As discussed in a companion article (Moving away from ‘Trauma’ towards ‘Trauma and...’), trauma exposure and its possible mental health and psychosocial consequences has become a major focus in violent extremism and prevention programs and practices. Although many questions about trauma’s possible roles remain unanswered, and trauma is one of many interacting factors that can increase the risk of engagement in violent extremism, practitioners and policymakers acknowledge the importance of addressing trauma and its consequences as a critical part of preventing engagement in violent extremism.

These concerns have become even more pressing in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has been associated with increased adversity, stress, alcohol use, domestic violence, social isolation, mental health symptoms, and gun purchasing in many communities in the United States and globally.

Addressing trauma and its consequences is relevant for primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention approaches to violent extremism.

- Primary prevention involves population-level interventions to diminish risks and strengthen protective factors concerning involvement in violent extremism.

- Secondary prevention involves stopping those individuals at high risk from becoming involved in violent extremism.

- Tertiary prevention involves rehabilitating those who have already become involved.

This raises a key question: how can practitioners draw upon or modify existing trauma-informed approaches in the work of preventing violent extremism?

Trauma is one of many interacting factors that can increase the risk of engagement in violent extremism.

According to SAMSHA, a trauma-informed approach seeks to: “Realise the widespread impact of trauma and understand paths for recovery; Recognise the signs and symptoms of trauma in patients, families, and staff; Integrate knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices; and Actively avoid re-traumatisation.” The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) has done much to develop, disseminate, and train practitioners and service systems in trauma-informed approaches for children.

We recently held a workshop with leading trauma experts affiliated with the NCTSN to identify existing resources which could be deployed when working with individuals who are exiting violent extremist groups, including their children. We focused primarily on tertiary prevention for women and children returning from formerly ISIS-controlled territories, often referred to as R&R (for rehabilitation and reintegration). Based upon our research, we have expanded this framework to include 5Rs:

- Repatriation

- Resettlement

- Reintegration

- Rehabilitation

- Resilience

We identified several key trauma-focused approaches which correspond to each of the 5Rs.

Existing Trauma-Informed Models and the 5Rs Framework

Repatriation

The first R is repatriation which is enabling the return of persons to their country of origin or new country (in the case of children born outside).

Bringing them out of refugee camps where there have been military attacks will diminish their further exposure to trauma, deprivation, and extremist groups, and give them the opportunity to begin recovery.

Resettlement

The second R, resettlement, refers to meeting their immediate needs once repatriated.

In the first months of arrival, mothers and children may be experiencing emotional distress related to moving and prior trauma exposure. They can be helped by Psychological First Aid, especially when delivered by a local community member. Methods of stress reduction, such as grounding and deep breathing, can be especially helpful in managing emotional dysregulation. The goals are to maximise their coping strategies and connect them to existing supports.

Additionally, many mothers and children face situations where their husband/father is presumed dead (but nobody has been found) or where the father is in prison. These situations can be understood as different types of ambiguous losses based on the theory that some losses are not total but are partial, either psychologically or physically, and which can increase the likelihood of prolonged grief if left unaddressed.

To respond effectively, practitioners should familiarise themselves with ambiguous loss theory and assess and screen children and mothers for diverse types of loss experiences, including prolonged grief disorder. If present, prolonged grief can be addressed through Trauma and Grief Component Therapy, which would likely be addressed in subsequent 5R phases.

Reintegration

The third R refers to reintegration, defined as facilitating re-entry or entry into family, community, and society. This can be a stressful experience for mothers and children, which can be accompanied by anxiety, fear, worry, guilt, and memories. During reintegration, it is recommended to go beyond Psychological First Aid and apply the more expansive and intensive Skills for Psychological Recovery. This evidence-informed intervention can help adult and child survivors gain skills to manage distress and cope with post-disaster stress and adversity. It, for example, focuses on building problem-solving skills, managing reactions, and rebuilding healthy social connections.

