This report is divided into eight sections:

- History, demography, and communities

- Mosques

- Families, gender, and generations

- Education

- Transnational connections

- Islamic movements and networks

- Representative, civil society, and campaigning groups

- Cultural, secular, and ex-Muslims.

History, demography, and communities

There have been Muslims in Britain since the 16th century, with communities developing from the late-1900s in the port cities of London, Cardiff, Glasgow, Liverpool, Tyneside, and Hull.

Major Muslim populations in the UK have their origins in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Yemen, and Somalia.

Following migration from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) in the 1950s and 1960s, South Asian Muslims settled in the major industrial towns and cities of the Midlands, northern England, and parts of London, particularly Tower Hamlets.

Civil wars and political unrest in Africa, the Middle East, South Asia and Eastern Europe since the 1980s resulted in the arrival in the UK of asylum seekers and refugees, including Muslims from Algeria, Libya, Somalia, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Bosnia.

There is a long history of conversion to Islam in the UK, including early seafarers and elite converts from the mid-19th century, to those who married migrants in the 1950s and 1960s, and more recently to those who have converted for personal spiritual reasons.

In 2011, there were about 2.8 million Muslims in the UK. Under 5 per cent of the population of England and Wales was Muslim; in Scotland the figure was 1.4 per cent.

Nearly half the UK’s Muslims were under 25 years old in 2011.

On education and employment issues, the 2011 population census showed an improving picture of attainment and progress for British Muslims compared to 2001. There was evidence of a ‘Muslim penalty’, however, for both women and men, as a result of the impact of Islamophobia.

In three separate scenarios, the US Pew Research Centre projected the Muslim population in the UK in 2050 to be 9.7 per cent (zero migration scenario), 16.7 per cent (medium migration scenario) and 17.2 per cent (high migration scenario).

British Muslim communities are characterised by religion, kinship, language, and ethnicity. Research has often focused on Muslims from a single ethnic group settled in a city or neighbourhood, e.g. Yemeni Muslims in South Shields or Bangladeshi Muslims in Tower Hamlets.

Muslim differ from one another historically, socially, politically, and demographically. They are internally differentiated too, for example by religious sect, political faction and generational differences.

A major problem for Muslims in the UK has been the way they have been perceived by others. Anti-Islamic sentiment has a long history in Europe, but Islamophobia (fear and dislike of Islam and Muslims) has been especially pronounced since 9/11.

In popular discourse Muslim communities are often associated with conflict, oppression, extremism, and terrorism. Reports of hate speech and physical attacks have increased.

There is a long history of research on Muslims in the UK. Researchers have differentiated Muslim communities on the basis of national or ethnic origin, areas of settlement, and sectarian identity. Research on young Muslims has become important in recent decades.

Mosques

85 per cent of British Muslims are Sunni; 15 per cent are Shi‘a. South Asian and Middle Eastern Islamic reform movements remain important for the identity and management of mosques.

In 2017, there were 1,825 mosques in the UK. The majority were associated with South Asian reform movements (72 per cent). Drawing on Middle Eastern traditions, 9 per cent were Salafi, with 3 per cent representing mainstream Arab or African Sunni Islam. Around 6 per cent were run by and for Shi‘as (including Ismailis). The remainder were non-sectarian prayer rooms.

In 2017, 72 per cent of mosques had facilities for women, though the nature and extent of these varied.

Mosques provide space for daily prayer, the weekly Jum’a and other community gatherings. They are an important social and sometimes political hub, They offer Qur’an classes for children, and the larger ones host Shari‘ah Councils.

Internal mosque disputes concern management and election issues. At times, conflicts also take place between neighbouring mosques or mosques of different sects.

Mosques have become a target for hate crimes.

Although many mosques are religiously conservative, few have been linked to jihadist networks, a key exception being Finsbury Park Mosque in north London.

The suitability, training, and standards of mosque leadership have been discussed by Muslim communities and Government. A Muslim Faith Leaders Review was published in 2010.

Family, gender, and generations

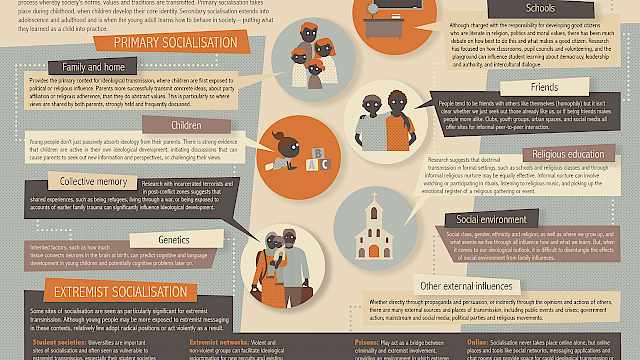

The family is important for religious and cultural socialisation, and the home is an environment where norms and values are shared and reinforced, including those relating to gender.

