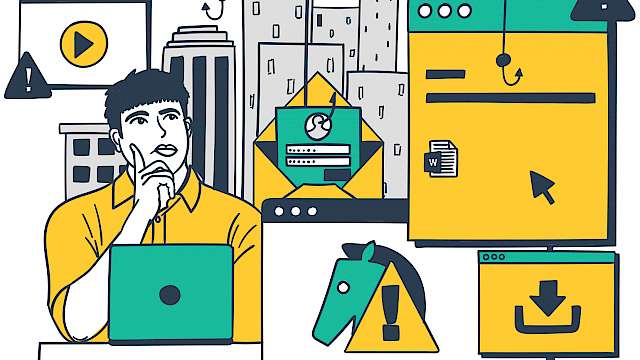

Ninety per cent of cyber breaches involve some form of phishing. As such, it’s increasingly important for today’s organisations to counter phishing risk.

Not only is it important for organisations to know who is susceptible to what kinds of phishing attacks, but they also need to prevent such incidents from occurring.

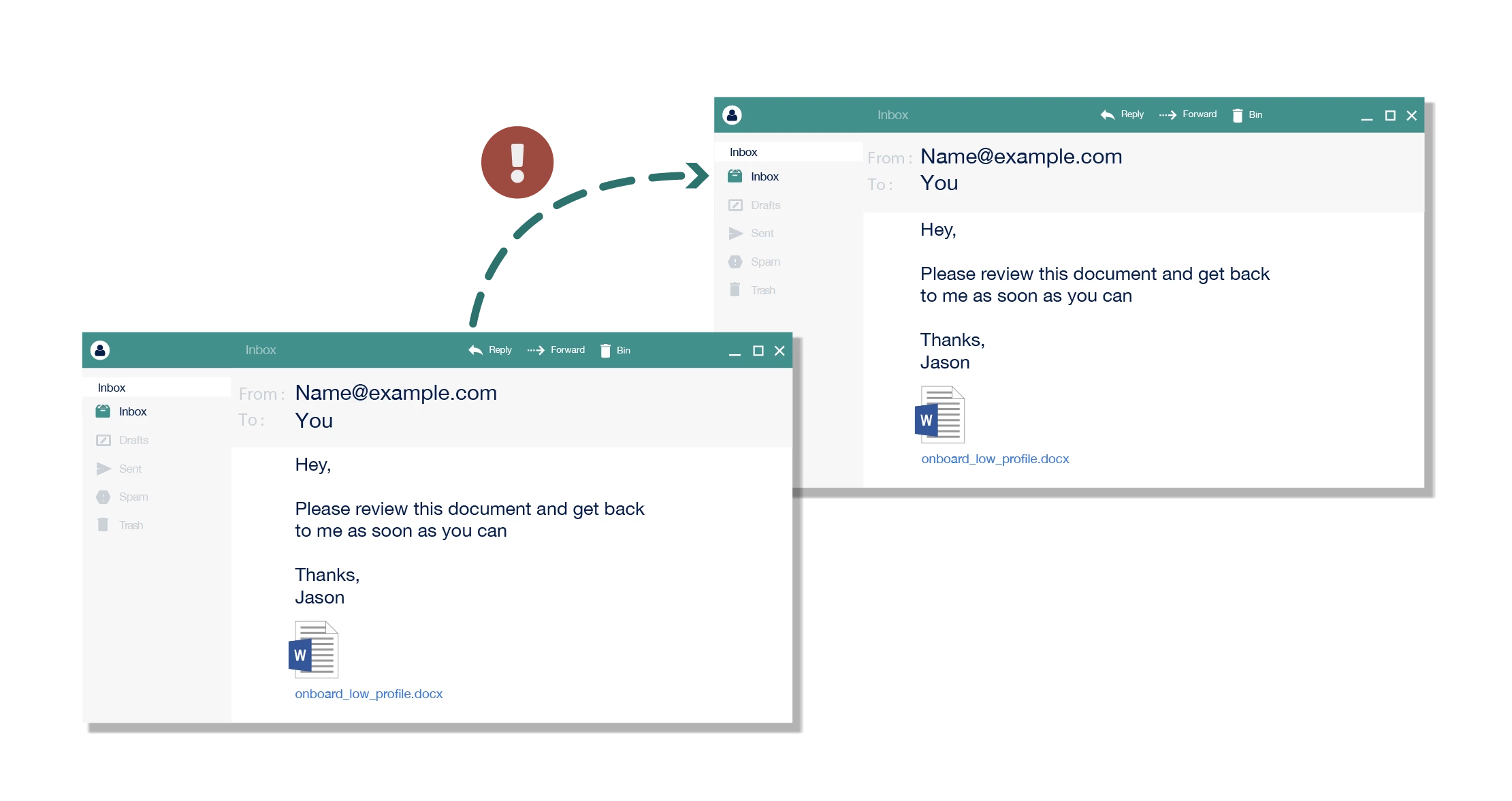

For this reason, organisations conduct simulated phishing exercises, in which they send employees phishing emails that mimic real-world attacks.

The simulations reveal who might be susceptible to certain kinds of phishing attacks. They also provide instant feedback and timely training. Often, those who 'fail' simulations face ramifications.

