Introduction

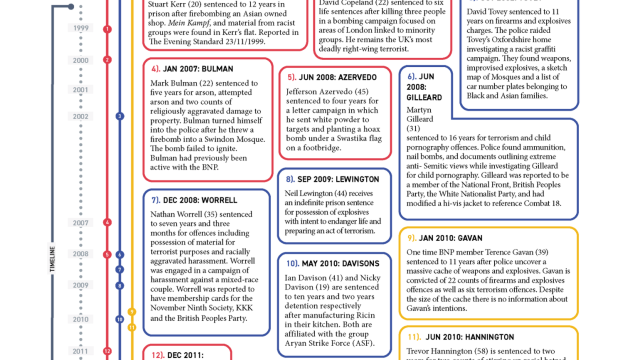

News reporting, legislation, policy, and investigations often contribute to the impression that violent extremists and terrorists are organised, disciplined, and strategic, luring vulnerable young people into distorted worldviews that prize atrocity, hatred, and malevolence. Despite the overt militancy of violent extremist spaces however, actual terror attacks remain rare, and those that do take place are often poorly planned and unaffiliated, or only partially affiliated, to groups. Although some terrorist spectaculars have caught headlines and policy attention, many more attacks and plots are largely ineffectual, never matching up to the violent rhetoric common in these spaces.

(Gelder 2005: 1)

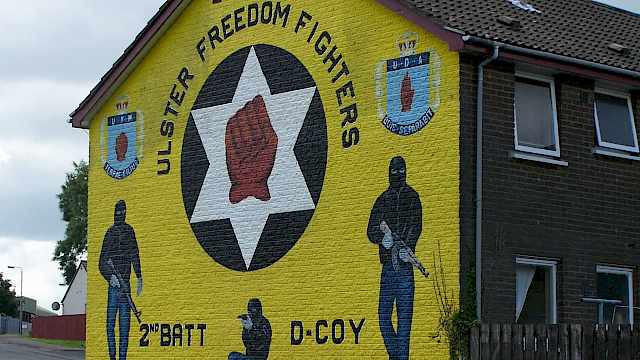

This short report applies subcultural theory to the problem of violent extremist organisation, conceptualising violent extremism as a lethal subculture. Subcultures are traditionally defined as groups of people unified by a deviant perspective; the label is often applied to youth movements such as punks, skinheads, goths, and teddy boys. Lethal subcultures are similarly defined, but with the additional criteria that subcultures either produce or endorse lethal violence as part of their aesthetic or behaviours. A whole range of subcultures could plausibly be included in this category including some aspects of Jihadism, the extreme-right, incels, some skinhead scenes, various youth gangs, criminal subcultures, and so-called dark fandoms.

Theoretical insights in this short report are drawn from a range of disciplines including criminology and cultural studies as well as terrorism studies. This report goes on to suggest that non-violent roles available in lethal subcultures may actually offer some protection against engaging in some violent behaviours by providing access to goods that participants find unobtainable in mainstream society. This may act as a displacement activity, reducing the time and resources available for more violent action.

Key Points

- Subcultures are defined as groups of people unified by a deviant perspective. Lethal subcultures are similarly defined, but with the additional criteria that subcultures either produce or endorse lethal violence as part of their aesthetic or behaviours.

- A range of subcultures could plausibly be included in this category including some aspects of Jihadism, the extreme-right, incels, some skinhead scenes, various youth gangs, criminal subcultures, and so-called dark fandoms.

- There is an extensive history of subcultural studies, but in the context of terrorism studies, subculture has been used a way to explain the emergence of Jihadism in Western context, as a form of status frustration (Cottee 2011).

- This early focus on status frustration has since been critiqued, but the broader stylistic role of subcultures within terrorist settings has been emphasised (Pisoiu 2014; Hemmingsen 2015).

- Jihadist internet activism in particular has been identified as an example of subculture focused activism in which Jihadis online were forced to navigate the tension between advocating for Jihad without participating physically (Ramsay 2012; 2020).

- The term lethal subculture is intended to recognise that alongside the strategic goals of any violent extremist or terrorist movement is a wider subculture with its own values and norms, reflected in its specific uses of subcultural material, internal dynamics, and approach to subcultural capital.