Kinship structures and traditions vary according to country of origin and exposure to western society and culture, but tribe and clan arrangements and transnational ties remain important, especially for the first generation of migrants.

Kinship relationships had an impact on the migration process. They affected where families chose to settle, and often where men worked, as well as with whom they socialised. Extended families were bound together by a ‘gift economy’, through the exchange of marriage partners as well as material goods and favours in the UK and back home.

Marriage in Islam is a solemn civil contract between a man and a woman. For most couples marrying in the UK, both a civil and an Islamic marriage is undertaken, the former being a state requirement and the latter a religious and social custom.

Most British Muslims marry within their own ethnic group, and many from South Asian families still marry a blood relative. Most young Muslim women, however, express a preference for marrying a Muslim from the UK on the grounds that they will be more compatible.

Fewer marriages are arranged solely by parents, though parental approval is generally sought. British Muslims are getting married older than previously, often after graduating and moving into work, and some are choosing ‘Islamic marriages’ rather than arranged ones.

Muslim marriage and divorce in the UK have come under increasing public scrutiny, with forced marriage and sham marriage criminalised, and underage marriage, polygamy and the role of Shari‘ah councils receiving media attention.

A minority of Muslim homes have separate spaces for men and women. In general, self-segregation is only practised when visitors who are not close family relatives are present. The home is often referred to as the domain of women and children, as opposed to public space which is seen as male. Nevertheless, Muslim women of all ages can be found in universities and colleges, workplaces, shopping malls, public transport, and in mosques.

Muslim women in the UK continue to be less economically active than men, although their participation in the labour market and in higher education is increasing.

Muslim women take roles as prayer leaders and teachers of other women, active civil society organisers, and charity fundraisers. They have campaigned for more inclusive mosques and against violence against women.

Muslim women in the UK have been the subject of academic research and wider public debate, but discussion of their identities has too often focused around the subject of veiling.

Male gender issues are under-researched. Common stereotypes of British Muslim men mask diverse masculinities, based on religion, class, educational achievement, and other variables.

There are significant generational differences in British Muslim communities. Religiously-minded young people have often been attracted to a culturally unadulterated form of Islam, and criticise their elders for a narrow focus on ethnic culture and traditions.

Education

There is a rich tradition in Islam of educational thought and practice. Education is held to cover individual development, the transmission of knowledge, an understanding of social and moral conduct and God-consciousness.

Family and home are where children learn to be Muslims. They are where the primary stage of socialisation takes place, in which they acquire and internalise cognitive and embodied knowledge, practices, skills, and traditions. This early stage of education may also be influenced by religious organisations and by minority-consciousness.

Muslims have in some respects been more successful than others in the UK at passing on their religious beliefs and practices from one generation to the next. Higher rates of intergenerational transmission have been found among Muslims than among Christians, those of other religions, and non-religious people.

Most Muslim children in the UK learn to read the Qur’an in Arabic, whether they do this at a daily mosque school, at the home of an independent teacher, in their own homes or even on Skype. In addition to the Qur’an and Arabic, many Muslim supplementary schools offer other aspects of Islamic Studies, as well as formal instruction in an ethnic language and culture.

Despite calls by parents for a variety of state school accommodations to be made over modesty issues, food, holidays and timetabling, the curriculum, and the provision of single-sex education, the responses of local education authorities have been inconsistent and sometimes confused.

Although most parents send their children to state-run non-religious or Christian schools, some prefer Muslim schools which offer a faith-based Islamic education.

The first state-funded, voluntary-aided Islamic faith schools were established in 1998. By 2015, there were ten primary schools and eleven secondary schools of this kind in England. There were approximately 150 Muslim schools in total, the vast majority of which were independent.

The rising number of Islamic schools and other schools with a Muslim majority has raised questions about social divisiveness, segregation, extremism, and the risk of radicalisation.

Between 2001 and 2011, there was a reduction in the percentage of Muslims with no qualifications, an increase in the percentage of women participating in higher education, and the number of Muslims with a degree-level qualification more than doubled.

University or college offers the opportunity for young Muslims to experiment away from family, community and mosque, and to forge their own identity.