Simulated phishing is regarded as advantageous over traditional training as it helps users recall information when they need it most, i.e. when they are likely to fall for a phishing attack. There’s also the lure of metrics – simulated phishing campaigns show organisations who clicks and how people behave over time.

Some organisations are beginning to adopt a culture of blame when it comes to phishing their staff.

Still, some measures, such as heavy monitoring and punishing, are concerning. Indeed, some organisations are beginning to adopt a culture of blame when it comes to phishing their staff.

But how do organisations use simulated phishing in practice? What are the training benefits – and unintended implications – of phishing staff?

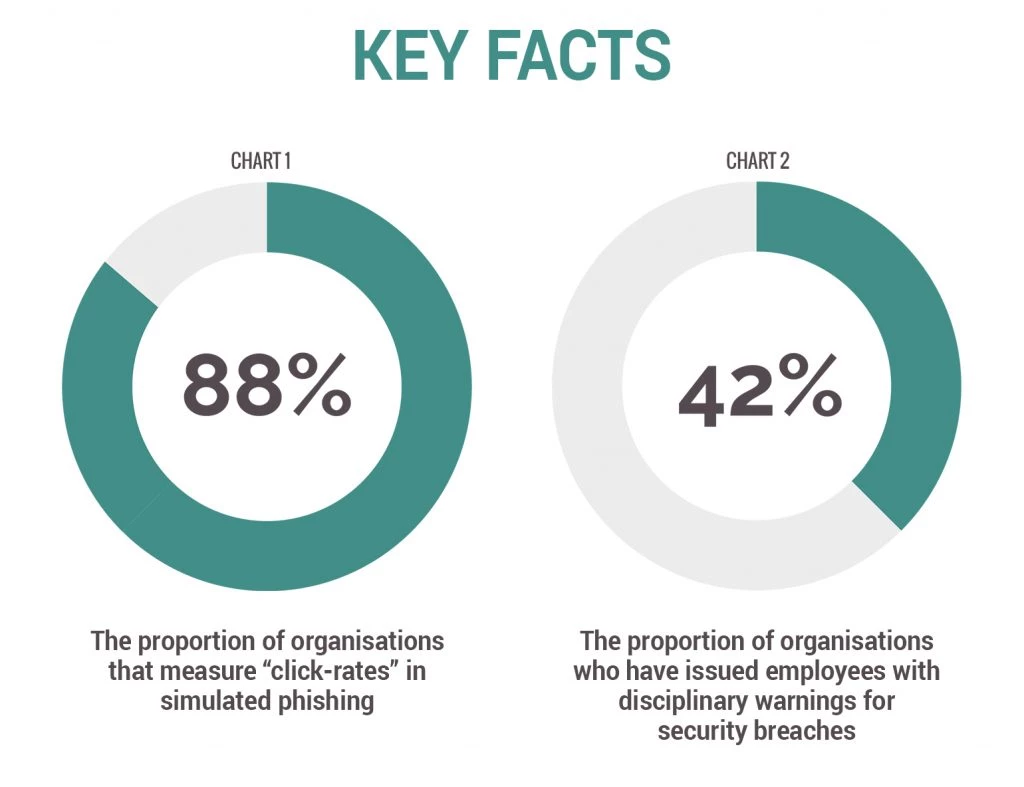

Key facts

Chart 1 shows the proportion of organisations that measure 'click-rates' in simulated phishing – 88%.

