach has efficacy, partly because our research found high levels of unresolved trauma common among other high-risk samples. This article highlights a few such interventions, and we encourage practitioners to explore the literature and engage widely with service providers from alternative violence reduction programmes.

Pete Simi is a Professor of Sociology at Chapman University. His research interests focus on cognitive and cultural sociology, social movements, political violence, and juvenile delinquency.

Steven Windisch is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at Temple University. As a collective, this research investigates the overlap between conventional criminal offending and political extremism. Dr Windisch is particularly interested in the transition from espousing extremist beliefs to committing extremist violence.

Read more

Hakman, M., Chaffin, M., Funderburk, B., & Silovsky, J. F. (2009). Change Trajectories for Parent-Child Interaction Sequences During Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for Child Physical Abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(7), 461-470. https://tinyurl.com/2e6k9ktv

Simi, P., Sporer, K., and Bubolz, B. F. (2016). Narratives of Childhood Adversities and Adolescent Misconduct as Precursors to Violent Extremism: A Life-Course Criminological Approach. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 53, 4: 536-63. https://tinyurl.com/yw7xa7t9

Steven, W., Simi, P., Blee, K., and DeMichele, M. (2020). Measuring the Extent and Nature of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) among Former White Supremacists. Terrorism and Political Violence. https://tinyurl.com/2p9cbbzs

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2022 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)