This report examines public perceptions of counter-terrorism measures in the UK and overseas and brings together evidence on how members of the public, directly and indirectly, experience five specific areas of counter-terrorism policy:

- Schedule 7 and airport security

- Police stop-and-search powers

- Prevent and the Prevent Duty

- Public communications campaigns

- Protective security measures.

It provides examples drawn from the research base which relate to these five policy areas and which are relevant to those working on these issues.

The report also points to important evidence gaps that would benefit from future research, including:

- robust studies that compare experiences across different protected characteristics

- experiences of individuals supported through Prevent and Channel interventions

- direct experiences of police counter-terrorism powers, such as those who are suspected of an offence or who have been stopped under Section 43

- the longer-term impacts that public communications campaigns can have on behaviour

- the impact that such campaigns and protective security measures have on feelings of security and/or fear.

Key findings

Some communities have disproportionately more contact with the counter-terrorism system. Qualitative studies suggest that British Muslims and Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities have disproportionately more contact with the counter-terrorism system and are more concerned about its actual and perceived impacts. While quantitative research suggests that the majority of the British public are unopposed to current counter-terrorism measures, it still estimates that up to one-third of British Muslims distrust the counter-terrorism system.

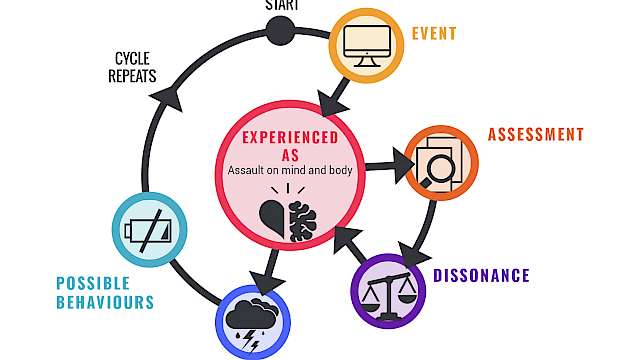

Both direct experiences and indirect experiences, or a broader awareness of incidents where friends, family members, or members of one’s community have had actual or perceived contact with the counter-terrorism system, can have similar impacts. This ‘shadow of the collective story’ can exacerbate perceptions of personal victimisation and can reinforce the view that counter-terrorism measures discriminate against one’s community as a whole.

The effects of having contact with or engaging with the counter-terrorism system extend beyond the individuals involved, with studies finding that families and communities can also be affected.

Official statistics give an incomplete picture of how many people see themselves as having direct contact with the counter-terrorism system. Qualitative research has found that experiences, such as being asked additional screening questions at airports, are often perceived as being related to the counter-terrorism system. Perceived and actual experiences can contribute to a lack of trust in counter-terrorism policies and perceptions of victimisation.

There appears to be a high level of willingness to engage in both formal and informal counter-terrorism efforts under the right circumstances. However, there are still barriers – a lack of trust in the authorities and concerns about discrimination reduce people’s willingness to engage.

There are challenges with ensuring that built environment designers, builders, and operators take protective counter-terrorism measures seriously, although more research is needed to explore how these professionals – including those working in the private sector who design and build structures, and those who work in or manage crowded places – engage with counter-terrorism policy.

More overt counter-terrorism measures can increase feelings of security and safety, but only when the authorities are trusted and perceptions of procedural justice are high.

The counter-terrorism system does not operate in isolation. Concerns about broader discrimination in society, and perceptions that the government is discriminatory, shape perceptions of counter-terrorism policy. Other policy areas that promote equality and social inclusion are therefore crucial for increasing trust in the government and in the counter-terrorism system.

Maintaining and ensuring high levels of procedural justice is crucial for maintaining the legitimacy of the counter-terrorism system, and for mitigating unintended consequences. In order to build trust in the counter-terrorism system, it is important that it is viewed as neutral, treats people fairly and with respect, and provides the opportunity for people to voice concerns.

Read more

- Cherney, A. and Murphy, K. (2017). Police and Community Cooperation in Counterterrorism: Evidence and Insights from Australia. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. 40 (12): 1023–1037

- Langley, B., Ariel, B., Tankebe, J., Sutherland, A., Beale, M., Factor, R. and Weinborn, C. (2020). A Simple Checklist, That is All it Takes: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Field Trial on Improving the Treatment of Suspected Terrorists by the Police. Journal of Experimental Criminology. Early Access Article

- Shanaah, S. (2019). Alienation or Cooperation? British Muslims’ Attitudes to and Engagement in Counter-Terrorism and Counter-Extremism, Terrorism and Political Violence. Terrorism and Political Violence. Early Access Article

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)