Chart 2 shows the proportion of organisations who have issued employees with disciplinary warnings for security breaches – 42%.

Key findings

- Many organisations punish their staff. Punishments range from minor (e.g. compulsory eLearning resits) to severe (e.g. disciplinary measures).

- Circular phishing exists. Organisations regularly re-phish clickers and allocate further, more intensive training (or punishments) for staff who continue to fall for the attacks.

- Simulated phishing leads to behaviour change but enforced training and punishments negatively impact psychological wellbeing.

- Simulated phishing that delivers brief training leads to behaviour change without negatively impacting on psychological wellbeing.

Phishing your staff for behaviour change

Effective simulated phishing should educate people and help them to detect phishing attacks. It should also trigger positive, long-term and sustained changes in security awareness and behaviour.

Scratching the surface, you’ll find that simulated phishing can cause a number of issues. Fear of apprehension and punishment can breed mistrust and resentment. The same fear can stop people from reporting security incidents and reduce people’s productivity.

Our findings suggest that simulated phishing does have training benefits. They also suggest certain types of simulated phishing can damage people’s psychological wellbeing.

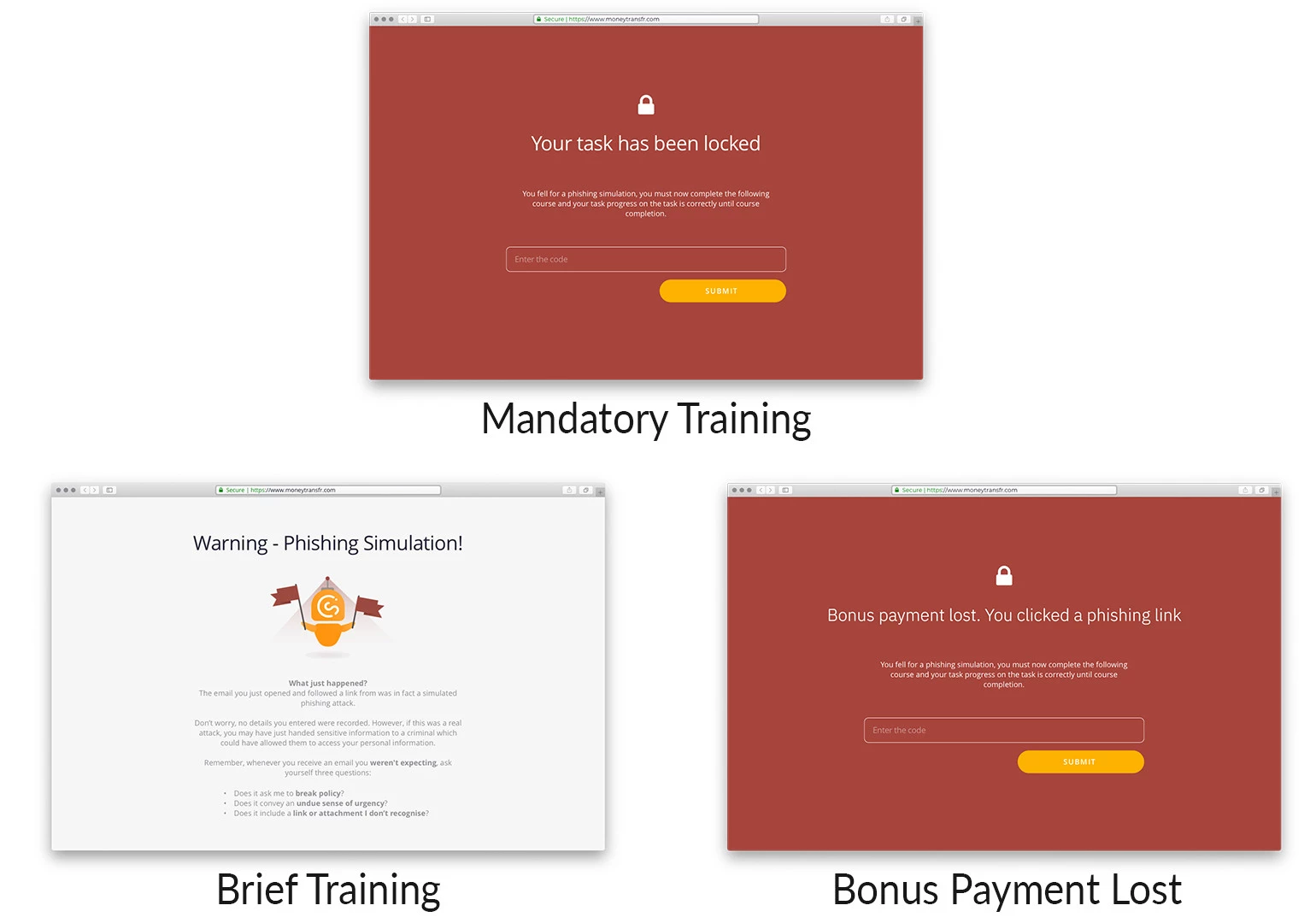

In an experimental lab study, we designed interventions that mimicked real-world outcomes when employees click simulated phishing emails.

The interventions varied depending on the type of training (whether it was a brief message or a mandatory course) and punishment (loss of payment). We looked at the impact on behaviour change, productivity, and psychological wellbeing.

