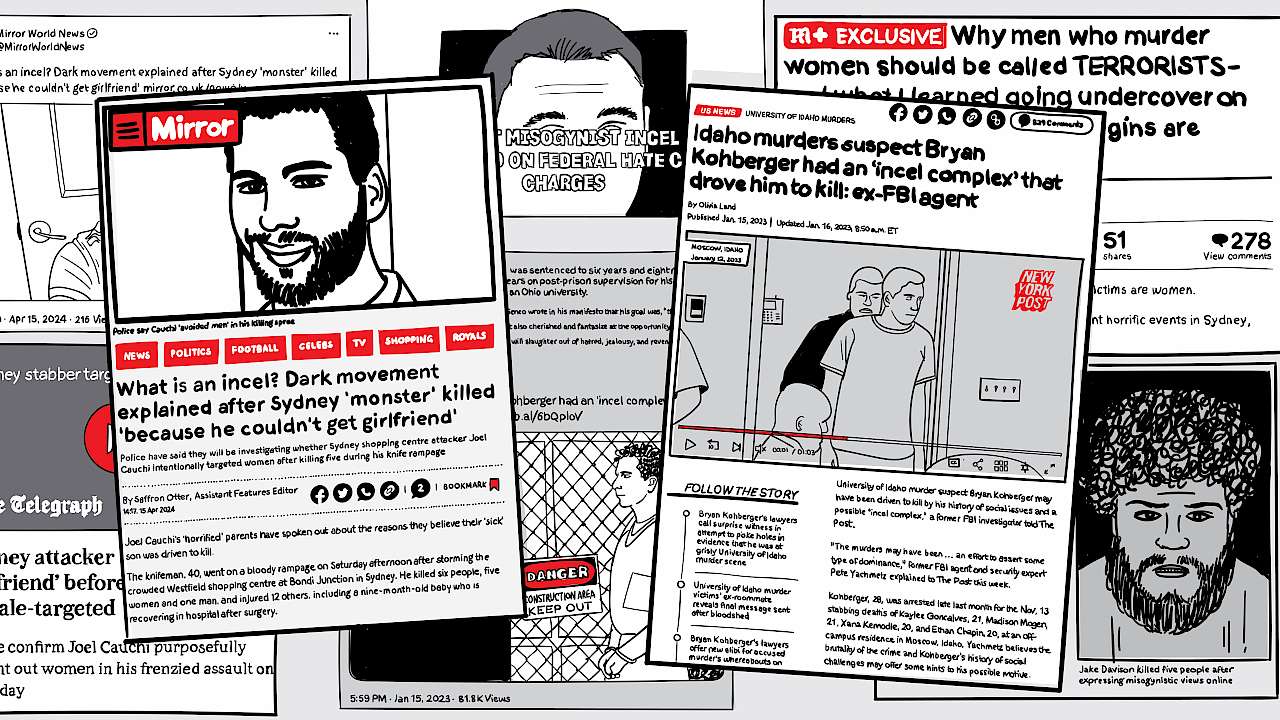

Incidents of misogynist violence are often tenuously linked to the wider incel community in media reports, most notably in the immediate aftermath of attacks carried out by lone male perpetrators. Recent cases of misogynist violence, including the murders of four University of Idaho students in their off-campus residence in November of 2022 and a mass stabbing at the Westfield Bondi Junction shopping centre in Sydney earlier this year, have been described by some news outlets as clear cases of ‘incel-related’ violence.

This article offers three critiques of the speculative narratives linking misogynist violence to incels in the immediate aftermath of an offline attack, closing on tangible suggestions for reporting on cases of misogynist violence.

Misogynist Inceldom versus Involuntary Celibacy

The term incel – short for involuntary celibacy – is a self-ascribed identity for anyone, regardless of gender and sexual orientation, experiencing the temporary life circumstance of unwanted singlehood. The term itself is rooted in inclusivity and queerness, stemming from an online forum first developed by a queer Canadian woman named Alana in 1997 to help support people experiencing inceldom. In recent years, the term has become synonymous with a vocal subset of cisgender, heterosexual men in fringe online spaces who spread male supremacist ideologies and use aggressive, violent speech towards women in their posts. Media reports often use the broader term incel to refer to the misogynist subset of this community, without making the distinction between misogynist incels and the wider identity of involuntary celibacy.