Islamic extremism on campus is considered a problem by higher education systems around the world, including in many Muslim nations.

Whilst some British Muslim students have expressed concerns about student Islamic societies and their politics, they have also felt targeted by Government (as a result of the Prevent duty) and by the negative reporting of media and think tanks. They have complained that their positive contribution, critical judgement, and charity work have been ignored and that they have been implicated in the activities of an extremist minority.

The extent to which university campuses and student societies are open to the risk of radicalisation and extremist infiltration has been a matter of debate. There have been cases of Islamic Societies providing platforms for the expression of extremist views, but there has been no evidence that students have been radicalised as a result of this.

Some Muslims study at Islamic seminaries or dar al-‘ulum. There are now more than 25 registered seminaries, most catering for male students, though several are female-only, and a number are now co-educational. Many are still conservative and traditional, but others have sought to engage faith with modernity and to prepare their students for academic and religious leadership in secular contexts as well as mosques.

There have been improvements to imam training, and attempts have been made to connect Islamic seminaries to the higher education sector.

Studying at a dar al-‘ulum remains a cheaper alternative than further and higher education. As yet there is no Islamically acceptable loan system for those Muslim students and their families who eschew interest-based loan arrangements for the repayment of tuition fees.

Transnational connections

Islam has been described as a travelling faith. In addition to the Hajj, British Muslims may make visits to Sufi shrines, Shi‘a mosques, or sites associated with the Prophet Muhammad, in the Middle East or South Asia. Religious travel is important both as an individual spiritual commitment and as a communal practice.

Some British Muslim communities have active transnational links with their countries of origin, involving regular family visits, the sending of remittances, marriages, and religious and political ties.

Other British Muslim communities are conscious of diasporic memories and cultural connections, but their practical ties have been severed by war or conflict, and by family displacement and dispersal.

Many second and third-generation British Muslims have espoused a universalising Islam which they believe transcends culture and ethnicity, one which accords with their more cosmopolitan consciousness.

British Muslim communities use a wide array of media and information technology to communicate with family and friends and to stay in touch with political and religious events in their countries of origin or elsewhere in the diaspora.

The first generation of British Muslims made extensive use of ethnic media, including newspapers, radio, and satellite TV, in Urdu, Punjabi, Bengali, Turkish, and other community languages. Later generations are less familiar with these languages, less directly involved in homeland politics, and more at ease with an English language minority media directed at their needs and interests and with the global Islamic media.

The connections that migrants maintain, to families, diasporic communities and transnational networks, raise development opportunities and security issues for governments and international organisations.

As well as sending money and investing in projects ‘back home’, diaspora communities – including those in the UK – can mobilise quickly in support of a cause, raise funds, exploit social media, lobby political leaders, and use networks to transfer information and resources.

British Muslims have founded charities to provide humanitarian aid and development funding worldwide (including for UK causes) and to collect and distribute the obligatory Islamic alms, zakat. Many young Muslim volunteers are motivated by opportunities for active citizenship and ethical living.

Allegations about links and the provision of support to terrorists have been made but not substantiated.

The move to digital platforms and to social media, while empowering for British Muslims, has raised some security concerns, especially in relation to potential online radicalisation and the recruitment of young people to international jihadi activism. But assumptions about the causal role of the Internet in terrorism are not borne out by the evidence. The internet helps facilitate radicalisation and recruitment rather than causing them.

Some British Muslims have travelled abroad to fight alongside other Muslims in civil, national, or global struggles. Only a minority of these has taken up arms, though; most have stayed in the UK and joined public protests, run fundraising events or distributed aid.

In the 1990s and 2000s, small numbers of British Muslim men travelled abroad to fight, either with compatriots in homeland conflicts, for example in Somalia, or alongside Muslim brothers in civil struggles, such as in Bosnia. From 2012, British Muslims, including women and children, travelled either independently or as part of a network to join those fighting in Iraq and Syria, under the banner of the Islamic State, Jabhat al-Nusra or other jihadi groups.

British Muslims have given various reasons for participating in violent international jihad. Some have been moved by the suffering of Muslims in conflicts abroad, some by the idea of martyrdom and the promise of paradise. Others have sought adventure, or travelled as seasoned foreign fighters. Of those who travelled to join Islamic State (IS), many wanted to be part of the project to build an Islamic state or Caliphate and to live under shari‘ah law.

Islamic movements and networks

Three-quarters of Muslims in the UK consider British to be their only national identity. But some are ‘Muslim first’, seeing religion as more important than other aspects of identity.