- Overall, despite being only too willing to present themselves as overtly violent and extreme, from a strategic perspective, lethal subcultures have the potential to represent a drag on the violent achievements of extremist and terroristic groups. Actual violence is conducted by a relatively small subset of actors while the majority pursue their own aims and are perhaps distracted by what else the culture has to offer.

Read more

- Atkinson, M., (2005) Tattoo Enthusiasts: Subculture or Figuration, in Gelder, K. (ed) The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition. London: Routledge, pp 326-342.

- Becker, H., (1963) Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: The Free Press.

- Bennett, A. (1999). Subcultures or Neo-Tribes? Rethinking the Relationship Between Youth, Style and Musical Taste. Sociology, 33(3), 599–617.

- Busher, J., & Bjørgo, T. (2020). Restraint in Terrorist Groups and Radical Milieus: Towards a Research Agenda, Perspectives on Terrorism, 14(6).

- Clarke, J., (2006) Style, in Hall, S., and Jefferson, T., (eds) Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in Post-War Britain: Second Edition, London: Routledge, pp147-161.

- Clarke, J., Hall, S., Jefferson, T., and Roberts, B., (2006) Subcultures, Cultures and Class. In Hall, S., and Jefferson, T., (eds) Resistance Through Rituals: Youth Subcultures in post-war Britain. London: Routledge, pp 3-59.

- Cohen, A., (2005) A General Theory of Subcultures, in Gelder, K. (ed) The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition. London: Routledge, pp 50-59.

- Cottee, S., (2011) Jihadism as a Subcultural Response to Social Strain: Extending Marc Sageman’s “Bunch of Guys” Thesis. Terrorism and Political Violence 23(5), 730-751.

- Gelder, K., (2005) Introduction: The Field of Subcultural Studies, in Gelder, K. (ed) The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition. London: Routledge, pp1-19

- Goodwin, M. (2011) New British Fascism: Rise of the British National Party. London: Routledge.

- Griffin, R. (2003). From slime mould to rhizome: An introduction to the groupuscular right. Patterns of Prejudice, 37(1), 27–50. doi.org/10.1080/0031322022000054321

- Hegghammer, T., (2017) Jihadi Culture: The Art and Social Practices of Militant Islamists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hemmingsen, A.-S. (2015). Viewing jihadism as a counterculture: Potential and limitations. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 7(1), 3–17. doi.org/10.1080/19434472.2014.977326

- Laing, D., (2005) Listening to Punk, in Gelder, K., (ed) The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition. London: Routledge, pp 448-459.

- Linden, A., & Klandermans, B. (2007). Revolutionaries, Wanderers, Converts, and Compliants: Life Histories of Extreme Right Activists. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 36(2), 184–201. doi.org/10.1177/0891241606298824

- Macdonald, N., (2005) The Graffiti Subculture: Making a World of Difference, in Gelder, K., (ed) The Subcultures Reader: Second Edition. London: Routledge, pp312-325.

- Malthaner, S., & Waldmann, P. (2014). The Radical Milieu: Conceptualizing the Supportive Social Environment of Terrorist Groups. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 37(12), 979–998. doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2014.962441

- Miller-Idriss, C., (2017) The Extreme Gone Mainstream: Commercialization and far-right Youth Culture in Germany. Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Miller-Idriss, C., (2019) What Makes a Symbol Far-Right? In Fielitz, M., and Thurston, N., (eds) Post-Digital Cultural of the Far-Right. Transcript: Bielefeld, pp123-136.

- Pisoiu, D. (2014). Subcultural Theory Applied to Jihadi and Right-Wing Radicalization in Germany. Terrorism and Political Violence, 27(1), 9–28.

- doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2014.959406

- Ramsay, G., (2012) Cyber-jihad: Ideology, affordance and laten motivations, in Taylor, M., and Currie, P., (eds) Terrorism and Affordance. London: Continuum, pp49-72.

- Sageman, M (2008) Leaderless Jihad: Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Simi, P. (2010). Why Study White Supremacist Terror? A Research Note. Deviant Behavior, 31(3), 251–273. doi.org/10.1080/01639620903004572

- Simi, P., & Windisch, S. (2020). Why Radicalization Fails: Barriers to Mass Casualty Terrorism. Terrorism and Political Violence, 32(4), 831–850. doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2017.1409212

- Thornton, S., (1995) Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Oxford: Polity Press

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)