Rehabilitation

The fourth R refers to rehabilitation, which is helping persons to grow and change so they can heal from the potential impacts of having experienced violence, displacement, violations of human rights and other trauma and continue to lead a life free of crime (given that most have not been involved in any criminal activities). Using psychotherapy to teach critical thinking skills and to promote cognitive flexibility can help reduce the tendency to fall back on rigid thinking regarding black and white approaches, grievances, or demonisation of particular groups of people or ways of living, which is often driven by fear, grief, humiliation, exclusion, discrimination, and insecurity associated with prior trauma exposure. Specific trauma models can be applied, including Cognitive Processing Therapy for women and Trauma Systems Therapy for children.

Resilience

The fifth R refers to resilience, which is the ability to navigate challenges and maintain a healthy, socially integrated, and crime-free life in the face of adversity. Resilience can consist of protective individual, family and community level attributes that enable individuals to achieve positive outcomes despite setbacks and stressors. In the context of R&R it is important to note that successful non-violent integration into society is a key outcome.

Resilience incorporates cultivating future orientation and a sense of self not narrowly defined by past trauma exposure. Resilient outcomes can be facilitated by leveraging and strengthening resources within an individual’s environment that are important for wellbeing. Thus, family-based models, including Multiple-Family Groups, can be used to strengthen key family relationships and family processes such as parenting or family beliefs and communication with the goal of improving overall family functioning.

Existing multiple family group interventions have been found to strengthen family relationships, enhance social support and decrease common mental disorders and behaviour problems in children and adults. This presents an opportunity to draw on this evidence base to strengthen families impacted by violent extremism. Resilience can also be built through Peer Service Models, which bring together individuals with similar life histories to deliver and receive support. The shared experience between peers is associated with reductions in stigma about mental health services, enhanced social support, and adherence to services.

For women and children impacted by violent extremism, this can involve implementing Peer Navigator Programs to assist women and children in accessing the care they need, training peers with shared life history to deliver evidence-based mental health services, and adapting existing peer support models to meet their needs, culture, and context.

Next Steps and Key Considerations

Some areas of trauma-informed practices will need modifications in order to address the manners in which trauma processes can interact with violence prevention. In the tertiary prevention space, we have found challenges involving the incarceration of husbands/fathers, which is a type of ambiguous loss.

Another common issue in the tertiary and secondary prevention spaces is multiple co-occurring traumas from different life periods (both before, during and after their violent extremist experience). Additionally, all intervention strategies should be tailored to the local socio-cultural context.

Aside from tertiary prevention, trauma-informed practices can apply in primary and secondary prevention. In the primary prevention realm, an all too common experience is persons who have been exposed to domestic violence, bullying, social exclusion, or discrimination themselves. Those who do not get the support or treatment they need are left on their own, searching for meaning, community, and purpose.

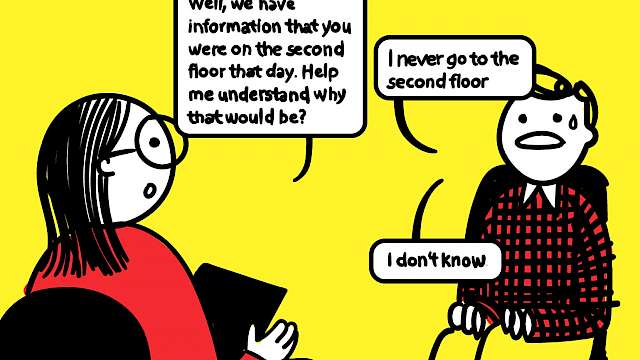

Recruiters of terrorist organisations or others purveying hate are skilled at identifying those vulnerable due to traumatic or adverse experiences and offering them a means of empowerment through joining the movement and taking violent action. In far too many cases, recruiters are the only ones who offer such support, not parents, teachers, or healthcare workers.

