Introduction

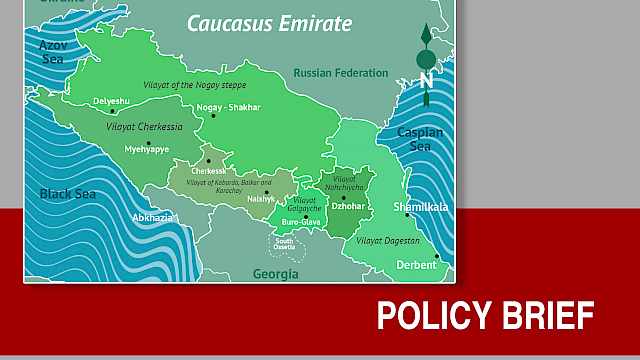

The North Caucasus is the most volatile region in the Russian Federation and has been the setting for violent conflicts including ethnic, religious, and separatist struggles.

The South Caucasus, comprised of the sovereign states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia is geopolitically important to Russia as a southern corridor to the Middle East, and is, in the Russian view, its ‘backyard’. Georgia in particular, with its anti-Russian and pro-Western stance, has been a major flashpoint of contention between Russia and NATO, with an open conflict occurring between the two states in 2008.

Why is the Caucasus important, and what does the Russian deployment of disinformation in the region tell us? The fact that the North Caucasus and Georgia are seen by the Kremlin as areas where it can use, and has used, aggressive military force makes the disinformation deployed there important to understand. In particular, this report illustrates how Russia sees the use of strategic influence in its own neighbourhood.

Beslan

On 1 September 2004, armed Islamic militants occupied a school in the town of Beslan in the Republic of North Ossetia for three days, taking more than 1,100 hostages, of which 777 were children. The hostage-takers, guided by North Caucasus insurgency leader Shamil Basaev, demanded the recognition of Chechnya’s independence and the withdrawal of Russian troops from Chechnya.

On the third day of the crisis, Russian security forces stormed the school with tanks and incendiary weapons. 334 people were killed, including 318 hostages, of which 186 were children.

From the beginning of the siege, the number of hostages was deliberately underestimated by the authorities. Television channels and government representatives repeated that the number of hostages was 354, up until the storming of the school building. This happened even as higher numbers of hostages were reported by some newspapers and Internet sources, as well as Beslan residents on the ground.

From the outset of the hostage crisis, North Ossetia FSB chief Valeri Andreev and others projected blame for the attack on Chechen and international terrorists rather than on the Ingush fighters many locals suspected. This may have been to avoid the potential intensification of inter-ethnic tensions between the Ingush and Ossetians.

The chairman of the Central Spiritual Board of Muslims, a Kremlin-controlled body, Mufti Ravil Gainutdin also laid the blame at the feet of ‘international terrorism leaders.’ At the same time, the authorities took measures to suppress any competing stories that would damage the credibility of the government’s version of events.

Authorities took measures to suppress any competing stories that would damage the credibility of the government’s version of events.

A number of well-known journalists were prevented from travelling to Beslan and after the storming of the school, international journalists from Germany, the US, and Georgia had their video footage seized by local authorities.

The 2008 Georgia-Russia War

The Russo-Georgian war, between Russia, Georgia, and the Russia-supported self-proclaimed republic of South Ossetia, legally a part of Georgia but de facto independent took place in August 2008.

At the time, relations between Russia and Georgia had been worsening. On 1 August, South Ossetian separatists began shelling Georgian villages, with intermittent responses from Georgian peacekeepers.

The Georgian Army entered the conflict zone in South Ossetia on 7 August and took control of the capital of South Ossetia, Tskhinvali the same day. Russian media sources inflated, or at the very least, did not have any basis for the casualty figures, attributable to Georgian assailants, but these figures were picked up by Russian media and repeated, creating part of the justification for intervention.

Before the Georgian military response, Russian troops mercenaries and ‘volunteers’ streamed into Abkhazia and South Ossetia: this was followed by a land, air and sea invasion of Georgia on 8 August.

Information Control

By disseminating television footage and daily interviews with Russian military representatives, Russia was able to control the flow of international information by shaping the conversation and sharing the progress of Russian military actions.

A review of international media during this time shows that Russian President Dmitry Medvedev was perceived as less aggressive than his Georgian counterpart, and a CNN poll conducting during this period found 92 per cent of respondents believed Russia was justified for intervening

Suggesting some level of war planning, Russian state media was ‘extremely well prepared to cover the outbreak of armed conflict in Georgia’ with the main TV channels quickly displaying ‘elaborate graphics’ and ‘news anchors’ adhering to particular pointing points about the causes of the conflict.

The Russian government positioned Russian journalists in Tskhinvali, the capital of the unrecognised Republic of South Ossetia before the start of hostilities.

The day before Georgia introduced its troops into South Ossetia, there were already at least 48 Russian journalists there, and only two accredited foreign journalists.

