Trust is an important resource in managing our dependencies on others; it reduces our uncertainty, freeing up cognitive resources to allow more focus on the task in hand. Trust emphasises an individual’s willingness to be vulnerable, based on positive expectations of the intentions or behaviour of another to act at best in our interest, or at worst benignly. Such confidence stems from two dimensions: first, a rational cognitive-based trust derived from the trusted party’s past performance. It comprises insights into their skill and competence. It can extend to an organisational-level to include the systems and processes an organisation uses. The second dimension, affect-based trust, concerns the care, value and respect the other party shows us – a sense that they have our best interests at heart, so promoting greater levels of commitment.

In contrast, distrust involves pervasive negative expectations of the motives, intentions or actions of others. Trust, therefore, is to a large extent derived from the past, a bit like driving by looking in a rearview mirror, which is fine as long as the road remains the same. But what happens when an organisation faces things for the first time, such as having to make redundancies?

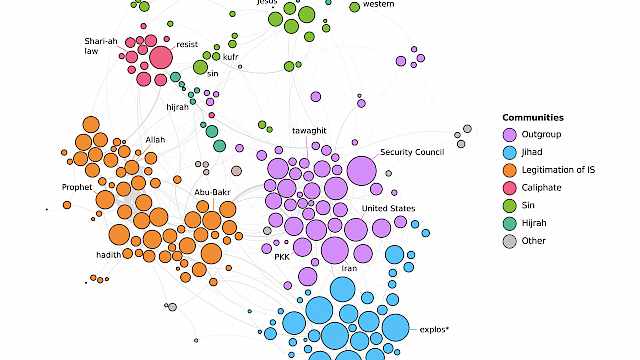

Periods of change can be important crucibles for trust and distrust. Change disconnects people from their previous employment roles. It alters their relationships with close colleagues through whom their organisational identity is nested. More insidiously, the way change is managed can expose inequalities and inconsistencies leaving those affected feeling less committed. Transformations can create the emergence of internal threats to organisations, as longstanding employees become disgruntled, angry and sufficiently disengaged to behave in counterproductive ways as a form of redress, or worse, revenge.

Trust, therefore, is to a large extent derived from the past, a bit like driving by looking in a rear view mirror, which is fine as long as the road remains the same

Suddenly model employees can become distrustful. These behaviours can be small-scale such as time-wasting, or more serious insider threat activities such as destroying systems or leaking confidential information; they must therefore be considered within a broader context of the threat to wider publics and national security. So how can organisations stay secure during times of change? From our research, we propose that understanding better the elements which support trust development, maintenance, and its repair will avoid these shifts to distrust.

Recent studies have shown control systems complement trust. Input controls provide re-assurance determining who enters the organisation, while output control covers what is done. Process controls concern how things are done, allowing employees to better navigate their way and creating consistency across different components of large organisations. Finally, sanctions and punishments show the seriousness directed at those who deviate. Transparent and fairly-used controls are enhancers of trust levels. Employees pick up clues and signals about organisations and their key agents during the course of their employment. While those at the top of the organisation are important, the line manager plays a critical role in such signalling.

Line managers who lack competence emerge as less of a liability for trust than those without integrity. They are important in promoting positive work attitudes, enhancing job satisfaction, reducing decisions to quit, and increasing organisational citizenship and commitment. Even more security is gained through ensuring an employee feels trusted by their line manager. Co-workers also play an important role, they share insight and create a group level perspective on the local and wider organisation.

The implications for organisational managers is that, particularly during times of uncertainty or change, attention should be devoted to managing expectations through clear and ongoing communication. This includes, perhaps paradoxically, being transparent about when and why it might not be possible to be fully transparent. Leaders must pay as much attention to making organisational decisions in a fair manner, as to the outcome of the decision itself. As responsible members of organisations, we can all learn more about our colleagues and employees by being vigilant to individuals’ emotions and the behaviours which may exhibit warning signs of threat. All of this can be done by enacting both cognitive and affective trust and by considering what signals we send employees both in times of stability and in change.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)