An investigative interview is a dynamic relationship. Both interaction partners, interviewer and interviewee, change the course of the conversation by each thing said, every piece of information given and all the other elements of interaction.

Rapport plays a crucial role in investigative interviews. Rapport is the process of building a relationship between the interaction partners and is characterised by trust, mutual attention, and coordination. But rapport seems to be poorly understood and there is no way to efficiently measure rapport (yet). So far, rapport is measured after the interview and from a very subjective point of view. A lot of information is missed.

Still, given the importance of rapport, my research seeks to establish a novel measure that can do exactly that: measure rapport when it occurs and in real-time. With this knowledge, we are one step closer to understand, efficiently build and to maintain rapport.

What has nonverbal behaviour got to do with rapport?

To understand rapport, one must understand the dynamic relationship between the interaction partners during an investigative interview. The complementary roles that verbal and nonverbal behaviour play in an interaction are long recognised but little is known about how verbal and nonverbal mimicry happen, nor how these relate to building rapport and cooperation between the interview partners.

People tend to mimic each other when they interact. Mimicry happens on both sides at once and that makes it even more fascinating. Both interaction partners mutually influence one another. If mimicry occurs both partners will feel more in sync which leads to a feeling of having bonded. This bond is crucial when it comes to sharing information.

Little is known about how verbal and nonverbal mimicry happen, nor how these relate to building rapport and cooperation

Most of the time, both nonverbal and verbal mimicry show subconsciously. But here it gets interesting: while the sender might not even be aware they are sending subconscious messages, the receiver can still pick up on them. In other words, some of the conversation lies beyond what is said out loud – in speech and movement.

For example, it could be the case that interviewers show more body movement when interacting with witnesses who are not cooperative during the interview. We use more nonverbal behaviour when verbal messages are exhausted. You can observe this in everyday life: You struggle to remember a name, a word; it’s on the tip of your tongue and your hands try to help you to remember.

How to use mimicry as a measure of rapport?

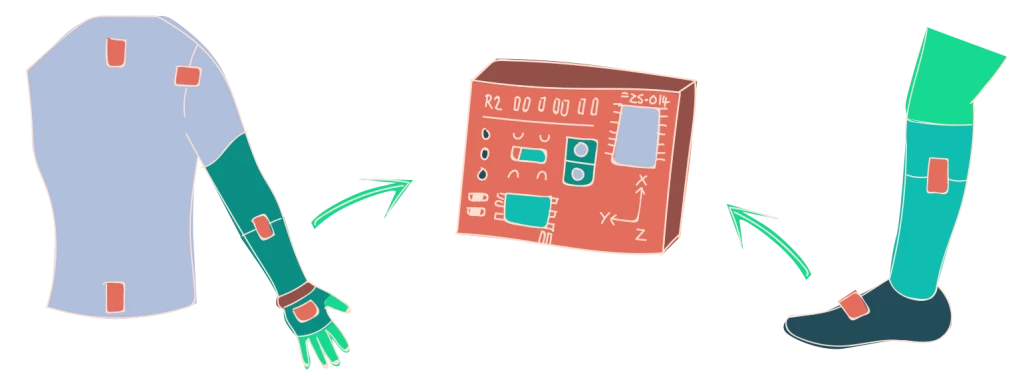

In my studies, I will use motion tracking suits to record nonverbal behaviour. These suits have been used numerous times in human interaction research. They provide information about human body movement that goes beyond data that is coded by a human from a video recorded interaction – the data are objective and accurate.

The suits involve nine matchbox-sized sensors that are attached via straps on the participant. These sensors measure body movement and its direction with high precision. The suits allow us to measure the level of movement that shows usually during an investigative-style interview.

The main goal is to detect even slight changes in the natural flow of human interaction. With the help of this technology, we can observe when the interview partners are in sync, and therefore most likely developing rapport – this gives us the opportunity to measure rapport in real-time.

How is this research useful?

There are promising implications of this line of research.

Using it, we hope to explore how different motivations and goals influence the experienced rapport and what impact different motivations and goals have on interview effectiveness. It helps us define what rapport is and how it shows. We won’t have to rely on interviewers subjective feelings about when rapport is established and can instead measure and understand rapport as a dynamic construct, establishing a novel objective measure for rapport in real-time.

In the future, interview training could soon use virtual reality, giving the trainee the opportunity to experience various realistic scenarios. This would be an efficient way to train interviewers without using scripted and rigid manuals of how to build rapport.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)