The day before Georgia introduced its troops into South Ossetia, there were already at least forty-eight Russian journalists there, and only two accredited foreign journalists.

Cyber attacks

Cyber attacks included webpage defacements, denial of service, and distributed denial of service on Georgian government, media, and financial institutions. Overall, citizens were denied access to 54 websites related to communications, finance, and government leading to some speculation about Russian complicity. The Russian government denied the allegations that it was responsible for the attacks.

However, security researcher Greylogic published a report which concluded that Russia’s Foreign Military Intelligence Agency (GRU) and the Federal Security Service (the FSB), not civil hackers, were likely to have played a key role in coordinating and organising the attacks. The Greylogic report concludes that the evidence available strongly suggests GRU/FSB planning and direction at a high level at the same time as it relied on Nashi (a Kremlin-allied youth group) agents as well as crowdsourcing to obfuscate their involvement.

Ramzan Kadyrov and Digital Media

A look at Chechnya’s leader Ramzan Kadyrov and his use of the internet provides a clear example of a Russian political figure using the digital space for a unique combination of disinformation and propaganda. Ramzan Kadyrov is an avid user of social media and was previously best known for his Instagram account, which had more than 3 million followers before it was blocked in late 2017 as a result of US sanctions.

He is now on the Telegram messenger application, which was recently blocked in Russia, but which Kadyrov defiantly continues to use to disseminate his messages.

Information Control

Kadyrov heavy-handedly controls information about the Chechen Republic. All information given by Chechnya’s television, radio, and online news outlets is censored or self-censored to avoid retribution for criticising the authorities. The last groups left to report truthfully from the republic – independent journalists from other parts of Russia (usually Moscow), and human rights organisations, have been threatened and their work impeded by the Chechen security services.

Human rights defenders who were previously numerous in Chechnya have been repressed to the point of all but stopping their work in the republic.

Human rights defenders who were previously numerous in Chechnya have been repressed to the point of all but stopping their work in the republic. After Memorial’s Natalia Estemirova was murdered in 2009, the Chechen government continued to intimidate and discredit the organisation, and the Committee Against Torture’s Mobile Group took over in Chechnya.

By 2014, however, the Mobile Group’s offices had been attacked three times and set on fire and its staff was the target of a smear campaign in the Chechen media. In June 2015, a mob destroyed the office and seized documents related to ongoing cases the Committee was in the process of investigating. The Mobile Group ceased its permanent residence in the republic in 2016.

Kadyrov is attempting to halt the diversification of public debate in the republic, brought on by both human rights workers and lawyers, but also by citizens on social media. Kadyrov sees the digital space as a place people can sidestep traditional media as a state-controlled controlled entity that reports only the official viewpoint of the state. While Kadyrov does not engage in Internet shutdowns of networks as other authoritarian leaders have done his actions still represent those of a rational autocratic actor whose primary goal is to stay in power.

Conclusion

What do these cases tell us? Firstly, this tells us that there is no playbook by which the Russian authorities use for disinformation campaigns. During the Beslan siege, the disinformation was mostly reactive, highlighting the unpreparedness of the Russian authorities and constituting a series of responses to control the framing of extremely fluid and unpredictable events as they developed.

In the aftermath of the school storming, confronted with emerging discourses about the incompetence of the Russian government’s handling of the events, Putin blamed an international conspiracy and characterised Russia as a ‘besieged fortress’, which served as justification for paring down on civil liberties and strengthening censorship of media across Russia.

Secondly, these cases show that Russian disinformation campaigns are not managed in a strictly top-down manner. Rather, lower-ranking government officials can voluntarily pick up and repeat the specific government talking points, as do various actors in society such as the media and bloggers.

These cases show that Russian disinformation campaigns are not managed in a strictly top-down manner.

Lastly, these cases tell us that different Russian institutions are involved in each case of disinformation. In Kadyrov’s case, you have a disinformation and propaganda project that is completely separate from the Kremlin, even as it is used to support the Kremlin and Putin in particular. Thus, Kadyrov’s disinformation project is one that can be said to be to primarily influence Putin, to convince him of Kadyrov’s loyalty and suitability for his post, and to show how the republic is developing. Disinformation in the form of cyberattacks is also almost always attributable to the GRU, which, for example, had almost no role in the Beslan siege.

The Russian authorities often base their disinformation on the masking of real identities (plausible deniability), meaning that perpetrators can remain unidentified. A similar process has been enabled by the emergence of computer technologies – as proxy servers, infected computers, spyware and viruses are used to compromise the online information space. Very similar principles underpin aspects of disinformation as deployed physically, in the North Caucasus, as this report demonstrated.

Copyright Information

As part of CREST’s commitment to open access research, this text is available under a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence. Please refer to our Copyright page for full details.

IMAGE CREDITS: Copyright ©2024 R. Stevens / CREST (CC BY-SA 4.0)