Carrot and stick

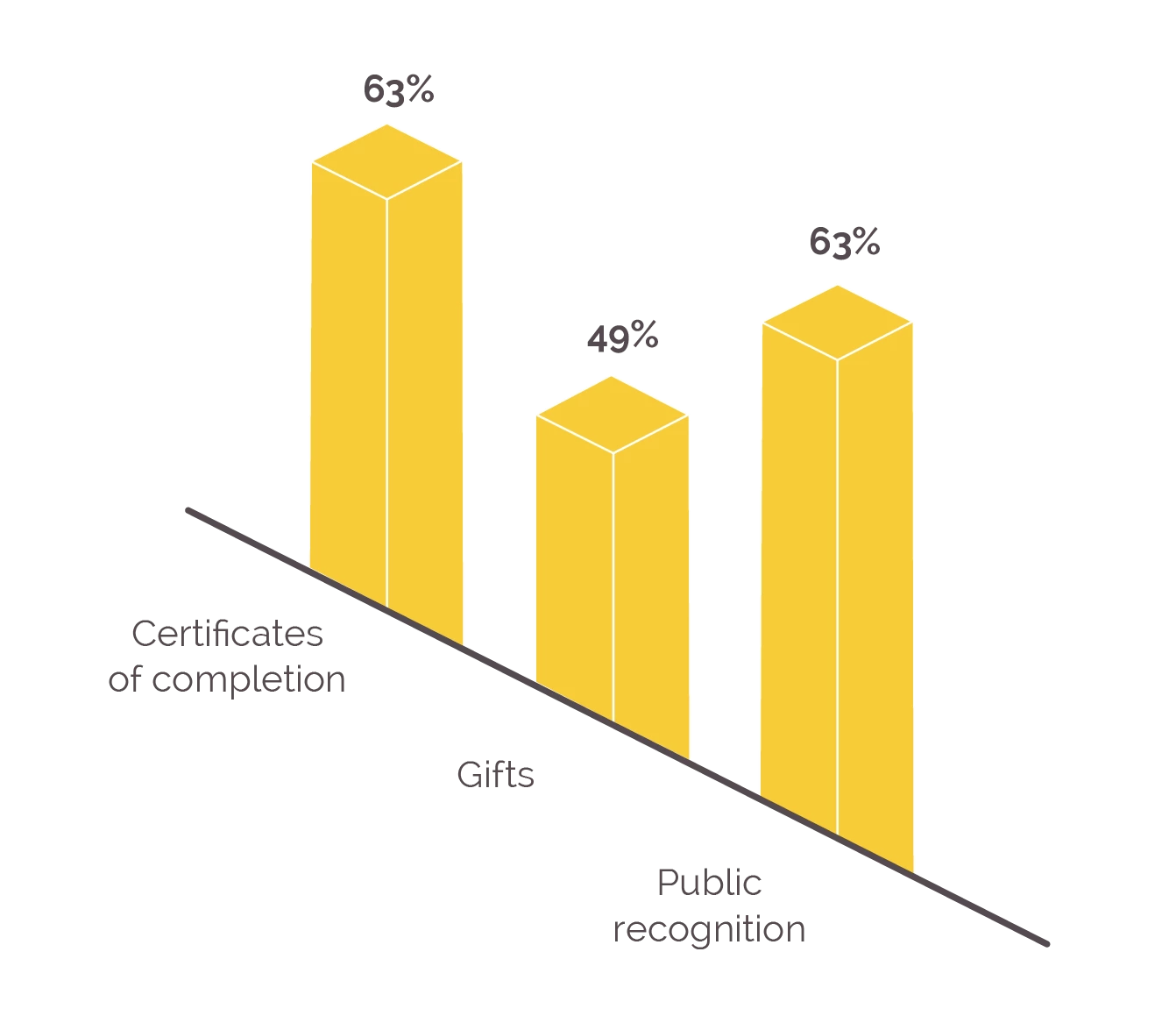

We surveyed how organisations use carrots and sticks in managing human cyber risk (beyond just phishing). We found that organisations favour three rewards:

- Certificates of completion (63%)

- Gifts (49%)

- Public recognition (63%)

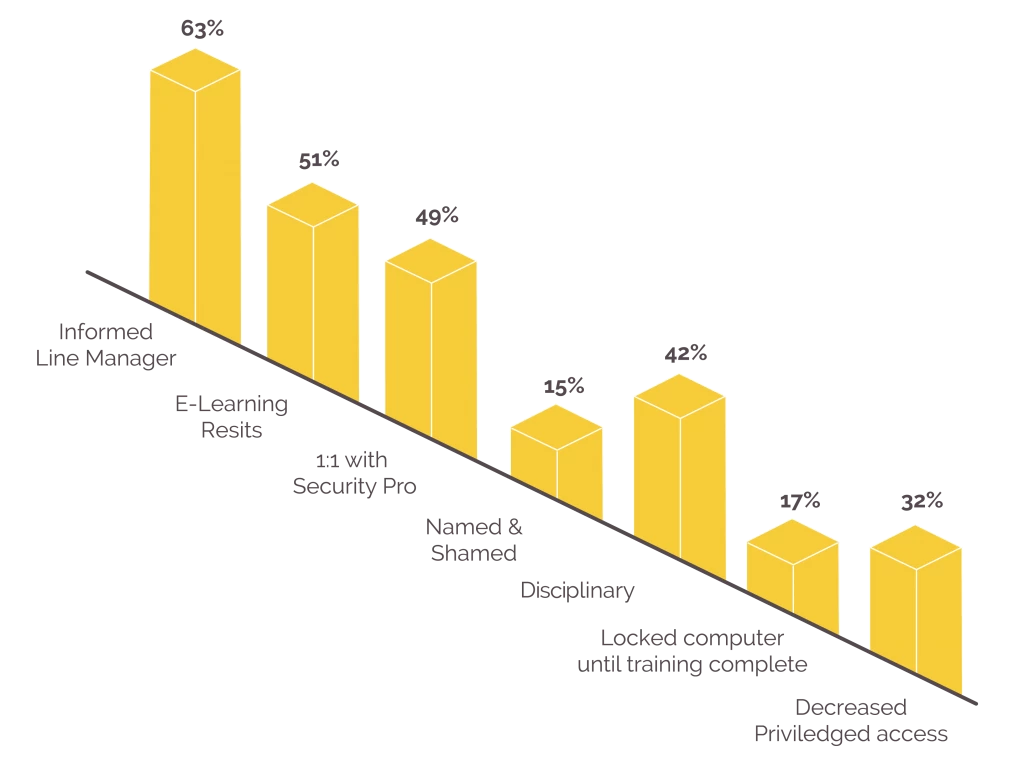

When it comes to punishments, organisational sanctions vary in severity:

- Informed line manager (63%)

- eLearning resits (51%)

- 1:1 with security professional (49%)

- Named and shamed (15%)

- Disciplinary (42%)

- Locked computer until training complete (17%)

- Decreased privileged access (32%)

Compared to a control group, all interventions improved people’s behaviour. However, mandatory training and punishment were not without negative outcomes.

The findings indicate that people view both mandatory training and punishment as (relatively) unfair. Both interventions seem to increase state anxiety which, when experienced long-term, can cause stress.

The findings also suggest that mandatory training inhibits productivity in the short-term.

We conclude that brief simulated phishing training has the greatest benefits. Brief training is seen as fair and reduces phishing susceptibility without denting productivity or causing state anxiety.

Guide to ethical simulated phishing

1. Focus on training benefits rather than 'catching people out'

Let’s drop the blame game. People fall for phishing attacks because they are human and have been trained to click links. That’s a difficult habit to change.

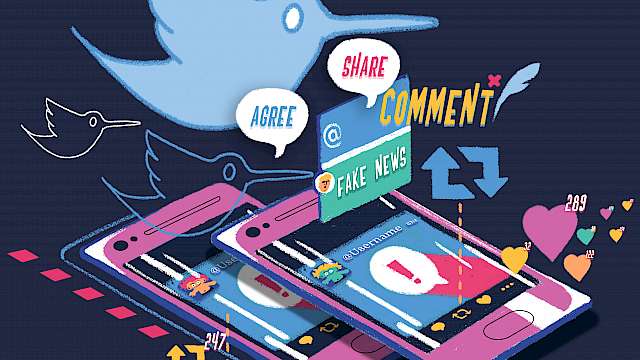

Plus, attackers use social engineering tactics in phishing emails. They might impersonate PayPal, for example, and claim their target’s account is about to be locked – using urgency and fear to deceive.

That’s why phishing emails are so effective. They harness human biases and play on human emotions.

Simulated phishing should develop security skills by giving people timely feedback when they need it.

When we design simulated attacks with a view to play 'gotcha', it undermines their role as a training aide.

2. Don’t run them in secret

Transparency is important. When people are unaware of simulated phishing campaigns, they feel like they’re under surveillance. That makes the security team – the very team you want your staff to turn to for help – the enemy.

Workplaces are all about trust. And trust is a fragile thing. Be clear, open and transparent about the purpose of your approach and what it means for your staff.

3. Make them short and engaging

When people click on simulated phishing links, it’s an opportunity to provide teachable moments. Providing immediate feedback within the context of an attack can help employees to transfer and retain knowledge more effectively. People are more likely to remember how to act when they are faced with a situation similar to when they were trained.

4. Don’t punish, restrict, or coerce

Punishing staff is bad. It’s unfair and reduces productivity. It can lead to stress, distrust, and resentment. It can also lead to legal challenges.

Organisations need people to report attacks, and people are unlikely to report quickly – if at all – when they fear punishment.

5. Focus on the why, not the who

It’s tempting to focus on who clicked a phishing link, rather than why they might have clicked. When we look at the why, we can see which phishing attacks pose most risk. We might learn, for example, that the finance team is particularly susceptible to invoice-based phishing emails. Armed with such detail, we can design better and more personalised awareness and behaviour-change campaigns.

6. Enable behaviour change

Simulated phishing reveals whether or not people report threats. It’s important that we facilitate reporting, such as through 'report a phish' buttons. It’s also important that we give feedback to our staff when they report. Reinforcing good behaviour is key to behaviour change.

Confidence is crucial in security. We need to help people build on their successes!

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)