For those who have started to get involved with violent extremism but not yet committed a crime, trauma-informed approaches can be one component of wrap-around services utilised to offer an exit ramp.

There is a pressing need to find ways to facilitate access to trauma-informed approaches for those not likely to seek traditional mental health services. For those who have started to get involved with violent extremism but not yet committed a crime, trauma-informed approaches can be one component of wrap-around services utilised to offer an exit ramp.

Many mental health and other frontline health practitioners approach working in the space of violent extremism prevention with apprehension. One common fear is that they do not have the knowledge and skills to be helpful. Our hope is that more practitioners will realise they can draw upon their toolkit of trauma-informed practices to work in this new space of prevention of violent extremism. In this article, we have described several examples of trauma-informed practices, which build on the broader conceptualisation of trauma described in our other article.

We also believe the time has come for the topics of violent extremism prevention, violence prevention more generally, and the related field of risk assessment/management to be introduced into the training and continuing education curriculums for mental health professionals. This could help to build these skills among mental health professionals and increase the number of those who could engage in violence prevention activities, where they are desperately needed.

Stevan Weine, M.D., is Professor of Psychiatry at the UIC College of Medicine, where he also Director of Global Medicine and Director of the Center for Global Health.

Mary Bunn, PhD, LCSW is a Research Scientist in the Department of Psychiatry and Global Health at the University of Illinois Chicago.

Emma Cardeli, PhD, is a research associate and attending psychologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and an instructor of psychology at Harvard Medical School.

B. Heidi Ellis, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Psychology at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and the Director of the Trauma and Community Resilience Center.

Read more

Acri, M., Hooley, C.D., Richardson, N., & Moaba, L.B. (2017). Peer models in mental health for caregivers and families. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(2), 241-249. https://tinyurl.com/52n54hcz

Asmundson, G. J., Thorisdottir, A. S., Roden-Foreman, J. W., Baird, S. O., Witcraft, S. M., Stein, A. T., Smits, J., & Powers, M. B. (2019). A meta-analytic review of cognitive processing therapy for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(1), 1-14. https://tinyurl.com/ympamzn2

Bellamy, C., Schmutte, T., & Davidson, L. (2017). An update on the growing evidence base for peer support. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(3), 161-167. https://tinyurl.com/msxw4fd2

Berkowitz, S., Bryant, R., Brymer, M., Hamblen, J., Jacobs, A., Layne, C., Macy, R., Osofsky, H., Pynoos, R., Ruzek, J., Steinberg, A., Vernberg, E. & Watson, P. (2017). Skills for psychological recovery: Field operations guide. National Child Traumatic Stress Network. https://tinyurl.com/3zzpcymw

Boss, P., & Yeats, J. R. (2014). Ambiguous loss: A complicated type of grief when loved ones disappear. Bereavement Care, 33(2), 63-69. https://tinyurl.com/mrxkb5r2

Boss, P. (2006). Loss, trauma, and resilience: Therapeutic work with ambiguous loss. WW Norton & Company. https://tinyurl.com/3jbtyunj

Boss, P. (2004). Ambiguous loss research, theory, and practice: Reflections after 9/11. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 551-566. https://tinyurl.com/sk2zykpy

El-Khani, A., Cartwright, K., Ang, C., Henshaw, E., Tanveer, M., & Calam, R. (2018). Testing the feasibility of delivering and evaluating a child mental health recovery program enhanced with additional parenting sessions for families displaced by the Syrian conflict: A pilot study. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 24(2), 188. https://tinyurl.com/3mewzefh

Ellis, H., King, M., Cardelli, E., Christopher, E., Davis, S., Yohannes, S., Bunn, M., McCoy, J. & Weine, S. (under review). Supporting women and children returning from violent extremist contexts: Proposing a 5R framework to inform program and policy development.