In the UK today, a large number of Islamic movements and networks are represented, most with their origins in either South Asia or the Middle East.

In the 1960s, in the initial stages of community development, Muslims in Britain made little reference to different schools of thought or Islamic traditions. Once communities were able to finance and support more than one mosque, traditional divisions began to have an influence. In areas of South Asian Muslim settlement, for example, Deobandis and Barelwis began to establish separate community organisations and mosques.

South Asian reform movements include the Deobandis, Tablighi Jama‘at, the Barelwis, and Jama‘at-i Islami. Although the latter was never formally established in the UK, it generated several organisations, including the UK Islamic Mission, the Islamic Foundation, the Markfield Institute of Higher Education, Young Muslims UK, Dawatul Islam, and the Muslim Council of Britain. Some of these have since cut their ties to Jama‘at-i Islami.

There is a difference between Islam and Islamism, the former referring to the global religion as a whole in all its unity and diversity, and the latter to what is often referred to as ‘political Islam’. In the UK, ‘Islamism’ and ‘Islamist’ have been used generally of groups and individuals informed by the revivalist Islamic movements, Jama‘at-i Islami and the Muslim Brotherhood.

The chief Middle Eastern influences on Islam in Britain have been the Salafi beliefs and practices associated with the 18th-century scholar, Ibn Abd Al-Wahhab (exported by the Islamic regime in Saudi Arabia and by various Wahhabi institutions and scholars). Another key influence has been the Muslim Brotherhood (founded in 1920s Egypt).

Since the 1990s a number of Salafi groups with their roots in the Middle East have appealed to young British Muslims. The principal Salafi movements and trends in the UK include JIMAS, a range of Salafi mosques and initiatives, and radical groups such as Hizb-ut-Tahrir and al-Muhajiroun.

Although Salafi movements share a commitment to reviving ‘authentic’ Islam, their views have differed on issues such as khilafah (an Islamic state or society based on shari‘ah), jihad, and engagement with Government and wider society. Despite being considered extreme in their personal piety and desire to pursue a pure form of Islam, only a small minority have been violent.

The promotion of violence is predominantly associated with nomadic jihadis, such as Abu Qatada, Abu Hamza, Omar Bakri Muhammad, Abdullah al-Faisal, and Anjem Choudary, some of whom had served in conflicts abroad and all of whom used extremist rhetoric sanctioning violence against those they considered to be apostates.

Neither al-Qaeda nor IS were formally constituted in the UK, although their ideologies were disseminated in person by extremist preachers and activists, and online via websites, forums and social media. Despite the absence of a physical base, they were able to recruit and mobilise potential supporters.

Representative, civil society, and campaigning groups

Since the late 1980s, British Muslims have founded Islamic organisations to represent their interests nationally and to work with government and other civil society groups. These have included the UK Action Committee on Islamic Affairs, the Muslim Council of Britain, the British Muslim Forum, the Sufi Muslim Council, the Muslim Association of Britain, the Mosques and Imams National Advisory Board, and the Federation of Student Islamic Societies.

In addition to mosques, Islamic reform movements and Muslim charities, there are several other types of Islamic organisation in the UK: civil society groups, campaigning bodies, and think tanks.

Muslim organisations have been established with diverse objectives in mind, including open debate and discussion, advocacy, campaigning, critique of Government policy, the reporting and recording of anti-Muslim attacks and media coverage, consciousness-raising of gender issues, and countering extremism.

Such organisations are not aligned in their interests or wider relationships; in some cases, they are in competition or dispute with one another. Claims by some that others work too closely with Government are common, whilst others critique those they hold to be extremist or Islamist.

Cultural, secular, and ex-Muslims

Although many young people from Muslim families think of themselves as ‘Muslim first’, not all Muslims are overtly religious. There are many who see themselves as ‘cultural Muslims’, ‘secular Muslims’ or ‘ex-Muslims’.

The term ‘cultural Muslim’ refers to members of the Muslim community who are non-practising but may retain a degree of attachment to Islamic culture and family traditions. It is possible that they account for 75–80 per cent of all Muslims.

Secular Muslims include those whose primary allegiance is to secularism though they may retain an ethnic and even nominal religious identity. One group that represents their interests is British Muslims for Secular Democracy.

A minority see themselves as ‘ex-Muslims’. Some are non-believers or atheists; others have converted to another religion. Those who choose to leave Islam (technically referred to as ‘apostates’) are frequently judged harshly by more conservative Muslims and even by family members, leading some to keep their new identity and views hidden.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)