Purpose and content

The reviews bring together and summarise open source, social science research on ideological transmission. They draw on literature from religious studies, social psychology, sociology, political science, education, anthropology and security studies, and address the following research questions:

- How is political and religious ideology passed on between and across generations and to newcomers?

- Who is responsible for ideological transmission?

- Where and when does ideological transmission take place?

- How do these issues apply to the transmission of extremist and terrorist ideologies?

This report synthesizes arguments and findings from more than a hundred books and articles. It is divided into three principal sections, on the theoretical background, empirical approaches, and case studies on ideological transmission and families in the context of extremism and terrorism.

Definitions

A deliberately broad approach was taken, with ‘ideology’ being understood to include religious and political affiliations, beliefs, values, attitudes, traditions, and practices.

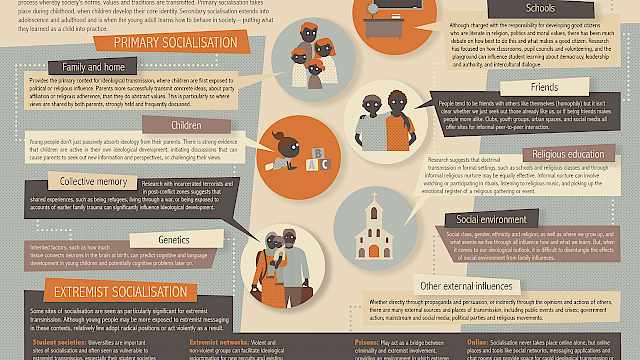

Various concepts were used in the literature for the process of learning and the passing on of knowledge, behaviours, and skills. These ranged from general terms like socialisation, development, and education to more specific ones such as political transmission and religious nurture, and pejorative terms such as inculcation and indoctrination.

Most scholars have focused on inter-generational transmission (principally from parent to child), with increasing interest over time in the intra-generational exchange between siblings.

Religious and political groups have their own ideas about how, when, and where to communicate their worldviews, and on what role the family should play in this.

The direct transmission model

Families in all times and places socialise their children and pass on family culture and the broader traditions, norms, and values of the societies – and in many cases religious and political groups – of which they are part. This process has been discussed by scholars from a wide range of disciplines.

No single, universal model of ideological transmission could be identified in the literature. However, the majority of authors have focused on parent-child transmission. We refer to this as the ‘direct transmission model’.

The starting point of the direct transmission model is that ideology is passed from generation to generation. Much of the early research assumed an effective transmission relationship between parents and children without detailing causal mechanisms.

The direct transmission model has received mixed empirical support. Specific items, such as political affiliation and religious preference, appear to be more effectively transferred between generations. Less concrete items, such as values and beliefs, are less easily transmitted.

The salience of issues, the agreement of parents on matters of belief and value, and shared family practices can boost transmission.

Mothers are more influential than fathers, particularly where they hold strong partisan views or engage in specific parenting styles.

Grandparents and siblings have also been shown to contribute to effective transmission, though this depends on other factors (e.g. whether the family is nuclear or extended, and the closeness of relationships).

Criticisms of the model

A major criticism of the direct transmission model was the assumed lack of agency of children. More recent research has shown that children take an active role in their development, asking questions of parents, forming opinions about parental beliefs, and stimulating debates within the household.

The family may be a major player in ideological transmission, but external influences such as school, political and religious organisations, and the media are also important.

Families influence ideological transmission directly (as above) but also indirectly, as a result of their social class and status, and economic, political, ethnic and religious background.

Religious and political learning and engagement occurs across the life-course, not just in childhood, and may be affected by high-impact events.

Research on intergenerational transmission conducted in stable democracies with white, middle-class, Christian families is unlikely to hold true for different family types and backgrounds, or for those in other contexts (e.g. migration and post-conflict locations).

Different research designs and methods are suited to answering different questions. Quantitative approaches have been used to test ideological similarity between parents and children, and the effectiveness of intergenerational transmission, particularly of concrete concepts. Qualitative approaches have been used to examine how children learn and what they learn within the family, with the focus being on embodied practices and the ‘doctrinal mode’ of learning (through repetition and memory work).

Transmission in non-traditional families and contexts

Ideological transmission is affected by minority status and discrimination. Young people, in particular, may feel they must defend their family or group traditions, values, and practices.

Being part of a transnational family or a diasporic network also impacts on cultural learning both between and within generations.

It has long been assumed that second-generation young people reject the religion of their migrant parents, only for a third generation to return to it. However, many second-generation Muslims, Sikhs, and Hindus in the West have bucked the trend by becoming more religious than their parents and by turning to ‘real’ or ‘true’ religion stripped of cultural and ethnic traditions.

Comparative and cross-cultural research shows that context and family background make a difference. Within a single national context, different religious and/or ethnic groups exhibit differing degrees of success in intergenerational transmission. Across different countries, one factor – income inequality – is seen to predominate in driving religious socialisation.

Evidence from case studies on extremism and terrorism

The cases varied by location, time, group, type of threat and type of source material. Evidence of the role of the family in ideological transmission in these cases was mixed and highly dependent on specific contexts.

The family often played a significant role in a subject’s account of his or her involvement in extremism or terrorism. However, this was rarely presented as a direct transmission of ideology from parents or other family members to the subject him or herself.

In some cases, the family was seen as consciously or unconsciously providing organisational connections to terrorist/extremist groups.

The family was often presented as bound up in a broader historical or political context. Past family experiences or involvement in extremism sometimes provided a source of grievance or encouragement for involvement in violent extremism or terrorism across generations.

In several cases, subjects engaged with terrorist and extremist groups in spite of the objections of their families. At other times, they concealed their involvement from family members.

Three in-depth case studies (of inter-generational, intra-generational transmission, and barriers to transmission) illustrated the often complex relationships between family and terrorism. In no case was ideological transmission via the family seen as wholly explanatory of involvement.

Conclusions

The relationship between the family and ideological transmission is complex. There is some evidence that ideology can pass down through the generations, but this is by no means a foregone conclusion. Many factors can intervene and affect this process, and some items are more effectively transmitted than others.

Evidence from real-world accounts of terrorists and extremists have tended to see the family either as an organisational connector between individuals and terrorist or extremist groups or as a potent source of collective memory, grievance, and tradition. In some cases, individuals adopted the ideological commitments of their parents; in others, they rebelled against them. Some parents shared the grievances of their children, but others criticised and challenged them. In all cases, the role of the family was highly context-dependent.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)