Everly, G. S., McCabe, O. L., Semon, N. L., Thompson, C. B., & Links, J. M. (2014). The development of a model of psychological first aid for non–mental health trained public health personnel. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 20, S24-S29. https://tinyurl.com/2wsccxhm

Fisher, E.B., Coufal, M.M., Parada, H., Robinette, J.B., Tang, P.Y., Urlaub, D.M., Castillo, C Guzman-Corrale, L.M., Hino, S., Hunter, J., Katz, A.W., Symes, Y.R., Worley, H.P., Xu, C. (2014). Peer support in health care and prevention: cultural, organisational, and dissemination issues. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 363-383. https://tinyurl.com/ewtwhupu

Luther, S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The Construct of Resilience: A Critical Evaluation and Guidelines for Future Work child Development, Vol. 71, No. 3 pp 543-562. https://tinyurl.com/32ra9h95

McKay, M. M., Harrison, M. E., Gonzales, J., Kim, L., & Quintana, E. (2002). Multiple-family groups for urban children with conduct difficulties and their families. Psychiatric Services, 53(11), 1467-1468. https://tinyurl.com/243vvbrn

Ramchand, R., Ahluwalia, S.C., Xenakis, L., Apaydin, E., Raaen, L., & Grimm, G. (2017). A systematic review of peer-supported interventions for health promotion and disease prevention. Preventive Medicine, 101, 156-170. https://tinyurl.com/4znh3k5z

Resick, P. A., Monson, C. M., & Chard, K. M. (2016). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. Guilford Publications. https://tinyurl.com/vhmv8ux6

SAMSHA (2014). SAMSHA’S concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. https://tinyurl.com/mt6dnkkk

Saltzman, W., Layne, C., Pynoos, R., Olafson, E., Kaplow, J., & Boat, B. (2017). Trauma and grief component therapy for adolescents: A modular approach to treating traumatised and bereaved youth. Cambridge University Press. https://tinyurl.com/2c3veuc5

Saxe, G. N., Ellis, B. H., & Kaplow, J. B. (2007). Collaborative treatment of traumatised children and teens: the trauma systems therapy approach. Guilford Press. https://tinyurl.com/bdf2ayck

Solheim, C. A., & Ballard, J. (2016). Ambiguous loss due to separation in voluntary transnational families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(3), 341-359. https://tinyurl.com/5n8ysjen

Solomon, P. (2004). Peer support/peer provided services underlying processes, benefits, and critical ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27, 392-401. https://tinyurl.com/4k7jjpsd

Walsh, F. (2015). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). Guilford Press. https://tinyurl.com/3pr9vxuu

Wang, L., Norman, I., Xiao, T., Li, Y., & Leamy, M. (2021). Psychological first aid training: a scoping review of its application, outcomes and implementation. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(9), 4594. https://tinyurl.com/bdd58h6k

Weine, S. M., Stone, A., Saeed, A., Shanfield, S., Beahrs, J., Gutman, A., & Mihajlovic, A. (2017). Violent extremism, community-based violence prevention, and mental health professionals. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(1), 54-57. https://tinyurl.com/5ad7zpxe

Weine, S. M. (2011). Developing preventive mental health interventions for refugee families in resettlement. Family process, 50(3), 410-430. https://tinyurl.com/48cjfymz

Weine, S., Kulauzovic, Y., Klebic, A., Besic, S., Mujagic, A., Muzurovic, J., Spahovic, D.,

Sclove, S., Pavkovic, I., Feetham, S., & Rolland, J. (2008). Evaluating a multiple-family group access intervention for refugees with PTSD. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 34(2), 149–164. https://tinyurl.com/4vtxu7y2

Weine, S. M., Raina, D., Zhubi, M., Delesi, M., Huseni, D., Feetham, S., Kulauzovic, Y., Mermelstein, R., Campbell, R. T., Rolland, J., & Pavkovic, I. (2003). The TAFES multi-family group intervention for Kosovar refugees: A feasibility study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(2), 100–107. https://tinyurl.com/269zjwn9

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2022 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)