The purpose of the majority of investigative interviews is to elicit the most detailed, accurate, and complete accounts from the interviewee. With that in mind, being able to establish what happened and who did what is a vital skill and this derives from following effective interviewing practice. Detailed and reliable information is so important to investigations because it helps inform investigative decisions: the better the information, the better the decisions. However, it is important that information should not be obtained ‘at any cost’. Interviewing needs to be ethically conducted in order to obtain information that is legally, and indeed factually, reliable. As research has shown, the history of police interviewing in England and Wales has seen the consequences of unethical and ineffective practice and the resultant unreliable evidence that follows from these practices.

How research changed interviewing

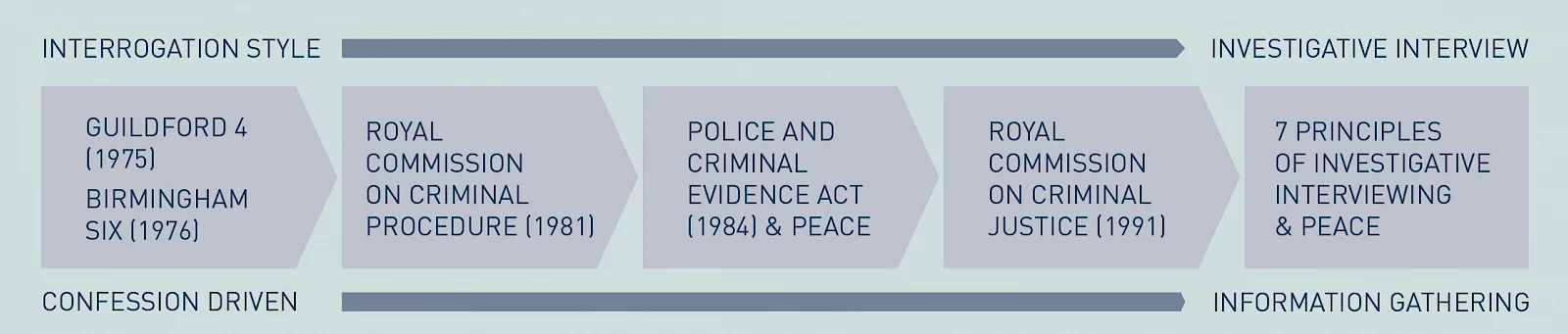

The concept of a successful interview has changed hugely since the 1970s. Prior to the early 1990s, no formal interview training was provided to police officers across England and Wales, as back then trainees were expected to learn by observing experienced colleagues. Often these experienced colleagues promoted methods which were purely focused on getting a confession, as gaining a confession was perceived to be a successful interview. However, methods like these contributed to cases such as the Guildford Four (1975) and Birmingham Six (1976) which are prime illustrations of how unethical interviewing can lead to miscarriages of justice. The public outcry which followed the overturning of those verdicts led to the integrity of police interviewing practices being questioned.

Police interview practice has developed over time, hand in hand with research. A milestone was the 1984 Police and Criminal Evidence Act, which mandated the recording of suspect interviews. For the first time, researchers were able to conduct an in-depth analysis of police interviews with suspects, published by the UK Home Office in 1992. This highlighted serious shortcomings, including lack of preparation, poor technique and assumption of guilt, in more than a third of police interviews. The report led directly to the development of a UK national framework of interviewing (PEACE).

The PEACE framework outlines the phases of the interview:

- Planning and preparation – where to hold the interview, what is known about the interviewee and what needs to be proved?

- Engage and explain – explain what the interview is for, engage the interviewee in a conversation

- Account, clarification and challenge – use open questions, allow interviewee to explain their account

- Closing down the interview – summarise the account given and explain what happens next

- Evaluation – evaluating the information received, the interview process itself and the performance of the interviewers.

While the general focus of investigative interviewing has improved since the introduction of PEACE, this impact appears to be primarily concerned with the more procedural and legal aspects of the interview rather than the more complex interviewing skills required. Aspects of investigative interviewing remain demanding for interviewers, such as how to challenge accounts in a non-confrontational but useful way, and these skills need to be maintained through repeated training.

Where research is helping now

Research continues to analyse and improve interviewing techniques. This includes work on the role of interpreters, on how cultural differences can affect the information offered by interviewees, and new techniques for uncovering deception. While these may not have such a seismic impact as the improvements in UK police interviewing approaches in the last thirty years, there is no doubt that the continued interaction of researchers and interviewing professionals is a positive and productive partnership.

Read more

- Read more about the PEACE framework here: https://www.app.college.police.uk/app-content/investigations/investigative-interviewing/

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.