It is important to note that people of all genders and sexual orientations can – and still do – identify as involuntary celibates: they find solace in a term to name their experiences with unwanted singlehood, but distance themselves from the contemporary misogynist branches of the community. Differentiating between misogynist incels – those who weaponize male supremacist beliefs and language – and the broader self-ascribed identity of incel allows for recognition of the nuances within the wider incel community, while centring the misogynist community members specifically within wider discussions of misogynist violence.

Media reports often use the broader term incel to refer to the misogynist subset of this community, without making the distinction between misogynist incels and the wider identity of involuntary celibacy.

Who Counts as an “Incel-Related Attacker”?

While attempts have been made in the academic literature to classify “incel-related attackers”, uncertain thresholds for proof of incel status and the lack of a cohesive conceptualisation of “incel-related ideology” add complexity when attempting to decide whether an attack can be definitively connected to misogynist inceldom. Shared grievances about women and feelings of resentment over romantic rejection unite spaces across the Internet manosphere, making it difficult to parse which beliefs – if any – are truly unique to misogynist incels alone.

Similarly, varied levels of participation in online misogynist community spaces and uncertainty around whether perpetrators self-described as an incel also impact potential classifications of misogynist incel violence. Celebrating perpetrators of mass violence is common within misogynist incel forums, with users anointing lone male perpetrators of contemporary and historic acts of violence with titles of ‘saint’ or ‘martyr’. Despite this, several of the perpetrators of mass violence heralded as deities by some misogynist incels have no direct ties to community forums or the label itself, further muddying attempts at clear classifications.

Obscuring the Realities of Mainstreamed Male Supremacism

Narratives that connect cases of misogynist violence to inceldom alone obscure the realities of male supremacism, which is entrenched and supported through the social, political, and economic structures within patriarchal societies. Moreover, regressive ideas about women and anti-feminist backlash are increasingly platformed throughout mainstream social media platforms, with male supremacist ideas seen in fringe communities on 4/8Chan, Gab, and KiwiFarms now permeating through to TikTok, Twitter/X, Instagram, YouTube, and Reddit. Misogyny influencers like Andrew Tate, Jordan Peterson, and Joe Rogan, alongside popular masculinist pod/vodcasts, platform male supremacist ideas about women and feminism that are similar to those held by misogynist incels, as well as other communities across the Internet manosphere.

Focusing solely on misogynist incels as the cause of misogynist violence may limit opportunities to acknowledge the mainstreaming of male supremacist beliefs across platforms, and to explore how this violence is linked to broader social and societal structures of oppression.

Recommendations for Responsible Reporting

In order to better report on and contextualise cases of misogynist violence, journalists may benefit from:

- Avoiding tenuously linking mass violence to misogynist incel communities based on potential characteristics of the perpetrator, including mental health challenges, struggling with rejection, and resentment toward women. These are not unique to misogynist incels alone and are common factors across cases of male supremacist violence.

- Using precise language when speaking about male supremacist communities. Adopting the term misogynist incel(s) instead of incel(s) helps differentiate the ideological community from the wider self-ascribed label of involuntary celibacy.

- Contextualising attacks within wider cultural climates of male supremacism, extending beyond misogynist incels as the sole cause of misogynist violence.

Read more

Alana (1997). Online forum: Love Not Anger: Beyond involuntary celibacy. Available at: https://www.lovenotanger.org/

Czerwinsky, A. (2024). Misogynist incels gone mainstream: A critical review of the current directions in incel-focused research. Crime, Media, Culture, 20(2), 196-217. https://doi.org/10.1177/17416590231196125

Land, O. (2023). Idaho murders suspect Bryan Kohberger had an “incel complex” that drove him to kill: ex-FBI agent. New York Post. https://nypost.com/2023/01/15/idaho-murders-suspect-bryan-kohberger-had-an-incel-complex-that-drove-him-to-kill-ex-fbi-agent/

Otter, S. (2024). Incels explained after Sydney “monster” killed “because he wanted girlfriend.” The Mirror. https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/world-news/what-incel-dark-movement-explained-32588848

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)